‘Resting’ autism brains still hum with activity

Even at rest, the brains of people with autism manage more information than those of their peers, according to a new study that may provide support for the so-called ‘intense world’ theory of autism.

Even at rest, the brains of people with autism manage more information than those of their peers, according to a new study that may provide support for the so-called ‘intense world’ theory of autism.

The research, which was published 24 December in Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, included nine children with Asperger syndrome, aged between 6 and 14 and ten age-matched typical children. The researchers scanned their brains using magnetoencephalography (MEG), a noninvasive method that doesn’t require lying in a noisy, confined space as magnetic resonance imaging does.

That method was important for this study because the researchers wanted to capture the brain’s activity when it was receiving as little external stimulation as possible. During the data collection, the children were in a magnetically shielded room, with the MEG recording device over their heads.

The children had to lie still with their eyes open. That raises the question of whether their brains were actually at rest — but Galan says even if the children weren’t completely without external stimulation, the results suggest that in the same boring situation, people with autism process more information than their typical peers.

“Our results fit very well with the intense world theory, which describes autism as a disorder resulting from hyperfunctioning neural circuitry, which leads to a state of over-arousal,” says lead researcher Roberto Galan, assistant professor of neuroscience at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio.

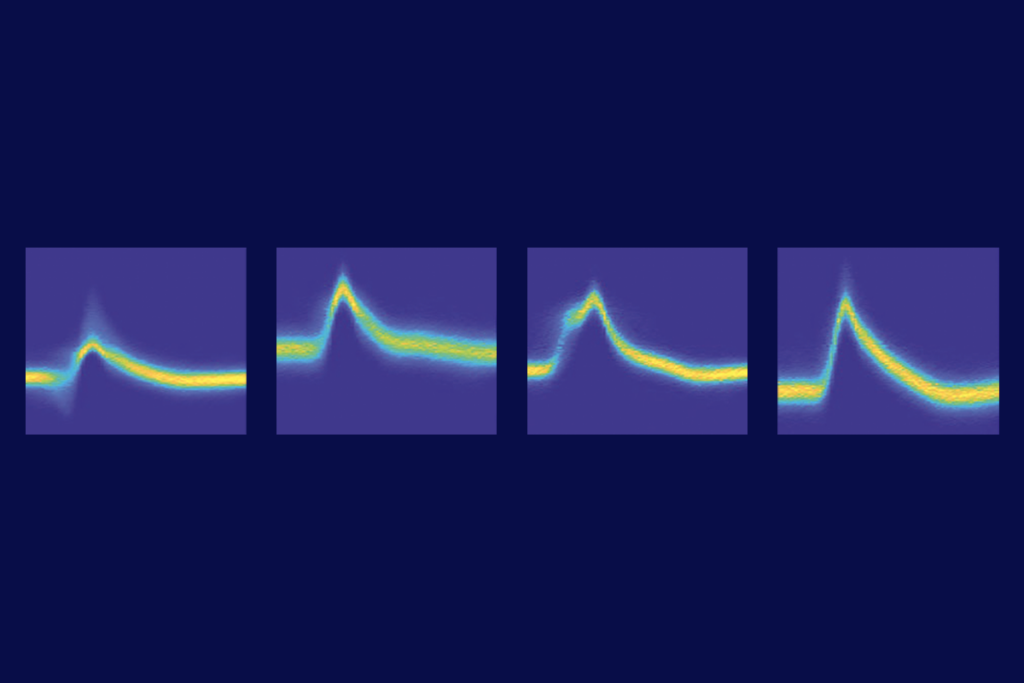

‘Information’ is defined scientifically as the level of mathematical complexity of a signal, Galan says. Using a computational model, the study found that under the same conditions, the children with autism on average showed a 42 percent higher information gain than the controls did.

Samuel Schwarzkopf, a research fellow in cognitive, perceptual and brain sciences at University College London, questions whether the results indicate more intense sensory perception from outside — supporting the intense world theory — or indicate that the brains of the children with autism internally generate more information. “I think [Galan’s] main interpretation is highly speculative,” Schwarzkopf says.

Schwarzkopf has a study in the 12 February issue of The Journal of Neuroscience that offers only partial support for the intense world view. Using functional MRI on 15 adults with Asperger syndrome and 12 age-matched controls, he and his colleagues found that the visual cortex of the participants with autism responds more strongly to visual stimulation than that of controls do, which could make their sensory experience more intense.

However, the study did not find better visual perception in participants with autism than in controls, questioning the hypothesis that a superior ability to detect small differences is what creates an overly intense experience of the world.

Recommended reading

INSAR takes ‘intentional break’ from annual summer webinar series

Dosage of X or Y chromosome relates to distinct outcomes; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Null and Noteworthy: Neurons tracking sequences don’t fire in order