In May, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. expressed interest in expanding access to experimental therapies, including stem cells, during a podcast interview. He also acknowledged that he has received unproven stem cell treatment in Antigua. These comments, taken with his broader interest in autism and enthusiasm for alternative medicines, are signals that we could soon see the U.S. Food and Drug Administration soften its oversight of the stem-cells-for-autism space.

As a stem cell biologist, I’m excited about the potential of stem cell therapies for many conditions. Recent solid clinical trial data on their use in Parkinson’s, type 1 diabetes and epilepsy are three examples of encouraging early outcomes.

But despite much hype, cell therapies are not a panacea. In the specific case of autism, I don’t believe that infusions of cells, such as adipose or bone marrow stem cells or umbilical cord cells, are promising approaches. Numerous teams have tested these cells, and yet there is still no evidence that these treatments help people with the condition.

In fact, one of the largest trials testing cord blood to treat autism, led by Duke University, missed its endpoints. More recently the Duke team’s partnership with Cryo-Cell International, a company that banks cord cells, collapsed. That breakup is a warning sign, suggesting this research is unlikely to prove fruitful in the future. A similar earlier trial of cord cells for autism by Sutter Health also missed its endpoint.

Both the Duke and Sutter researchers conducted post-hoc analyses and made statements about possible benefits to subgroups, but these claims were unconvincing to me. Beyond cord cells, I have not seen any encouraging data from trials of stem cells for autism more generally.

I

f the data are generally negative, why has this field continued to garner so much attention? Most of the outright hype comes from clinics doing a hard sell of unproven cell infusions to generate profits.Whether it’s umbilical cord, fat, bone marrow or other kinds of cells—even if those cells are not truly stem cells—the marketing has been relentless. In my view, some academics around the world have also overstated the promise of cell therapies for autism, but I believe in such cases this results more from overexuberance.

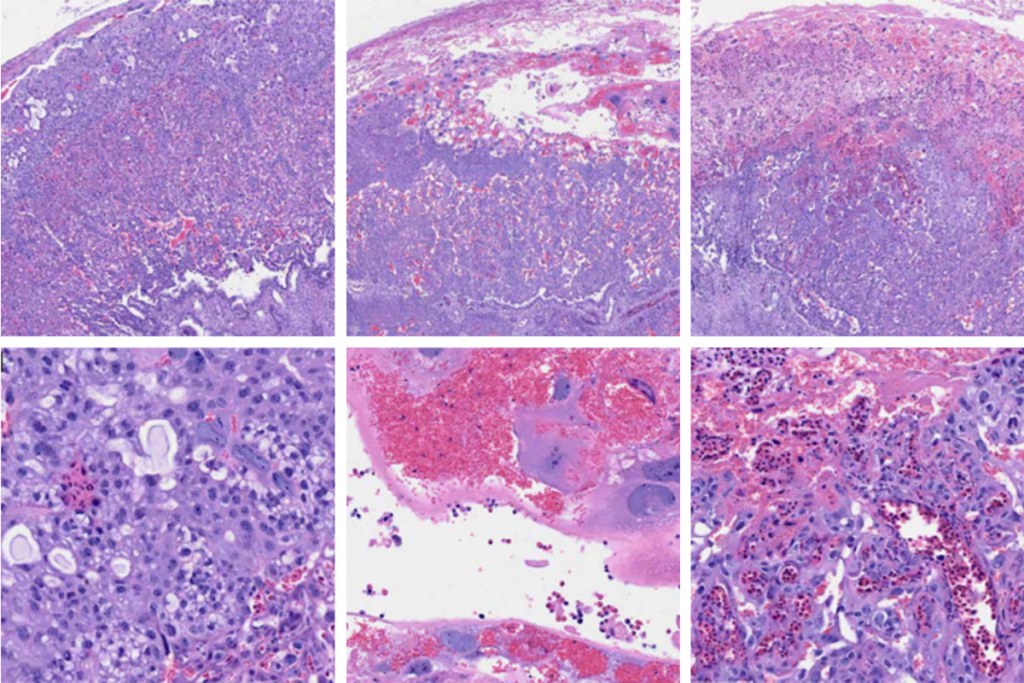

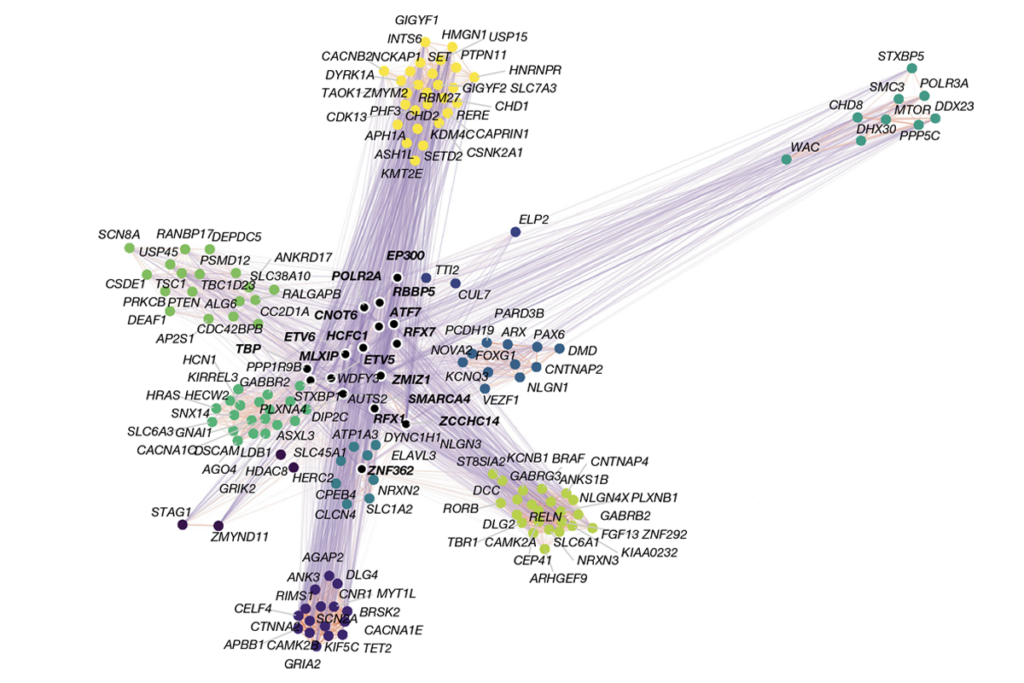

Autism is a challenging target for these therapies. The condition is famously heterogeneous. A recent genetic study defined four potential autism subgroups, and there are probably more. Autism’s mechanisms are therefore many and varied, making it harder to treat with a single therapy, and trial outcomes are likely to have quite a lot of noise.

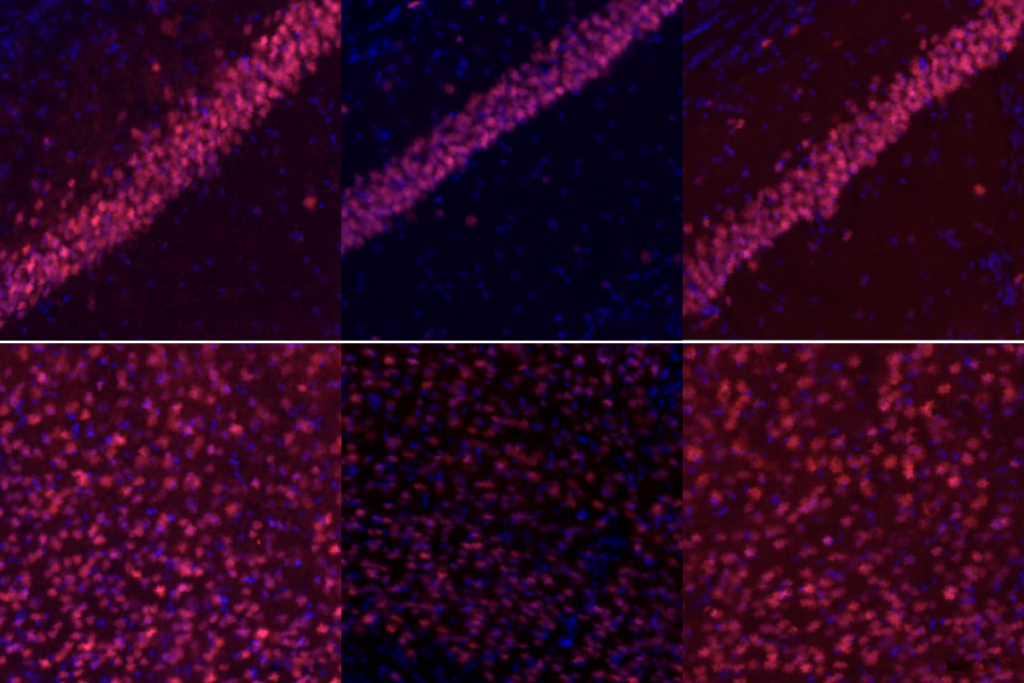

Proponents of cell therapies for autism have put forward many different explanations about how these treatments might work. For example, they have cited the hypothesis that infused cells repair neurons directly inside the brain. But as it has become less clear whether infused cells can even reach the brain in meaningful numbers, supporters have instead invoked vague, indirect immunomodulatory functions as possible mechanisms.

The idea of stem cells for autism also contributes to a controversial cure narrative about the condition. This narrative portrays autism as a disease and the people who have it as needing “fixing” somehow. This perspective can also negatively affect those with autism and their families.

A

s a biomedical researcher, I think it’s critical for clinicians and scientists to become informed so that we can speak to the public about these issues. I believe thousands of families have gotten the wrong idea about the promise of stem cells for autism.Many hundreds have had their children infused with umbilical cord cells through clinical trials, expanded-access programs and for-profit clinics. Although umbilical cord cells seem generally safe, they are not entirely risk free. Plus, the experience of pursuing these treatments (including travel to the clinic and sedation for the procedure, which is commonly used) can negatively affect children. Some trials charge people to participate—a practice that is unacceptable in my view.

For these reasons it’s important for scientists and clinicians to do educational outreach in this area. We also need to push back on the sometimes market-driven hype about stem cells for autism.

In the United States, the FDA has had real trouble keeping up with clinics selling such things. Clinic firms often market cells for autism and for many other, unrelated conditions, perhaps to maximize profits. When one clinic gets in hot water and disappears, a new one takes its place. It’s been a never-ending game of stem cell whack-a-mole.

Looking ahead, autism cell therapy clinical trials keep popping up, but I don’t expect them to go anywhere productive. I hope to be proven wrong, but so far there’s little reason for optimism. In a search for active, interventional trials with the words “cells” and “autism” on ClinicalTrials.gov (which, importantly, does not necessarily indicate whether these are traditional, robust clinical trials), I find 68 listings. Just ten are recruiting.

None appear particularly promising. Still, one caught my eye: a Caribbean trial listing by orthopedic surgeon Chadwick Prodromos, of the Prodromos Stem Cell Institute, who has multiple stem cell clinics in the U.S. and elsewhere. Prodromos recently told me in an interview that he was the physician who gave Robert F. Kennedy Jr. stem cells for his throat condition in Antigua. He also attended a Kennedy roundtable on regenerative medicine in March.

It’s definitely not the time to loosen stem cell therapy standards. Particularly with all the discouraging data out there already, pushing harder on the idea of stem cells for autism just doesn’t make sense now. I urge special caution for families considering paying for this kind of intervention for their kids. It’s likely to do more harm than any good—if it does anything at all.