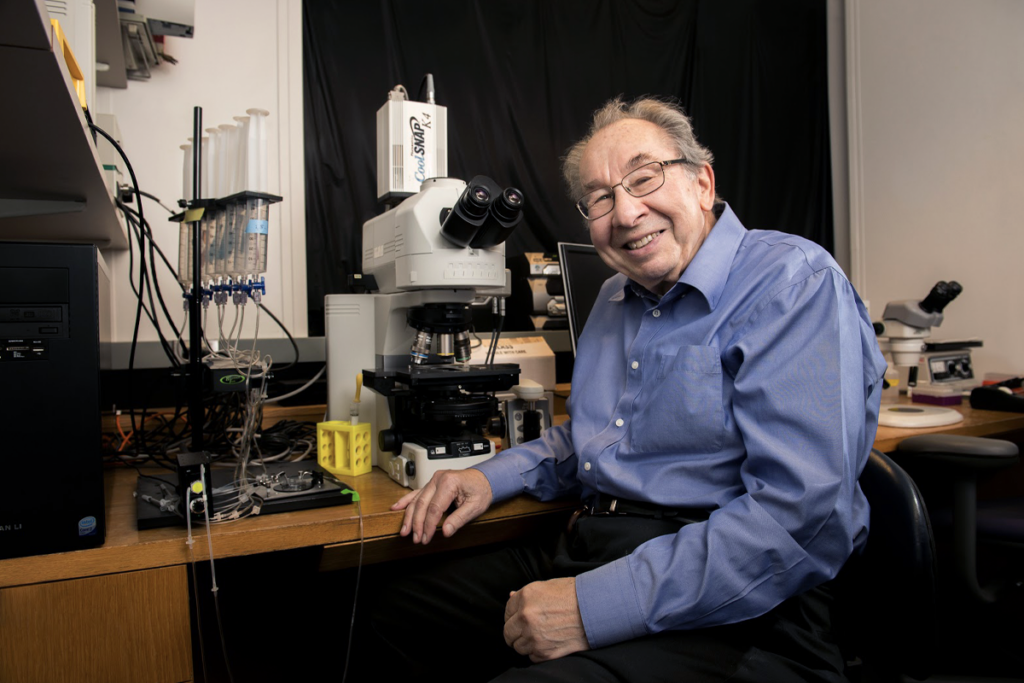

Remembering Adam Kampff, neuroscience educator and researcher

Kampff’s do-it-yourself approach inspired a generation of neuroscientists.

On a trip to Munich in 2004, Adam Kampff, then a Harvard University graduate student, stopped to visit with Tom Mrsic-Flogel, who was doing a postdoctoral fellowship at the Max Planck Institute of Neurobiology. The two had first met when they roomed in the same house during the Society for Neuroscience conference in New Orleans the year before.

Kampff found Mrsic-Flogel stymied by a broken two-photon microscope, and for the next several weeks they worked on fixing it. At night, they went out for beer and Bavarian pretzels with butter, recalls Mrsic-Flogel, now director of the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre at University College London.

This kind of assistance, Mrsic-Flogel says, was typical of Kampff, who died of cancer on 9 December at age 45. Kampff ran his own laboratories in London and Portugal, where he led the team that developed Bonsai, a programming framework to handle multiple streams of experimental data. But his career was also marked by his efforts to help other researchers, including launching No Black Boxes, a project that trains people on how to use new technologies.

“I don’t think you can measure his impact the way you would for traditional scientists,” says Bence Ölveczky, professor of organismic and evolutionary biology at Harvard, who supervised Kampff’s postdoctoral research. “Most of us are trying to claw ahead in this game of academia. And he was not interested in it. He wanted to just teach and share his wisdom generously.”

R

That year, Kampff joined the newly formed lab of Florian Engert and—using what he had learned about optics from his astronomy training—constructed a prototype for the team’s first two-photon microscope. When he became a doctoral student in the lab, he tackled a logistical problem: Engert was curious about what larval zebrafish could offer the systems neuroscience field, but most research equipment was built for cell cultures and rodents. Kampff developed the team’s custom experimental setups, paving the way for the lab to visualize brain-wide activity in the fish.

“He basically single-handedly built my lab,” Engert says. While at Harvard, Kampff also met his first wife, Eva Naumann, now assistant professor of neurobiology at Duke University.

Kampff’s refusal to be held back by technological limitations rubbed off on Kristen Severi, assistant professor of biological sciences at the New Jersey Institute of Technology, who was a fellow doctoral student in Engert’s lab. “That absolutely flipped my worldview,” she says. “We can just write the code. We can just build the microscope.”

Kampff carried this mindset to his postdoctoral research on the role of the motor cortex in motor learning and control at Harvard, supervised by Ölveczky, who describes him as a “joker in the pack” but also a researcher who transformed the lab by inspiring his colleagues to tackle problems in new ways.

After his postdoc, Kampff started a lab at the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown, a research institute in Lisbon, Portugal. There, his team created the Bonsai framework, which allows video-tracking and electrical physiology data, among other data types, to be collected during closed-loop behavioral experiments and today is used by teams at the Allen Institute, Columbia University and elsewhere.

Rui Costa, president and chief executive officer of the Allen Institute, who was research director at Champalimaud at the time, says that during this period, the institution began asking group leaders during presentations who had influenced their work. So many mentioned Kampff, Costa says, that leadership at Champalimaud began to call this the “Adam factor.”

Kampff’s first marriage ended during this time, and while at a conference, he was introduced to zebrafish researcher Elena Dreosti, who also needed help building a two-photon microscope. They ended up marrying in 2016 and eventually had two children. Together they went to the United Kingdom, where Kampff set up one of the first neuroscience research groups at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre.

B

Kampff prioritized spreading scientific knowledge over publishing flashy papers in prestigious journals, Engert says. “His footprint on science was absolutely remarkable, and it just doesn’t show up in author lists.”

Kampff also left his mark as a teacher. Severi says his guidance in the lab informed her own mentorship of students. “There isn’t a time that goes by that I don’t think, ‘Oh, this is something that Adam taught me. I should teach them that.’”

Kampff leveraged that skill in 2012, when he and his former Harvard colleague Florin Albeanu, now professor at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, and Raul C. Mureşan of the Transylvanian Institute of Neuroscience in Romania, co-founded the Transylvanian Experimental Neuroscience Summer School.

The program taught students that they can “build top-notch equipment without much infrastructure if they have the people around them that actually have expertise,” Albeanu says. “The spirit of the school is very much Adam’s spirit.”

Kampff was also working on another entrepreneurial idea. In 2010, he began to develop training materials to help Ph.D. and other graduate students understand new technologies. The project would become No Black Boxes.

In 2020, Kampff left his research post at the Sainsbury Wellcome Centre (though he continued to teach a graduate neuroscience boot camp), and he and Dreosti broadly launched No Black Boxes the next year. This effort included NeuroKit, a package of supplies for an online course that teaches neuroscientists how to build a robot, which made instruction possible during the COVID-19 pandemic. No Black Boxes also offers instruction for scientists in other disciplines, as well as courses for secondary school students, which were inspired, Dreosti says, by their two young children, who were curious about the smartphones and remote controls they saw around the house. Dreosti says there are plans to start an official foundation to support the initiative.

As Kampff’s condition worsened in his final weeks, Engert, Ӧlveczky and Mrsic-Flogel visited him in the hospital. Mrsic-Flogel bore Bavarian pretzels and cold butter, at Kampff’s request, to remember their time in Munich. “We found him a really good bakery here and brought them back, and we enjoyed it so much,” Mrsic-Flogel says. “These moments, very little things matter.”

Recommended reading

Cracking the neural code for emotional states

Neuroscience needs engineers—for more reasons than you think

The challenge of defining a neural population

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering GABA pioneer Edward Kravitz

Remembering Mark Hallett, leader in transcranial magnetic stimulation