Neuroscience has a species problem

If our field is serious about building general principles of brain function, cross-species dialogue must become a core organizing principle rather than an afterthought.

Neuroscience has never been richer in data. Laboratories now generate detailed recordings of neural activity, behavior and physiology across species at scales unimaginable a decade ago. In rodents, researchers can monitor thousands of neurons simultaneously across distributed circuits during behavior. In humans, they can record from deep brain structures during ambulatory, real-world behavior, integrated with wearable sensors and linked to clinical symptoms and subjective experience. The field has access to neural signals spanning orders of magnitude in space, time and biological complexity.

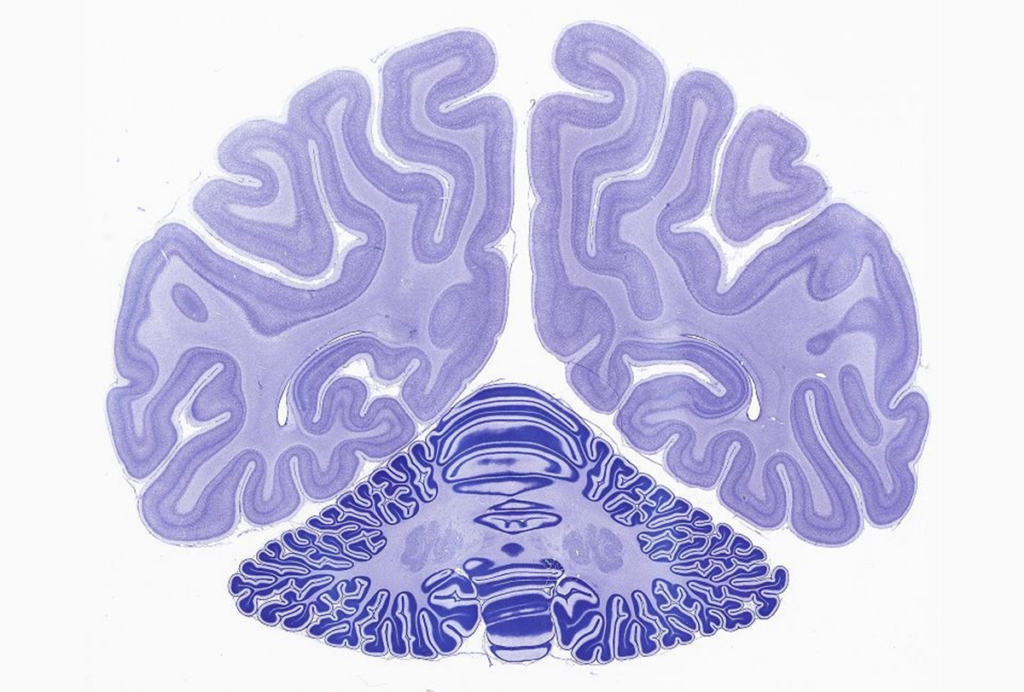

Yet despite this abundance, neuroscience remains deeply organized along species lines. Animal and human researchers often operate within separate conceptual frameworks, attend different conferences and develop theories that rarely confront data across species. This separation is no longer a minor inconvenience but a growing liability. The problem is not simply that cross-species translation is difficult; it is that the field has largely accepted this difficulty rather than treating it as a central scientific challenge. Neuroscience has also struggled to confront the fact that different species often tell different stories.

As a result, neuroscience’s primary limitation today is not a lack of data or tools, but persistent fragmentation across model systems, recording modalities and analytic traditions. Findings are typically interpreted within species- and technique-specific frameworks, with little pressure to explain when, how or why neural principles should generalize across organisms. Researchers acknowledge differences but rarely use them to constrain or revise theory.

If neuroscience is serious about building general principles of brain function, cross-species dialogue must become a core organizing principle rather than an afterthought. Differences between species should be treated as informative constraints that refine theory, not as inconsistencies to be explained away. Overcoming this divide won’t be trivial, but there are ways we can start now to begin to change our culture.

A

These boundaries persist across species, even as many of the technological constraints that once justified them have faded. As a researcher studying the human brain using both single-unit and local field potential recordings, I am acutely aware that these signals offer distinct and complementary views of neural activity, each with its own strengths and limitations. In humans, it’s now possible to directly record brain activity during behaviors such as walking and natural navigation, enabling experiments similar to those in animals. Single-unit sampling in humans is sparse, however, so field potentials are often the primary signal available for linking neural activity to ethologically relevant behavior.

High-density single-unit recordings in animal models are therefore essential for understanding how population-level signals relate to single-neuron activity. Yet even when spikes and field potentials are recorded simultaneously in animal studies, researchers often prioritize single-unit analyses, reflecting long-standing theoretical preferences. These preferences limit opportunities to connect neural activity across scales and species. Rather than optimizing theories around a single signal or model organism, the field would benefit from frameworks designed to link signals across scales, using the strengths of each system to offset the limitations of others.

Theta oscillations, a brain rhythm typically defined as 4 to 8 hertz, provide a clear example of how this fragmentation plays out in practice. The details of theta matter less here than what its cross-species differences reveal about how the field handles disagreement. In rodents, hippocampal theta activity during locomotion appears to be largely continuous, a regularity that has shaped decades of influential models of navigation, memory encoding and temporal organization. In humans, however, hippocampal theta activity occurs in brief, intermittent bouts, often linked to specific behavioral or cognitive events rather than ongoing movement. These findings have been replicated across laboratories and tasks and are supported by converging evidence from bats and nonhuman primates.

When these findings emerged, they were initially met with skepticism. Rather than asking what the differences might imply for theory, the dominant response was to question whether the signals were truly comparable. As evidence accumulated over time, skepticism softened. But theories that attempt to meaningfully integrate the two types of theta are still largely lacking.

Nearly a decade later, rodent-derived models continue to assume sustained oscillatory structure, although bat, nonhuman primate and human findings are treated as species-specific implementation details rather than as constraints on general principles. For the most part, scientists have not tried to uncover why different species recruit theta in distinct ways, what computational roles these patterns serve, or whether continuous and intermittent theta reflect complementary solutions to shared navigational and memory demands, or distinct modes of environmental sampling, such as whisking, echolocation or eye movements.

T

Yet these differences are precisely where theoretical progress should occur. Intermittent hippocampal theta suggests a fundamentally different mode of coordinating neural activity, one in which rhythmic structure is recruited transiently to gate information, mark boundaries between events, or coordinate distributed circuits at specific moments rather than continuously. Ignoring these implications does not preserve existing theories; it limits their scope and explanatory power.

Cultural asymmetries within the field reinforce this divide, a pattern I observe as a researcher who studies the human brain. When human data align with animal model data, they are welcomed as validation. When they do not, they face higher evidentiary thresholds and greater skepticism. This skepticism is often justified by appeals to sample size, even though nonhuman primate studies, long viewed as theoretically foundational, have historically relied on similarly small cohorts. Such asymmetries insulate animal-derived theories from challenge and weaken the role of human research as a source of theoretical insight rather than mere applied confirmation.

For much of my career, I have watched this divide only perpetuate and deepen. I have attended conferences where animal research overwhelmingly shaped the agenda and human work was treated as secondary. At human-focused meetings, the reverse was true, with few researchers whose primary work involved non-primate species having influence over the event. These experiences shape not only which conversations happen but which questions young scientists learn to ask. The result has been the emergence of parallel scientific cultures that rarely engage deeply with each other.

Overcoming this divide, and developing theories that incorporate contrasting data, will require shifts in how scientists are trained, how conferences are structured and how cross-species work is valued within academic culture. It will also require theoretical frameworks and models that are explicitly tested and revised across species rather than optimized within a single model system. Finally, funding, review and publication practices must reward work that treats cross-species differences as opportunities for insight rather than liabilities to be minimized.

AI use disclosure

Recommended reading

Nonhuman primate research to lose federal funding at major European facility

NIH proposal sows concerns over future of animal research, unnecessary costs

Star-responsive neurons steer moths’ long-distance migration

Explore more from The Transmitter

Seeing the world as animals do: How to leverage generative AI for ecological neuroscience

Beyond the algorithmic oracle: Rethinking machine learning in behavioral neuroscience