Betting blind on AI and the scientific mind

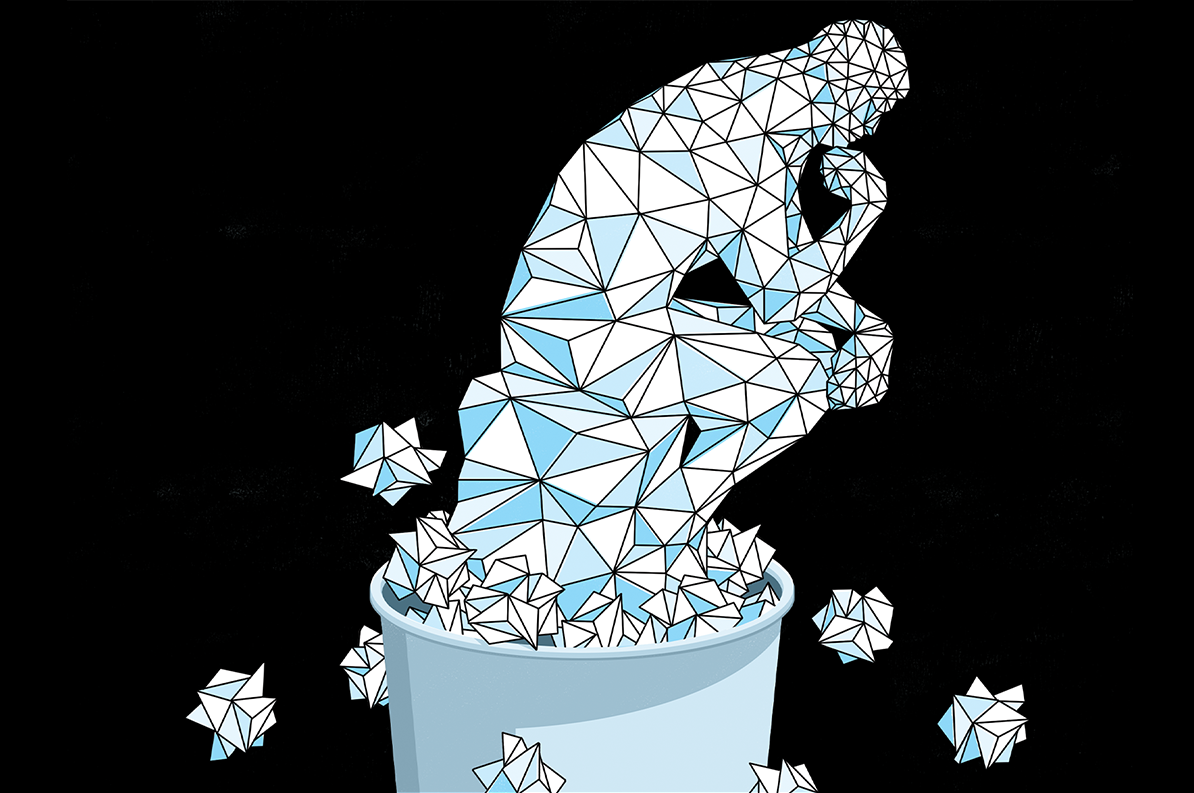

If the struggle to articulate an idea is part of how you come to understand it, then tools that bypass that struggle might degrade your capacity for the kind of thinking that matters most for actual discovery.

A few weeks ago, I sat in a faculty meeting about artificial-intelligence policy for our graduate students. After three years of drafting guidelines, revising them and watching them become obsolete, we were debating whether to ban AI use for thesis proposals and dissertations, despite the technical impossibility of enforcing a ban. One colleague cited an MIT Media Lab study that had gone viral over the summer, showing reduced neural connectivity in people who wrote with ChatGPT. “Cognitive debt,” the researchers called it. The study has real limitations, but it crystallized a worry that has been building since ChatGPT’s launch. If writing is a form of thinking, if the struggle to articulate an idea is part of how you come to understand it, then tools that bypass that struggle might degrade a scientist’s capacity for the kind of thinking that matters most for actual discovery.

I’ve been thinking about AI and scientific writing for a while now, and I find myself caught between two positions I can’t fully accept. The worry of “cognitive debt,” or skill decay, or however you want to frame the general issue, feels legitimate to me. But so does the counterargument that these worries are overblown. And the more I’ve looked for evidence that might settle the question, the more I’ve come to believe that the evidence doesn’t exist—at least not for the population actually practicing science.

Anyone who writes seriously will recognize how useful writing can be in the thinking process. You’re working on an aims page that seemed clear in your head, but it’s just not working when you try to write it down. The logic that felt sturdy in your mind keeps crumbling on the page. You rearrange, and now something else breaks. After an hour of struggle, you realize that what felt like a communication problem is turning out to be a thinking problem, one you couldn’t see until the writing forced you to confront it. The writing-as-thinking assertion has many proponents—whom we might call in this context the “cognitive traditionalists.” As the writer Flannery O’Connor memorably put it: “I write because I don’t know what I think until I read what I say.” Or as Richard Feynman said of his notebooks: “They aren’t a record of my thinking process. They are my thinking process.”

I

The question is whether the loss of unassisted writing actually matters to science. Here, so-called “AI apologists” have arguments on their side. The first is that writing isn’t so precious as the traditionalists make it out to be. Any cognitive benefit might not be about writing per se, but about externalization—the act of forcing internal representations into some external form where they can be inspected, challenged, revised. If that’s the mechanism, then dialogue might work as well as solitary composition. Talking through your ideas with a colleague, defending your approach at a lab meeting, explaining your project to a collaborator from another field—these are also scenarios where vague intuitions get stress-tested, where gaps become visible, where you discover what you actually think. Psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky famously took long walks together to spark ideas that led to their Nobel Prize-winning work in behavioral economics. And if externalization is what matters, some might argue that even dialogue with an appropriate AI system might preserve the cognitive benefit. You’re still articulating. You’re still making implicit reasoning explicit. The medium changed, but perhaps the mechanism remains intact—implying that, for science, enough useful cognition can occur outside of writing that offloading writing won’t be as impactful as the cognitive traditionalists suggest.

The AI apologists have data on their side, at least of a certain kind. A study published last month in Science found that researchers who adopted large language models started posting one-third to one-half more papers, with the largest gains among non-native English speakers. This is not nothing. The barriers that non-native speakers face are real and well documented; if AI can lower them, that’s a genuine benefit for equity in science. These data, however, may provide strong evidence for equity in the professional markers of scientific progress but say nothing about the quality of the underlying science. Indeed, many scientists have raised alarms that AI will merely accelerate the production of papers while doing nothing to address the actual bottlenecks that slow genuine scientific progress.

S

Which leaves us with the advice to “use AI responsibly.” Offload the needless struggle, but preserve the useful cognitive work. On the surface, this is a reasonable stance. One that I, whom you might call an AI pragmatist, even took myself. But the AI pragmatists presuppose specific metacognitive abilities: Can writers learn to recognize, in the moment, whether a particular difficulty is productive versus merely frustrating?

I was once hopeful, but I have since concluded I don’t think writers can make that call, at least not consistently. Research on metacognition suggests that our intuitions about our own learning are not just unreliable but actively misleading. Education researchers use the term “desirable difficulties” to describe conditions that feel harder but produce better learning, as opposed to conditions that feel like learning but don’t actually produce it. The problem is that people can’t reliably tell the difference, and in fact they usually prefer conditions that merely feel like learning. Students report learning more from polished lectures than from active participation, even though the research shows the opposite. Participants trained to identify painters’ styles performed dramatically better with interleaved practice, but 78 percent said blocked practice had worked as well or better. In one classic study, postal workers whose training was spread out over time performed better but reported less satisfaction than those whose training was concentrated into fewer, longer sessions. We not only mistake the feeling of learning for actual learning, but we mistake signs of struggle as signs of not learning.

Let’s return to that stubborn aims page. When your aims page isn’t coming together, the struggle might mean you’re tired. It might mean you know what you want to say but can’t find the right words. Or it might mean you don’t actually know what you’re trying to say—that there’s a gap in your reasoning you haven’t confronted yet. In this last case, useful cognitive work happens, yet all three feel the same in the moment: frustration, effort, the sentence that won’t come right. Humans tend to dislike frustration and effort. And worse, effort often doesn’t feel like learning or deepening understanding. This is largely the reason I’ve concluded that metacognitive monitoring is impossible: You can classify struggle retrospectively, by whether insight emerged. You can’t classify it prospectively, which is when you need to decide whether to reach for AI.

A seasoned scientist might object that expertise confers special metacognitive abilities, but I disagree. The problem isn’t inexperience with the domain—it’s the nature of metacognition itself. Being an expert neuroscientist doesn’t make you an expert at perceiving your own cognitive states. I’ve been writing professionally for 15 years, and I’ve been fooled repeatedly. The problem, at this point, isn’t that AI writes badly. It’s not brilliant, and I wouldn’t rely on it for work I care about, but it writes well enough for many purposes, and fast enough that when I do use it, I stop noticing what I’ve skipped. A paragraph appears, it’s serviceable, and I move on. Only later—sometimes much later—do I realize I never worked through what I actually thought. The writing got done. The thinking didn’t.

An obvious fix is to redesign the tools. I was recently introduced to the concept of “cognitive forcing strategies,” which originated 20 years ago in medical decision-making, when an emergency physician proposed that clinicians could use deliberate metacognitive interventions to interrupt cognitive biases that lead to diagnostic errors. In 2021, researchers at Harvard University applied this framework to AI-assisted decision-making, testing interface designs that reintroduce friction. One required users to commit to an answer before seeing AI’s suggestion. Another imposed a delay before revealing recommendations. These designs reduced overreliance on AI, not by helping users perceive which struggles were productive but by creating conditions that tend to help regardless of perception. The catch: People hated them. They rated the most effective designs least favorably and performed best in the conditions they liked least. Any tool that preserves productive struggle will probably lose in the marketplace to tools that eliminate it.

So what to do with a problem that can’t be reliably perceived, is difficult to study and won’t be solved by the marketplace? Science still has a powerful tool, stemming from the fact that it is practiced in communities, and communities can hold expectations that individuals acting alone cannot sustain. I’m talking about norms, and here are three reasonable ones I would start with:

- Protect the training period. Even without knowing which struggles matter most, it’s reasonable to make a conservative bet that more of them matter early on. Things like first grants, first papers and qualifying exams are worth protecting, not because AI assistance is certainly harmful but because the stakes of being wrong are too high.

- Modify AI tools with friction built in. Don’t rely on individual willpower. Build scientist-tailored tools with design choices such as forcing functions built in, and establish norms and incentives to use them.

- Normalize talking about AI in a way that acknowledges its complexity. Right now there’s stigma in both directions—shame about using AI, judgment about refusing it. If people in labs and departments talked openly about what they’re offloading and what they’re protecting, the scientific community might collectively develop better intuitions faster.

We did vote in that faculty meeting. We decided to prohibit AI for thesis proposals and dissertations—knowing it’s essentially unenforceable. The point wasn’t policing. It was signaling: Our graduate program believes this kind of cognitive labor is valuable, and we want students to do it themselves at least once before they start offloading. Cultural norms are strong, even when rules are weak. It’s not a solution. It’s a bet—made with humility about what we don’t know, and with seriousness about what we might lose.

AI use statement

Recommended reading

Seeing the world as animals do: How to leverage generative AI for ecological neuroscience

Neuroscience needs single-synapse studies

Explore more from The Transmitter

From bench to bot: Why AI-powered writing may not deliver on its promise

AI-assisted coding: 10 simple rules to maintain scientific rigor