A new commentary calls into question a 2024 paper that described a universal pattern of cortical brain oscillations. But that team has provided a more expansive analysis in response and stands by its original conclusions. Both articles were published today in “Matters Arising” in Nature Neuroscience.

Ultimately, the back-and-forth suggests that a frequency “motif” may exist, but it may not be as general as the original study proposed, says Aitor Morales-Gregorio, a postdoctoral researcher at Charles University, who was not involved with any of the work. “The [2024] conclusions are way too optimistic about how general and how universal this principle might be.”

The 2024 study identified a brain-wave motif in 14 cortical areas in macaques: Alpha and beta rhythms predominated in the deeper layers, whereas gamma bands appeared in the more superficial layers. Because this motif also showed up in marmosets and humans, the researchers speculated that it may be a universal mechanism for cortical computation in primates.

“Results typically come with a level of variability, of noise, of uncertainty,” says 2024 study investigator Diego Mendoza-Halliday, assistant professor of neuroscience at the University of Pittsburgh. But this pattern “was just there the whole time, at all times, in many, many of the recordings.” The team leveraged the findings to create an algorithm that detects Layer 4 of the cortex.

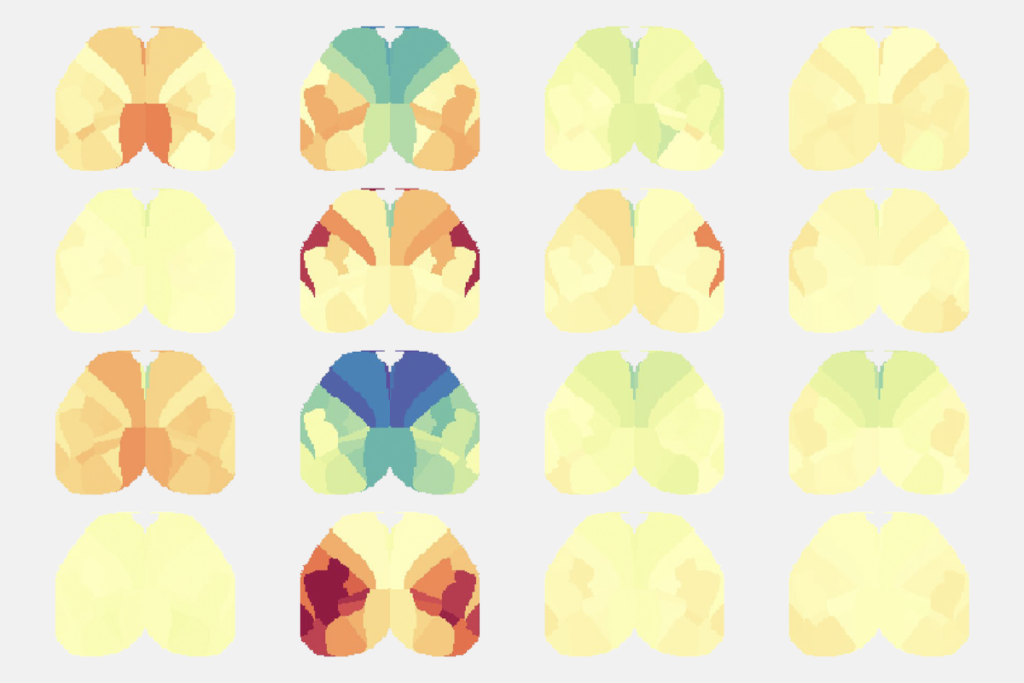

But the pattern is “by no means universal,” according to the new commentary, which found the motif in about 60 percent of the recordings in an independent monkey dataset. Further, the algorithm trained to identify Layer 4 of the cortex is unreliable, the commentary shows.

In response, Mendoza-Halliday and his collaborators expanded their analysis to additional brain regions. And they improved their algorithm’s ability to discriminate between a true motif and noise patterns.

They also point out that many labs have already replicated their 2024 results and used that algorithm successfully. (The study has been cited 85 times.) “Our discovery now stands on even stronger grounds than before,” says study investigator Andre Bastos, assistant professor of psychology at Vanderbilt University.

Although the new commentary prompted the 2024 authors “to create a new version of [the algorithm] that has less of a multiple comparisons problem,” says Chase Mackey, research scientist in Charles Schroeder’s lab at the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research and an investigator on the new commentary, “the original paper remains unchanged; and the original, flawed results are actively being promoted.”

T

Because Layer 4 receives and processes incoming sensory information before distributing it to other cortical layers, it has been an important area of study, Morales-Gregorio says.

But identifying Layer 4 has been a long-term problem in the field, he adds. Typically, researchers identify it by placing a probe into the brain and using an approach called current source density. However, this approach is limited because it relies on sensory responses and is highly sensitive to noise and electrode angle.

The algorithm described in the 2024 study, called frequency-based layer identification procedure (FLIP), uses the shift in brain oscillation frequencies to identify Layer 4 in sensory areas and higher-order cortical areas that are less dependent on sensory input. FLIP was able to identify the motif, and therefore Layer 4, in 64 percent of their recordings, the team found.

In the new commentary, though, FLIP failed to identify Layer 4 reliably and consistently, identifying it 40 percent of the time in the auditory belt cortex, 32 percent of the time in the primary auditory cortex, and only 8 percent of the time in the visual cortex.

The neural activity in the cortex “should not produce a ubiquitous motif. It should produce diversity rather than uniformity,” says Schroeder, director of the Translational Neuroscience Laboratories at the Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research and an investigator on the new commentary. “We went through the whole process as carefully and clearly and transparently as possible, and what we found was that Layer 4 was misidentified in the majority of cases,” he adds. “The estimation of Layer 4, in most cases, was displaced towards the deep layers.”

This discrepancy might be due to differences in the “ground truth” that both groups use to determine how reliable the algorithm is. Schroeder’s team used current source density, whereas Mendoza-Halliday’s study used anatomical data to confirm the location of Layer 4.

Still, Mendoza-Halliday says his team found some of Schroeder’s critiques reasonable and used them to create vFLIP2, which detects the motif in about 80 percent of recordings and identifies Layer 4 better than the current source density approach.

“It is quite special and uncommon to observe such a complex pattern of neuronal activity [being] preserved in such [a] high percentage of recorded cortical sites across every single area of the cortex we have recorded from,” Mendoza-Halliday says. “That must mean there is a preserved mechanism across all cortical areas. Patterns this preserved are very rarely discovered in the brain.”

The presence of the pattern “holds up to scrutiny,” says Sander van Bree, a postdoctoral researcher in Martin Hebart’s lab at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences. Despite the disagreement, the study “invites a lot of speculation and hypotheses about oscillations being causally relevant for information processing.”