Waves of calcium activity dictate eye structure in flies

Synchronized signals in non-neuronal retinal cells draw the tiny compartments of a fruit fly’s compound eye into alignment during pupal development.

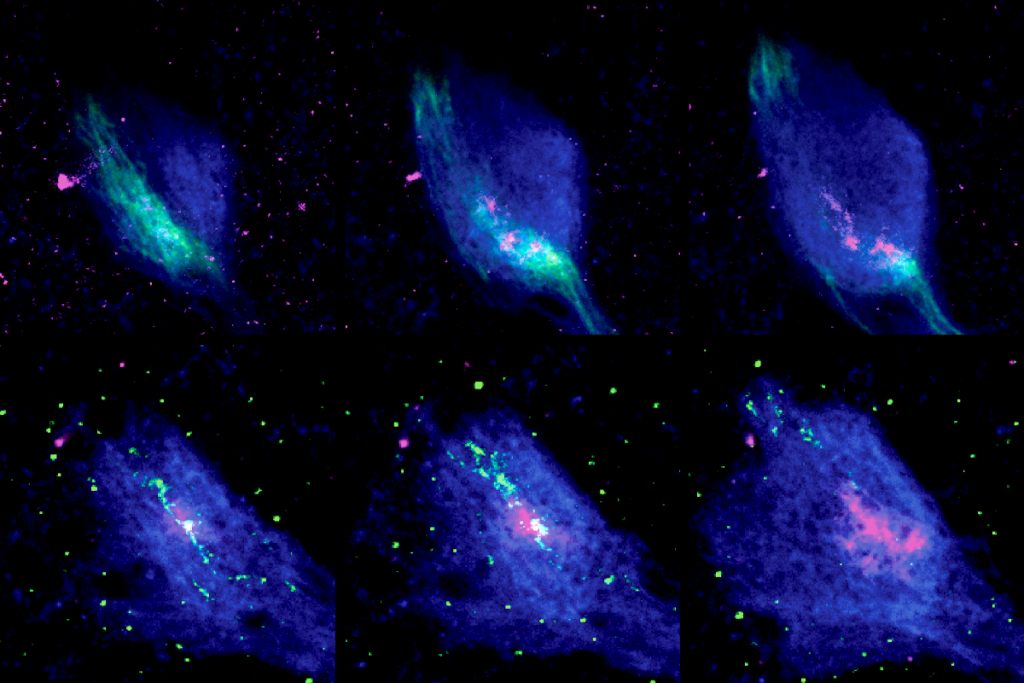

The visual system of Drosophila melanogaster gets a structural glow-up roughly 36 hours after a pupa forms: Calcium activity ripples across the retinas to create the precise architecture that enables the fruit fly to see, according to a study published last month in Science.

In people and other mammals, waves of calcium signaling in developing retinal neurons help refine the visual circuitry and prime it for sensory input. The new work suggests that non-neuronal retinal waves can organize eye tissue structure, says study investigator Claude Desplan, professor of biology and neural science at New York University.

Given the fly’s short lifespan—about three months—Drosophila tissue structure is mostly “hard-wired” by the genome, Desplan says. But the team’s results offer new evidence that flies exhibit more developmental plasticity than researchers previously acknowledged, he adds.

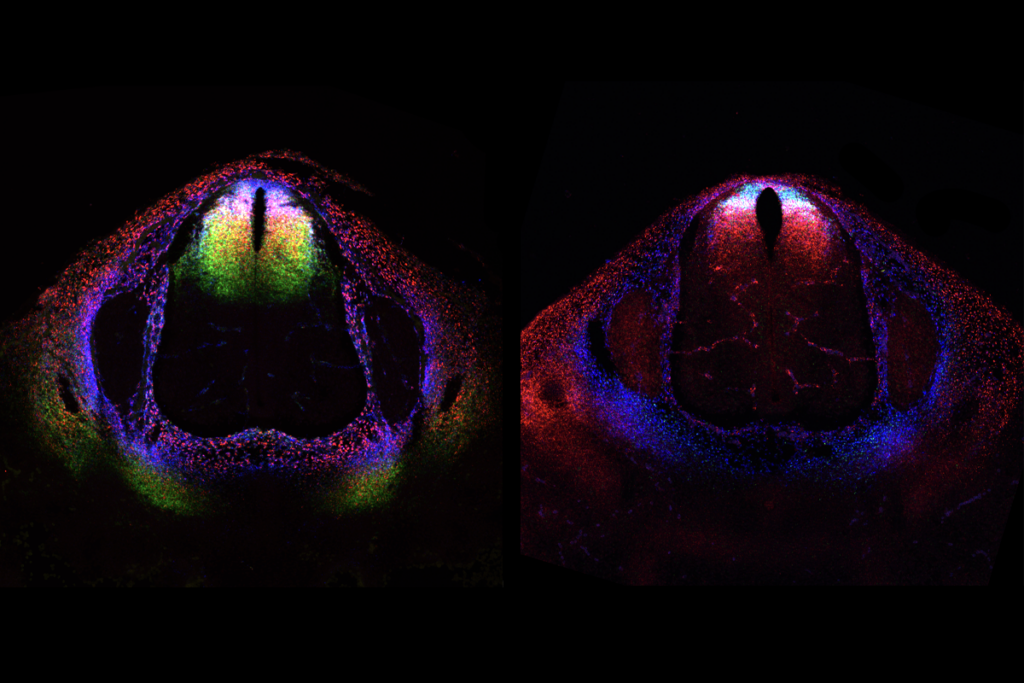

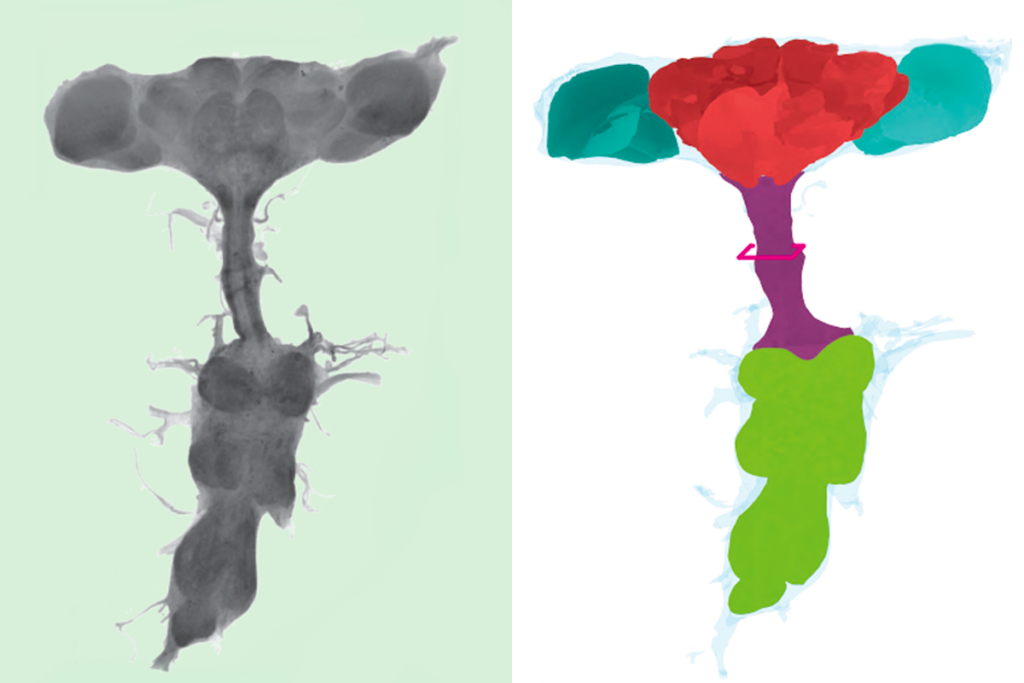

Across the fruit fly retina, hundreds of tiny optical units, or “ommatidia,” each house eight photoreceptor neurons surrounded by non-neuronal support cells. A size gradient of ommatidia equips flies for flight: Larger, ventral ones can capture more light from the dark ground, whereas smaller, dorsal ones take in the bright sky. “Everything is packed very precisely,” Desplan says.

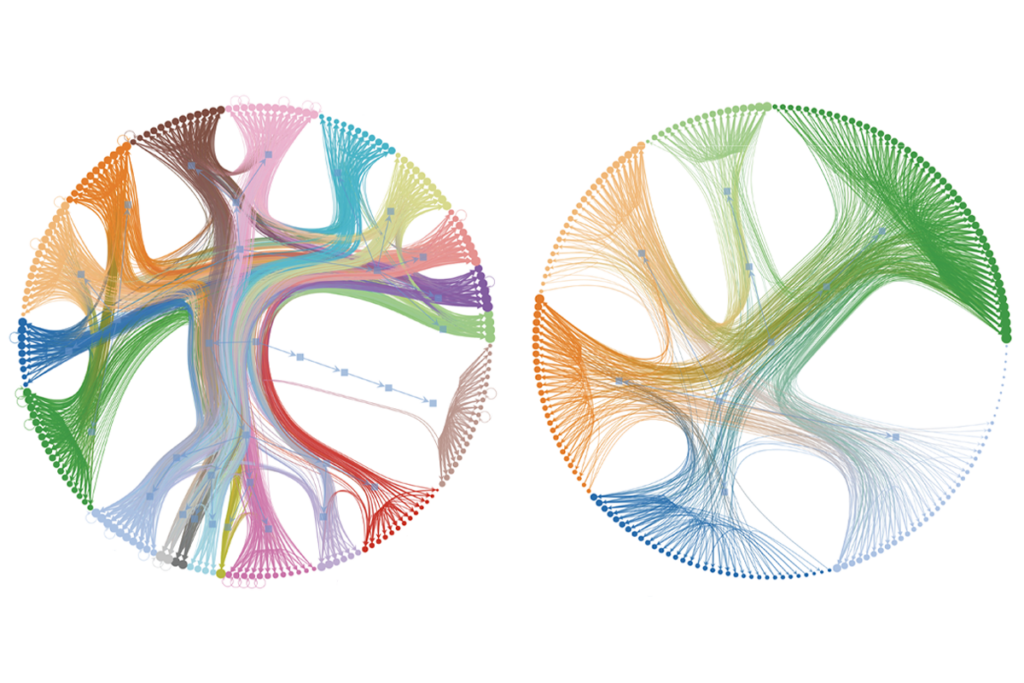

Ommatidia of all sizes need proper spacing to produce a clear image. A pupa has uneven gaps between these cell clusters at first, with wide boundaries around the larger ommatidia. Over just a few hours, however, the non-neuronal retinal waves fine-tune the spaces to make them more uniform, the new study shows.

A protein called CAD96CA, a receptor tyrosine kinase, initiates calcium release within individual ommatidial cells, Desplan’s team found. This signal propagates through gap junctions made of innexin subunits, first to other non-neuronal cells within the same ommatidium and then across interommatidial cell boundaries. Calcium activity drives contraction in interommatidial cells via the formation of an actomyosin network. Disrupting calcium waves by knocking out an innexin subunit prevents the ommatidia from coming into alignment.

I

t is not yet clear what signal sets the retinal waves in motion, as CAD96CA has no known ligands. Desplan suggests that the artificial-intelligence tool AlphaFold could help his team to identify candidate proteins.Further research could also tease out the role of different innexins that form the gap junctions, says Maike Kittelmann, senior lecturer in cell and developmental biology at Oxford Brookes University, who studies compound eye development and was not involved with the research. “Can you code how a calcium wave propagates by changing the innexin combinations between two cells that make that gap junction? I think that’s an interesting question,” she says.

In addition to the early retinal waves Desplan’s lab outlined, they also observed another period of non-neuronal calcium activity nearly 40 hours later. This signaling period was previously described in a 2021 study from an independent team, which reported that calcium waves in this second window help the retina take its characteristic convex shape.

“You don’t see [wave-like activity] everywhere in the nervous system,” says Alexandre Tiriac, assistant professor of biological sciences at Vanderbilt University, who was not involved in the new work. In mice, non-neuronal cells called Müller glia are involved in retinal waves, Tiriac adds, though the purpose of this activity is unclear. The new findings suggest that these waves could influence mammalian retinal structure, he says.

Recommended reading

Cell atlas cracks open ‘black box’ of mammalian spinal cord development

How developing neurons simplify their search for a synaptic mate

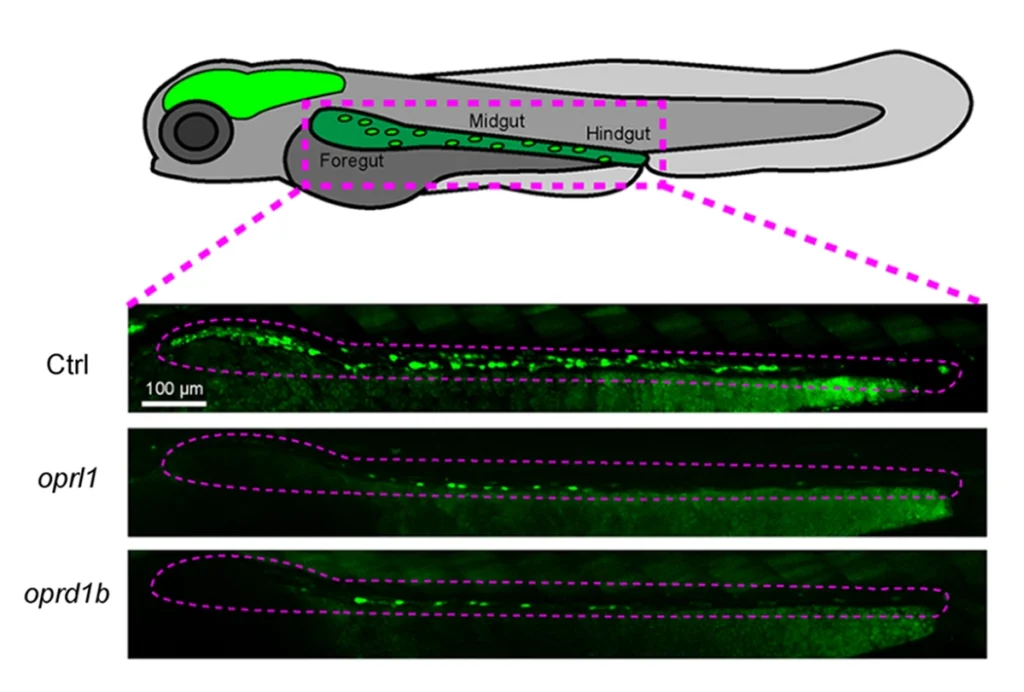

Opioid receptors may guide formation of gut nervous system in zebrafish

Explore more from The Transmitter

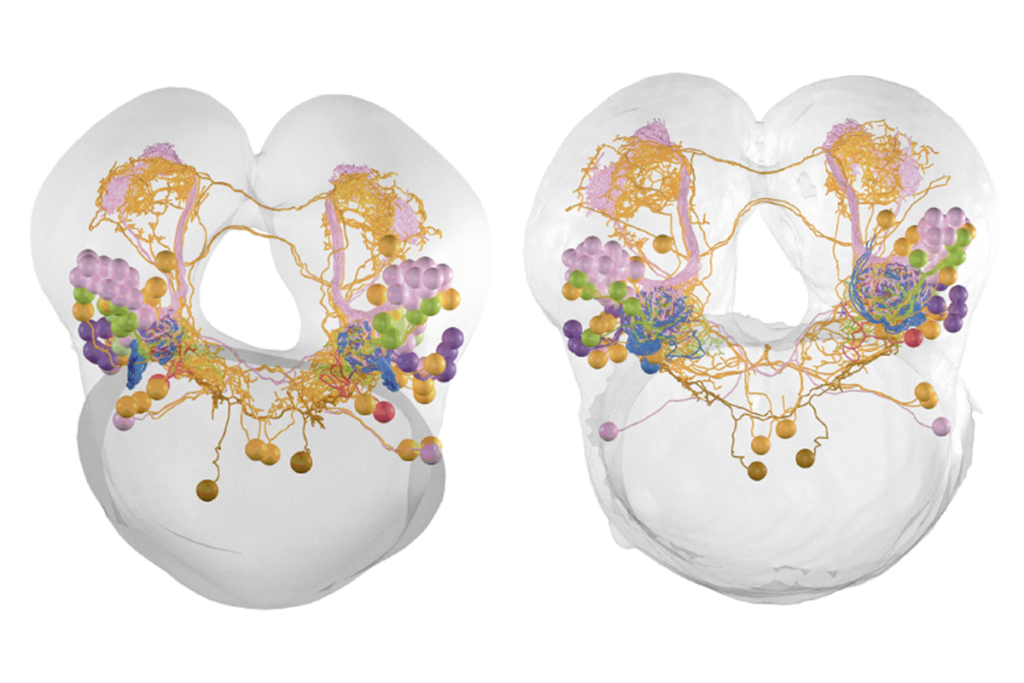

Local circuit loops within body control fly behavior, new ‘embodied’ connectome reveals

Worms help untangle brain structure/function mystery