Some facial expressions are less reflexive than previously thought

A countenance such as a grimace activates many of the same cortical pathways as voluntary facial movements.

Ever since Charles Darwin observed that nonhuman primates make facial expressions like humans do, researchers have debated whether these movements are reflexive readouts of an animal’s internal state. Such grimaces and smiles are highly stereotyped and often involuntary, suggesting they are driven by subcortical brain areas. But it turns out that emotion-driven facial expressions activate the same cortical pathways as do voluntary movements, such as chewing, according to a study published today in Science.

The findings suggest that emotion-driven facial expressions are not simply reflexive and challenge the long-standing idea that distinct cortical pathways encode emotional versus voluntary movements.

“We like to think of emotions and cognition as two separate things,” says study investigator Winrich Freiwald, professor of neurosciences and behavior at Rockefeller University. “But this shows that that distinction is likely artificial.”

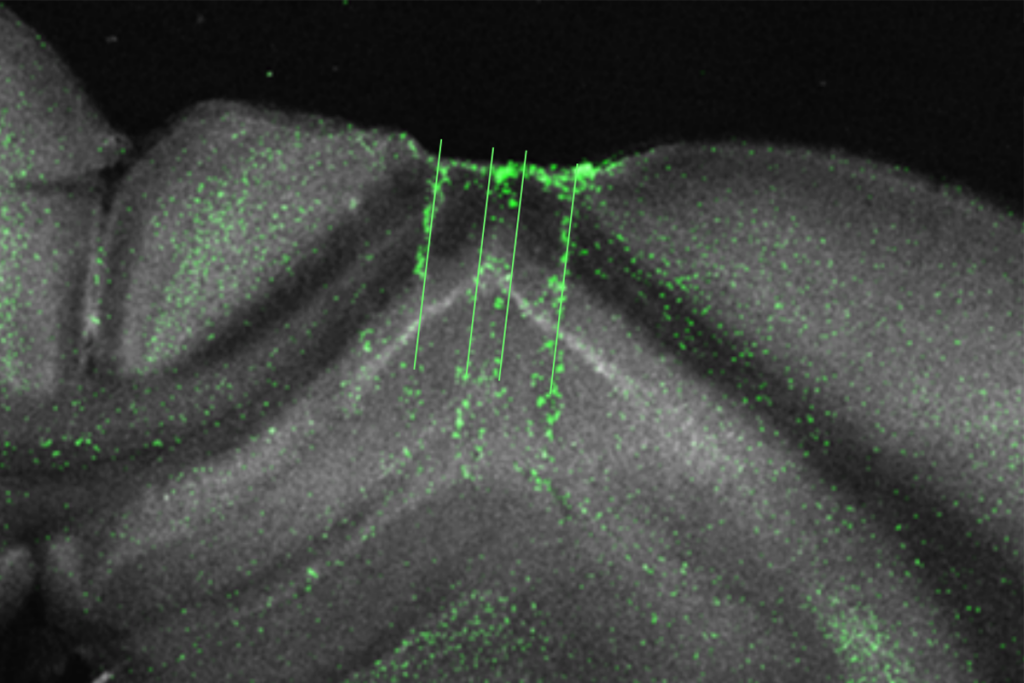

Freiwald and his colleagues used functional MRI and electrophysiological recordings to measure neuronal activity as two macaques chewed a piece of food or reacted to images of other monkeys by either making threatening expressions or smacking their lips, a sign of cooperation.

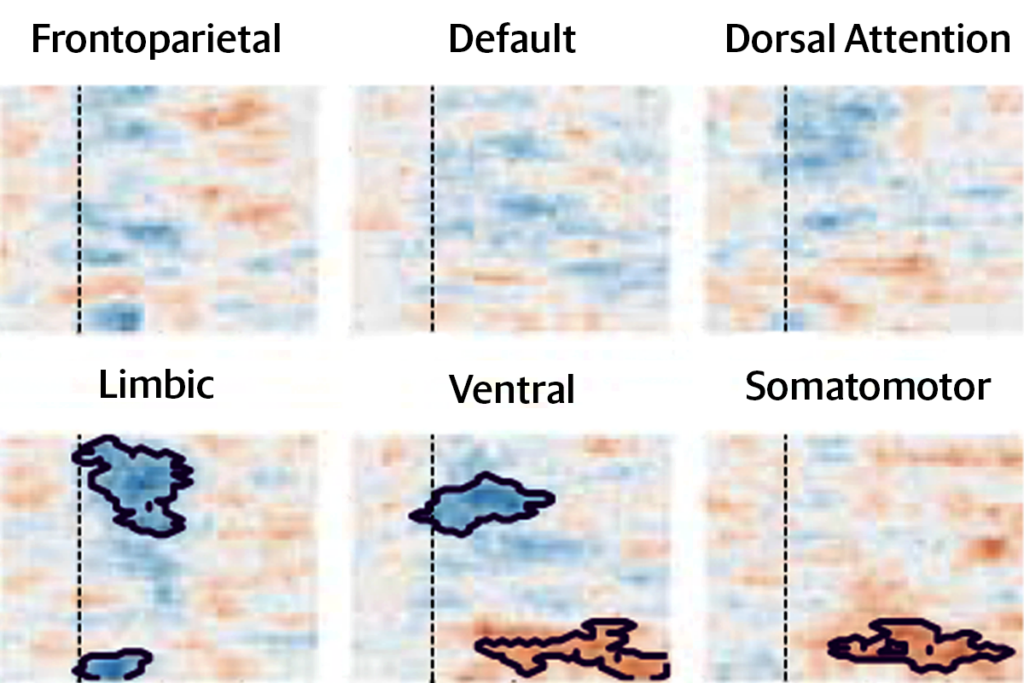

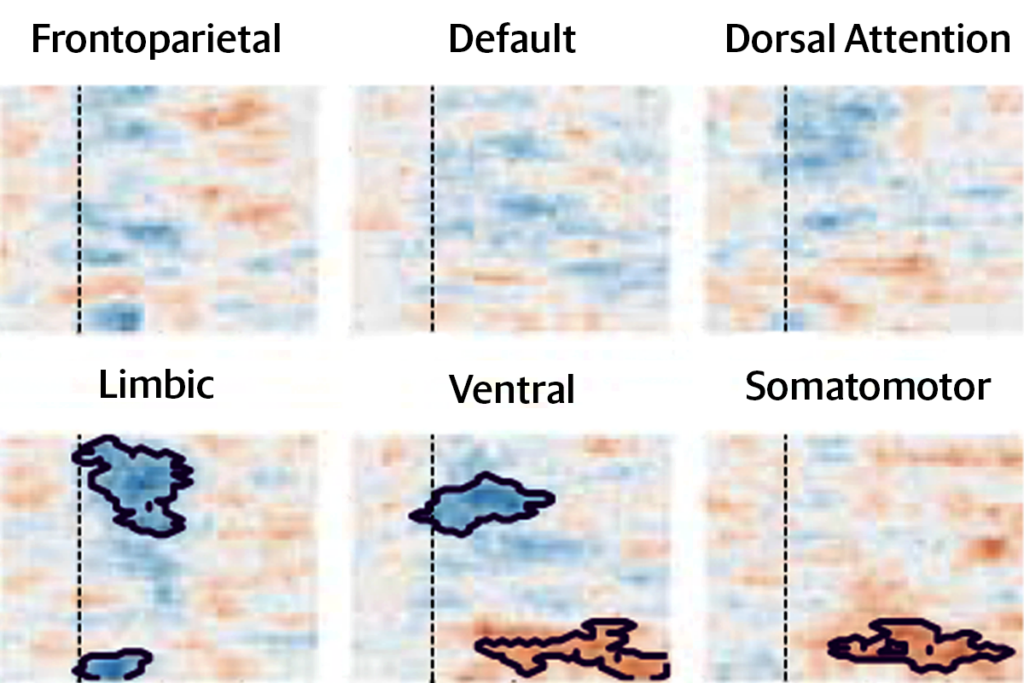

Previous electrostimulation, lesion and neuropsychology research strongly suggested that medial cortical areas, which receive significant subcortical input, drive emotional actions, Freiwald says. So he and his colleagues anticipated significant differences in how the lipsmacking and threatening movements would relate to neuronal activity across facial motor areas—particularly the primary motor cortex, ventral premotor cortex, somatosensory cortex and cingulate motor cortex—when compared with chewing.

Although the three gestures—chewing, grimacing or lipsmacking—each produced a distinct pattern of neuronal population activity, all four brain areas contained cells that fired when the monkeys made any of the gestures. Each area contained comparable mixtures of broadly tuned “gesture-general” neurons and narrowly tuned “gesture-specific neurons,” the researchers found.

The strong intermixing of emotion-driven and voluntary actions provides compelling evidence for more distributed coding of emotionally driven behavior than previously thought, says Michael Platt, professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania. “It’s almost like this ‘everything, everywhere, all at once’ type of coding,” he says.

T

Medial cingulate cortex activity remained stable before and throughout the movement, and the premotor cortex showed moderately stable activity at an intermediate timescale. This suggests that cortical coding of both voluntary and emotional facial expressions is hierarchical, with information flowing from the cingulate cortex to the primary motor and somatosensory cortices, which ultimately send signals to the muscles of the face, driving real-time adjustments.

Neurons that encode gestures before the movement occurs may therefore represent an animal’s internal state rather than the movement itself. These neurons are well positioned to both receive and integrate top-down contextual information, regardless of whether monkeys are making emotional or voluntary gestures, Freiwald says. These types of cells are concentrated in the cingulate cortex but found in all areas.

The existence of these movement-independent cells “fundamentally changed how I think about emotions,” Freiwald says, suggesting that emotion-driven movements may be more voluntary than previously appreciated.

The results complement a study published last month by Freiwald’s team that shows the areas that encode voluntary and emotion-driven facial movements are highly interconnected in macaques. The work adds to a growing body of evidence that cortical areas shape emotions. For example, facial movements convey decision-making variables in mice, and emotional responses in people engage vast swaths of cortex.

“There’s a strong current in neuroscience and psychology that wants us to think of emotions not as reflexive behaviors but as tools to communicate with other people,” says Sebastian Korb, senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Essex, who was not involved in the study published today. Still, he adds that he is not 100 percent sold on this idea. As a counterexample, people who have lesions in one of the lateral cortical areas, which include the primary motor cortex, often have facial paralysis on the opposite side but typically can smile with both sides of their face, Korb says, providing strong evidence of at least some functional specificity.

“There’s a difference between what an area does and what information is available there,” Platt says. So although there may be similar signals in different regions of the cortex, those regions may make different computations with the same information. Ultimately, experiments selectively manipulating these signals in the brain can clarify the extent to which different brain areas are functionally segregated. “We need to figure out what the signals are for,” he adds.

Regardless, the findings strongly suggest that emotions and cognition “likely can’t exist in isolation,” Freiwald says. Each can influence the other, he says. “There’s awareness of your current situation that shapes your thinking and feeling.”

Recommended reading

Eye puffs prompt separable sensory, affective brain responses in mice, people

Hippocampus builds reputation as ‘general-purpose statistical learning machine’

Explore more from The Transmitter

Facial movements telegraph cognition in mice

Eye puffs prompt separable sensory, affective brain responses in mice, people