Viral remnant in chimpanzees silences brain gene humans still use

The retroviral insert appears to inadvertently switch off a gene involved in brain development.

An ancient viral infection might have shaped chimpanzee brain development and helped set chimps apart from humans and our other primate relatives, according to a recent preprint.

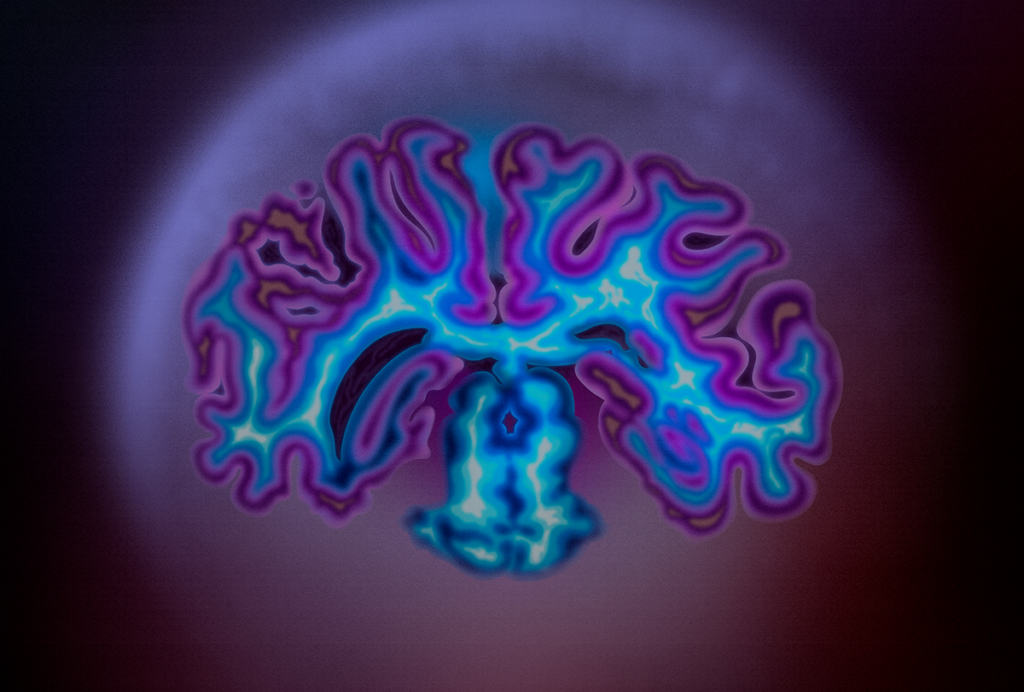

A remnant of the virus’s DNA—which appears in the chimpanzee genome but not in that of humans—inadvertently silences a noncoding RNA that is widely expressed in the developing human brain, the new study reveals.

The results help explain why humans are “different from chimpanzees when we almost have exactly the same gene repertoire,” at least as far as protein-coding genes are concerned, says Jason Shepherd, professor of neurobiology at the University of Utah, who wasn’t involved in the study. Instead of simple mutations in protein-coding regions, “here you’ve got these external environmental factors that can ultimately influence the evolution of organisms,” he says.

The results add to growing recognition that endogenous retroviruses play a role in evolution and development, says Welkin Johnson, professor of biology at Boston College, who was not involved in the work. Although, he adds: “I’m not sure I know of another compelling case that involves humans and chimps.”

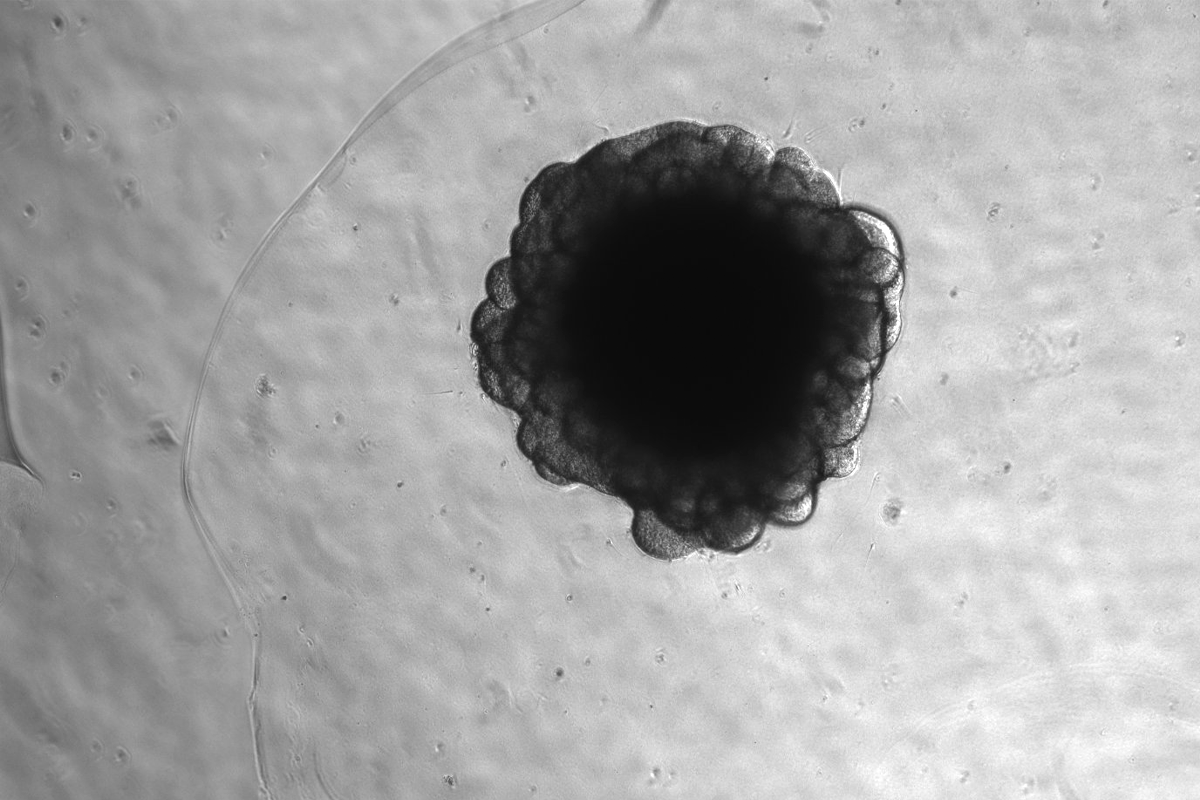

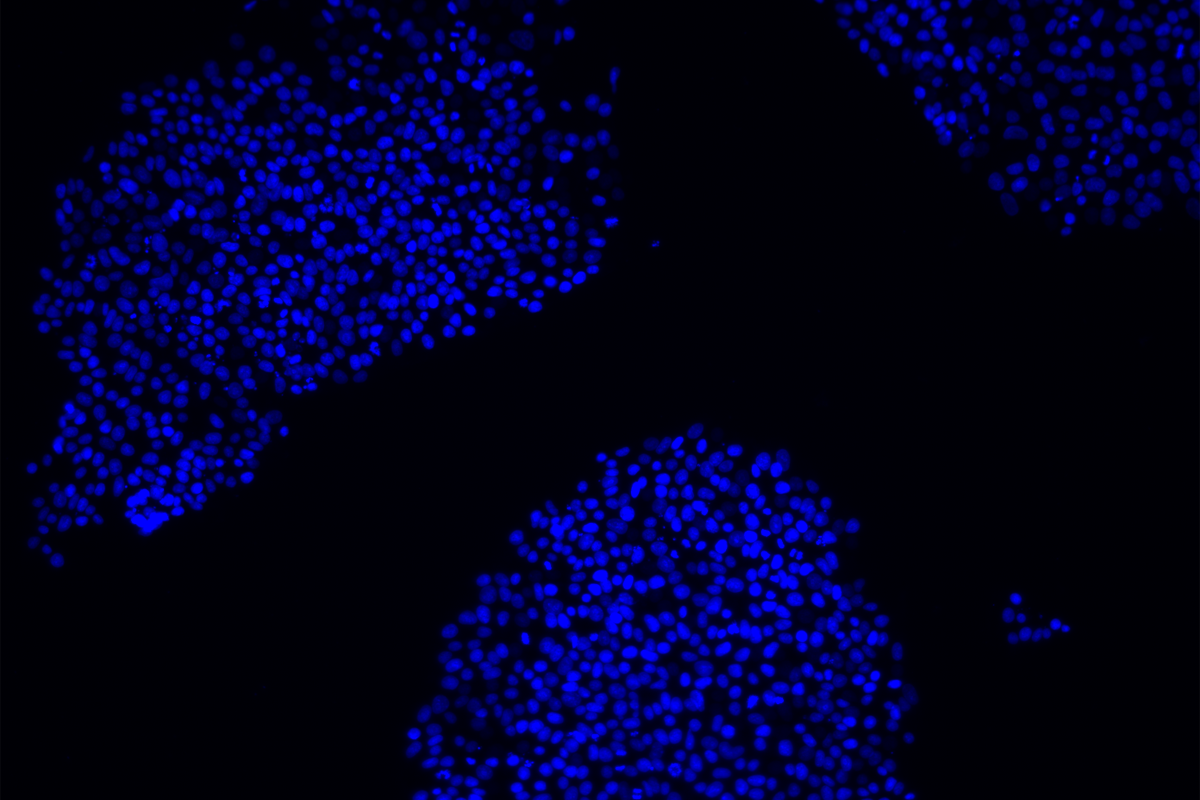

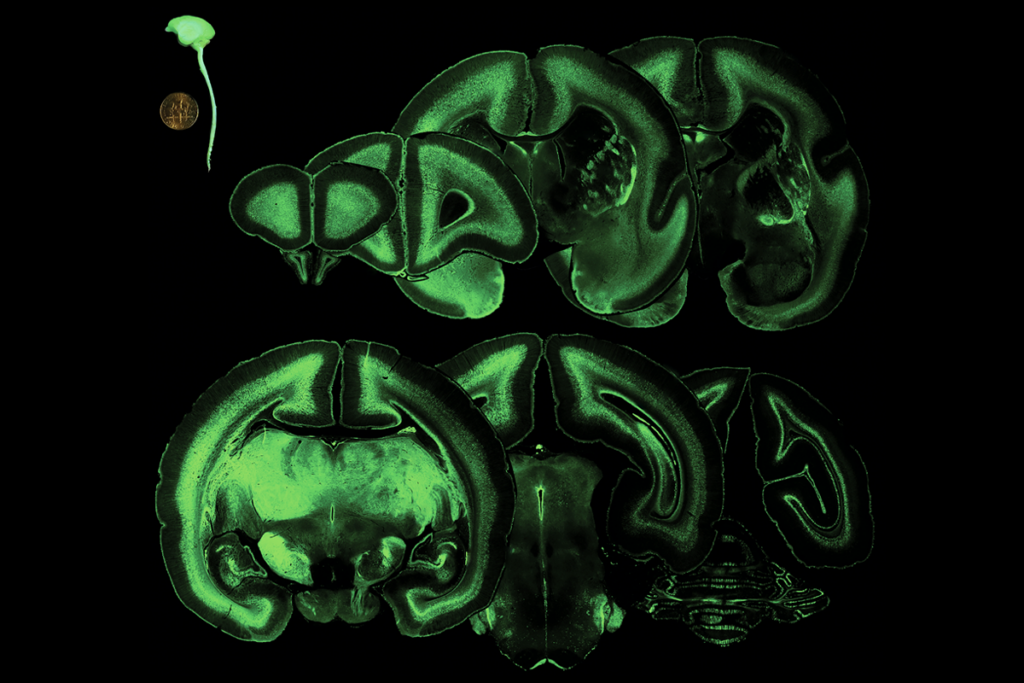

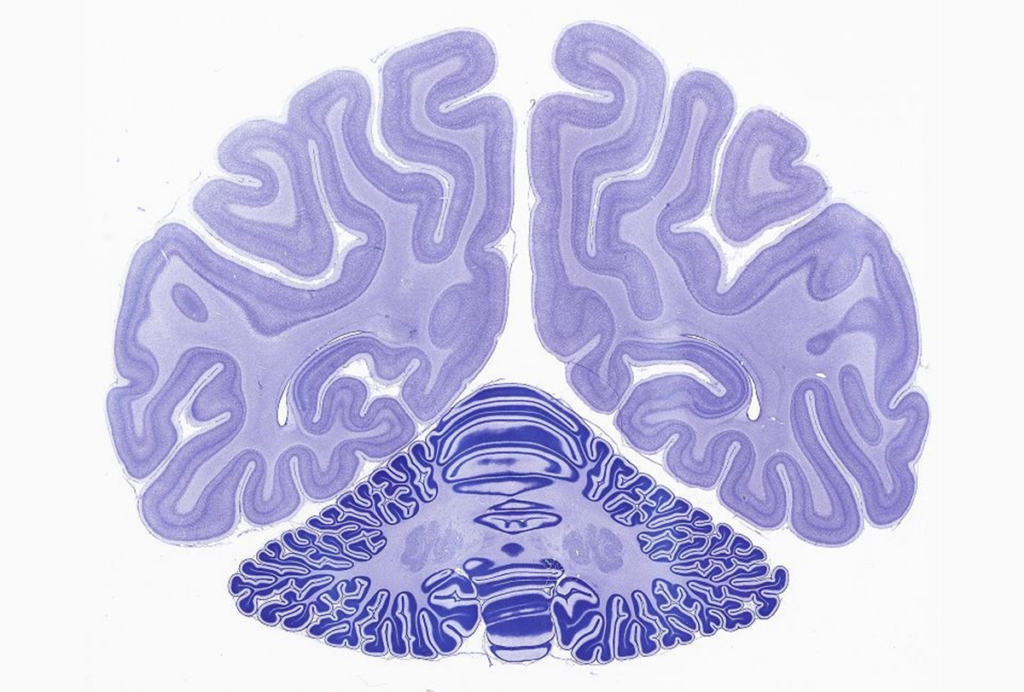

The chunk of viral DNA called Pan troglodytes endogenous retrovirus 1, or PTERV1, has replicated itself about 158 times across the chimpanzee genome, the team discovered by studying 15-day-old human and chimpanzee neural organoids. The two species’ organoids display similar characteristics at this stage of development, making it the appropriate age for comparison, says study investigator Johan Jakobsson, professor of molecular neurogenetics at Lund University.

All these PTERV1 insertions, which are fixed in the germ line and passed down from one generation to the next, are epigenetically silenced by methylation, long-read sequencing showed. The findings were posted on bioRxiv in December.

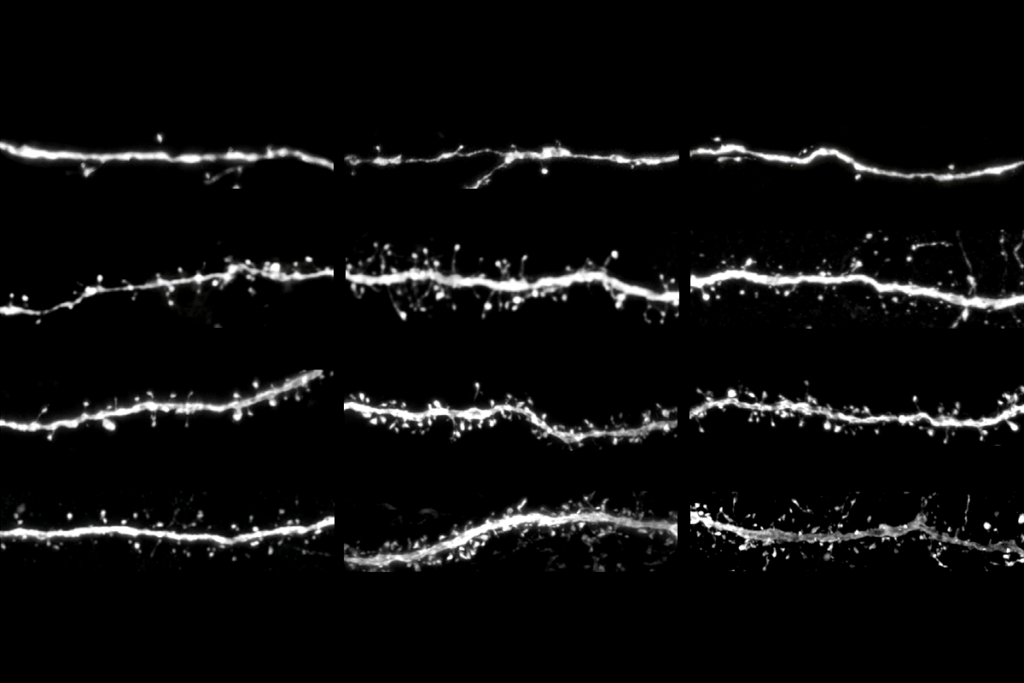

Methylation is one of the ways host genomes silence viral insertions, but researchers have long suspected that it can also switch off host genes, says Patricia Gerdes, a postdoctoral researcher in Jakobsson’s lab who led some of the experiments in the new study.

In total, 46 genes reside near a PTERV1 insert, of which 11 showed a slightly different expression pattern when the researchers compared 15-day-old chimpanzee and human organoids. The sharpest contrast appears for the gene that encodes a long noncoding RNA called LINC00662, which is completely silenced in chimpanzees but expressed strongly in human organoids.

The LINC00662 sequence on chromosome 19 is interrupted by a PTERV1 insertion and is epigenetically silenced in chimpanzee organoids, the new study found. But induced pluripotent stem cells derived from chimpanzees expressed the gene after the team excised this insert using CRISPR-Cas9.

I

Although retroviral infections are common, it is rare for them “to insert in the genome successfully most of the time, and especially into a germ line,” says Emily Casanova, assistant professor of neurology at Saint Louis University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study. When they do, the host tends to either silence the viral insert or co-opt it. For example, the ARC gene, which mediates long-term memory storage in tetrapods and flies, originated from independent retroviral entries into the germ lines of these two lineages.

The study shows the power of investigating long noncoding RNAs and other noncoding regions, which are relatively understudied, in organoids to understand what they’re doing in closely related species, according to Jonathan Stoye, emeritus endogenous retrovirologist at the Francis Crick Institute, who was not involved in the work.

PTERV1 was discovered in 2005, but the new research was not possible until the recent advances in long-read sequencing and brain organoids, says Gerdes, who spent two years finessing the protocol. Chimpanzee organoids are a particularly new development and still require significant fine-tuning, she adds.

PTERV1 likely entered the chimpanzee genome when the virus infected the last common ancestor of chimpanzees and bonobos nearly 5 million years ago. It is also found in macaques and gorillas, which might be the result of separate infections, Jakobsson says. Humans escaped the virus, possibly because human ancestors were geographically separated from where the virus was most active, but it is also possible that they successfully fended off the virus, limiting its spread in the population, Casanova says. How PTERV1 and other endogenous retroviruses regulate gene expression and influence primate brain evolution remains underexplored, Casanova says.

One next step is to understand what LINC00662 does in developing human neural tissue, Shepherd says. “This is hard to do when it’s a human-specific transcript,” he adds, “but there’s ways to do it in different contexts and even making sort of humanized mouse models.”

Recommended reading

Prenatal viral injections prime primate brain for study

Nonhuman primate research to lose federal funding at major European facility

Systems and circuit neuroscience need an evolutionary perspective

Explore more from The Transmitter

Protein tug-of-war controls pace of synaptic development, sets human brains apart

Constellation of studies charts brain development, offers ‘dramatic revision’