Artificial-intelligence agents have amazing strengths, but also weaknesses. They are great at coding: They can translate ideas into working computer programs much faster, and with fewer bugs, than nearly all humans. The newest agents are so good at math that the International Mathematical Olympiad now asks AI companies to give human participants one day to enjoy their success before announcing the AI results. And these agents are also getting good at visual reasoning, such as interpreting graphical data plots. On the flip side, “hallucinations” still occur, and they can have real consequences. For example, lawyers have faced financial penalties for citing nonexistent cases that were hallucinated by large language models.

Scientists are excited about the possibilities—indeed, more than 60 percent of researchers now use AI to help with their work—but they are understandably cautious about putting too much trust in LLMs until we establish ways to ensure rigor.

So how can we take advantage of a system with so much potential but also risk? If you just ask a chatbot to solve a difficult research question, it will flounder. Humans are the same: If you give a Ph.D. student a difficult problem and then walk away, don’t expect success. You have to give them a problem they can solve; even more important, they need a way to know when they have found a genuine solution. Similarly, if an AI system has a way to verify when a proposed solution is correct, there is no risk of hallucinating incorrect answers. One way to do this is to write a fixed piece of code that objectively scores any candidate solution.

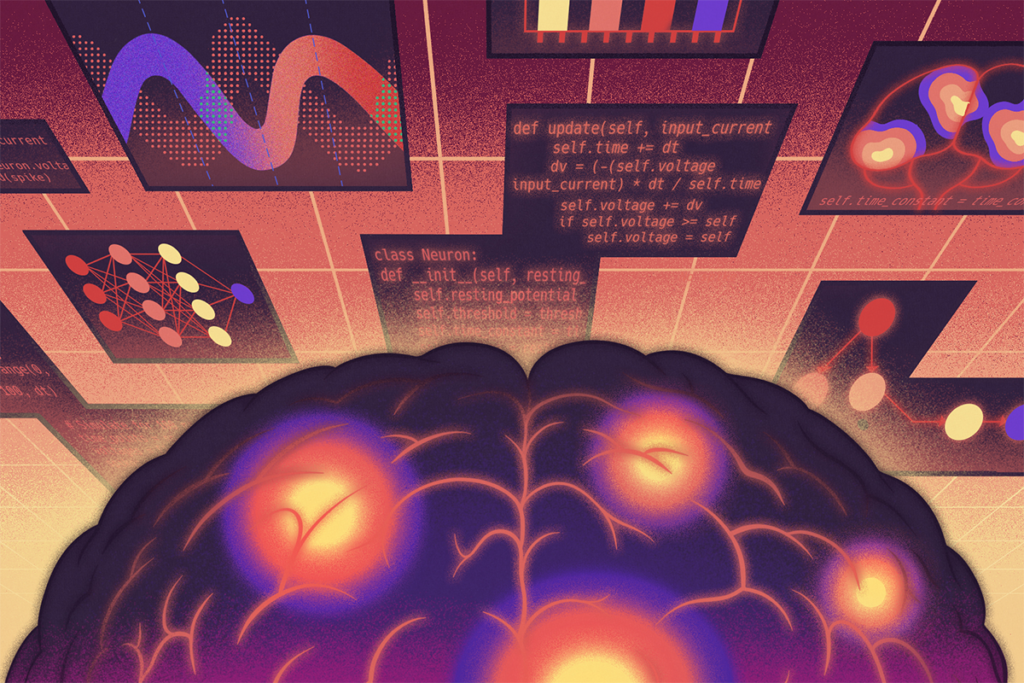

Our lab recently applied this approach to a problem in visual neuroscience. Recordings from mouse V1 show a high-dimensional population code for orientation, but standard equations for single-neuron tuning curves—smooth, double-Gaussian bumps—predict a lower dimensional code. High-dimensional codes have important consequences for how the brain processes information. But we had not been able to come up with equations that both matched single-cell tuning curves and predicted high dimensionality at the population level.

To address this conundrum, we turned it into a game an AI system could play. The AI’s task was to write Python programs predicting a neuron’s response to visual stimuli, given parameters of the neuron’s tuning. Each program was scored automatically by a fixed pipeline that measured how well the equation encoded by the program fit experimental data. The AI system’s job was simply to produce new programs with a better score. We used an evolutionary strategy: At each step, the system prompted an LLM to write a new program that improved on previous efforts. The prompt included the source code and scores of previous attempts, along with plots showing how these previous attempts deviated from actual neuronal tuning curves, which the LLM could interpret with its machine vision. LLM-generated programs with good scores were quoted in future prompts. The system ran for 45 minutes, during which time it evaluated a few hundred candidate equations, for a cost of $8.25 of LLM tokens—orders of magnitude cheaper than some previous approaches.

T

Because the end product was a compact analytical equation rather than a black-box neural network, we could explain why it works mathematically. To produce a high-dimensional code, a tuning curve cannot be infinitely differentiable; it must have spiky peaks, as in the AI’s tuning equation. The humans knew this but had not told the AI system, which found the spiky peaks because of their modest improvement to single-cell tuning, which again left the humans wondering why we didn’t think of it first. Finally, because the AI system gave us a simple equation, we could use it to investigate the computational benefits of the resulting high-dimensional code and to show that similar coding occurs in other systems such as head-direction cells.

This case illustrates one way AI science might play out in the next year or so. AI won’t do anything you couldn’t have done yourself. Instead, it will do things you could have done yourself but, for whatever reason, didn’t—and it will do it much faster. Adding an AI scientist to a team will be like adding a human collaborator—not an outstandingly creative collaborator, but one who works nonstop, is great at coding and knows about all fields of science, so it can bring ideas like the stretched exponential function from other disciplines.

Given clear instructions and an objective way to measure its success, such a system can significantly boost productivity. But it can’t do everything. In this instance, human researchers set up the objective, chose the scoring function, curated the data, and recognized why the solution was scientifically meaningful. The LLM’s contribution was not a radical new insight but a steady stream of ever-improving equations, explored much faster and more systematically than a human could manage. The payoff came when a human-understandable equation emerged from this process, because that enabled theory, proofs and new experiments that would have been opaque with a black-box deep net.

Even though current AI systems are unreliable, this project shows one way to make use of them: Turn your hard scientific question into a set of concrete, checkable proposals, wire up an automatic scoring loop, and let the AI iterate. The creativity is still mostly human, in choosing the question and the objective; the AI’s strength is relentless, moderately clever trial-and-error in the space of technical solutions. For now, that combination is already enough to resolve real, long-standing puzzles in neuroscience—and there is every reason to think that this style of collaboration will become a standard part of how science is done over the next year or two.

After that, who knows.