Remembering GABA pioneer Edward Kravitz

The biochemist, who died last month at age 92, was part of the first neurobiology department in the world and showed that gamma-aminobutyric acid is inhibitory.

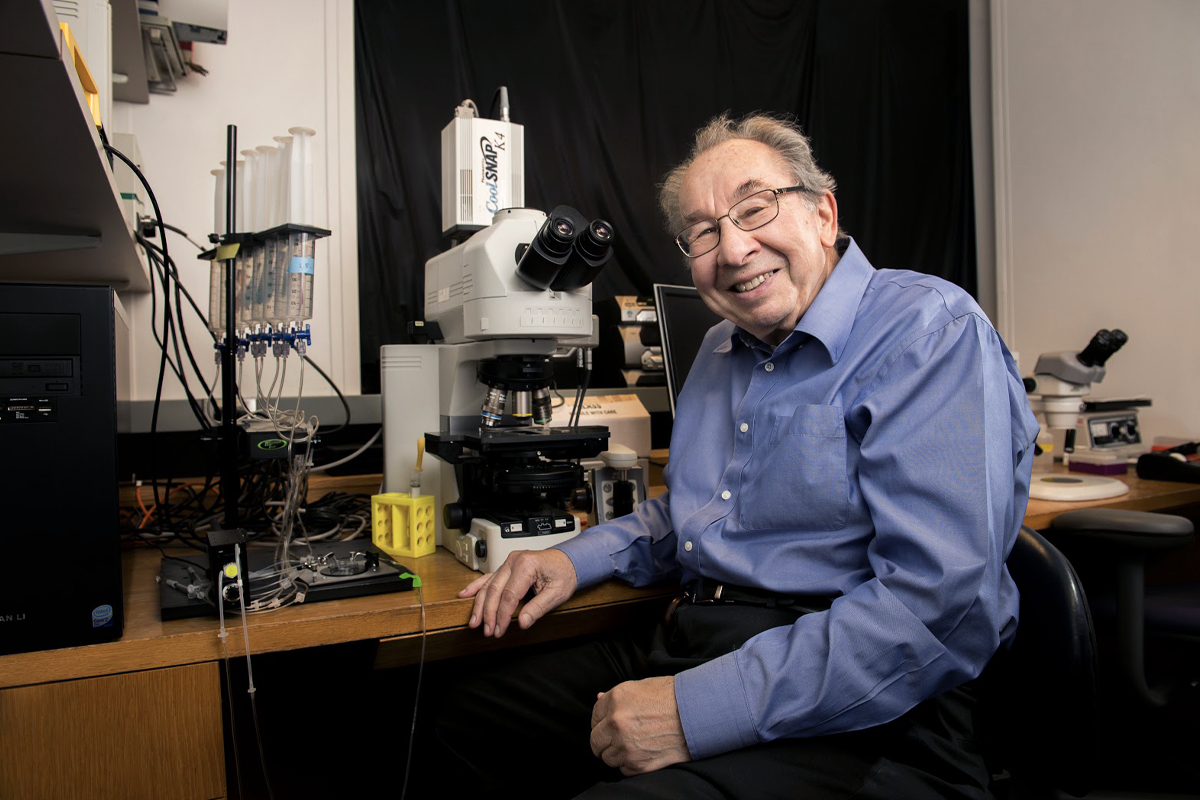

In 1961, Edward Kravitz set out to clear up a long-standing debate about gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) once and for all.

Kravitz, a biochemist, had just joined Harvard Medical School as instructor in pharmacology. He and his colleagues suspected GABA was a neurotransmitter, an idea at odds with the then-prevailing view that neuronal communication was largely electrical; even those who conceded the existence of chemical messengers recognized only two small molecules, acetylcholine and norepinephrine, as bona fide neurotransmitters.

Kravitz’s GABA team, as he called his colleagues, painstakingly dissected the muscle and nerves of a lobster, the lab’s animal model, and then stimulated the excitatory and inhibitory connections to see if GABA would be released, recalls Zach Hall, a now-retired neuroscientist who was the first graduate student in Kravitz’s lab.

Hall had graduated and was on his way to California when he says he got word from Kravitz: Their experiment had worked. The team’s seminal study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 1966, showed that stimulating inhibitory neurons caused them to release GABA, cementing the molecule’s role as a neurotransmitter alongside acetylcholine and norepinephrine. “We knew that by adding a third compound to that list we would be doing something of great importance,” Kravitz wrote in a 2004 autobiography.

Over the course of his career, Kravitz extended his research well beyond his biochemical roots, studying aggression in lobsters, developing new techniques for the neuroscience field and, at one point, even shifting to study Drosophila genetics.

A jokester at heart, Kravitz masterfully balanced fun and rigor, holding himself—and his team—“to the highest standards,” says Thomas Schwarz, professor of neurology and neurobiology at Harvard Medical School, who did his Ph.D. in Kravitz’s lab. The approach was “get the work done but have a good time doing it.”

Kravitz, who died at the age of 92 on 21 September, had just retired from Harvard last year. “I don’t feel any place near the end of my active scientific life, despite attempts of deans and others to hasten the happening of that sorry event,” he wrote in his autobiography.

“He didn’t ever want to give up,” says John Hildebrand, professor emeritus of neuroscience at the University of Arizona, who spent two years as a postdoctoral researcher in Kravitz’s lab. “He never stopped thinking about the next great thing to do.”

K

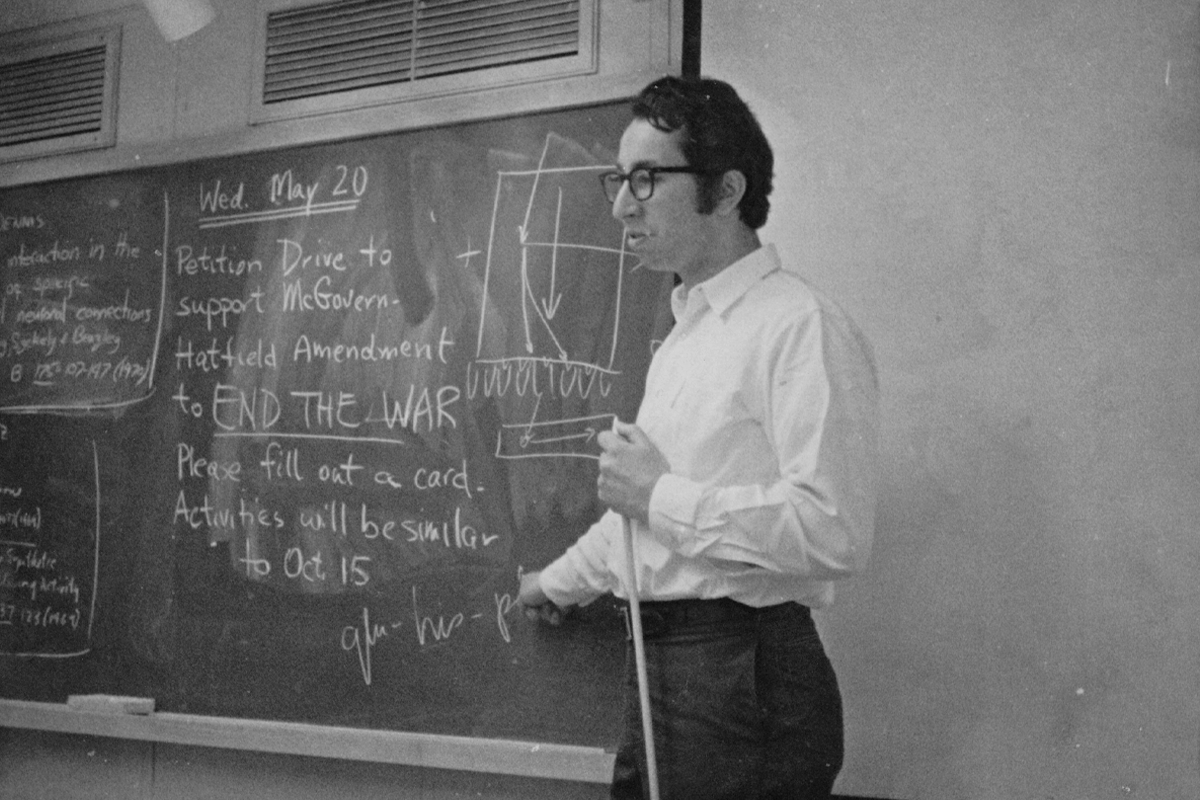

ravitz became “hooked” on working in the lab after he earned his B.S. at City College of New York and then stumbled upon a job opportunity as a research assistant at Sloan-Kettering Hospital, according to his autobiography. That led him to pursue a Ph.D. in biological chemistry at the University of Michigan, where he studied how inorganic phosphate regulates glucose metabolism.During this time, he debated with philosophy graduate students about “whether we ever could understand how nervous systems worked through biochemical or physiological studies,” which sparked his interest in neuroscience, he wrote in his autobiography.

But Kravitz didn’t act on that interest until 1961, when he received a call from Stephen Kuffler at Harvard Medical School. Kuffler was putting together an interdisciplinary neurophysiology team, which included David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel, and was looking for a biochemist to join their ranks. Although the neuroscience papers he read were “full of incomprehensible squiggles, unfamiliar abbreviations, and cartoons,” Kravitz wrote, the move “just seemed to make sense.” This team would go on to be a part of the world’s first neurobiology department, established at Harvard in 1966.

As soon as he joined the Harvard faculty, Kravitz got to work trying to purify a peptide he thought might be a transmitter, but even with his biochemical background, he was unsuccessful. So he shifted his focus to GABA, which Kuffler and others had shown was present in the crustacean nervous system and might be a chemical messenger. Even after Kravitz’s groundbreaking work on GABA, many still doubted the findings. A decade later, an independent team of researchers published work showing that GABA is an inhibitory neurotransmitter in mice. But “the fact is that [Kravitz] had beaten them by 5 or 10 years,” says Ronald Harris-Warrick, professor emeritus of biological sciences at Cornell University, who did a postdoc with Kravitz.

Yet he didn’t stop at GABA: His lab also identified octopamine, an analog of norepinephrine, as an important invertebrate neurotransmitter and found that acetylcholine functions as a sensory transmitter in lobsters.

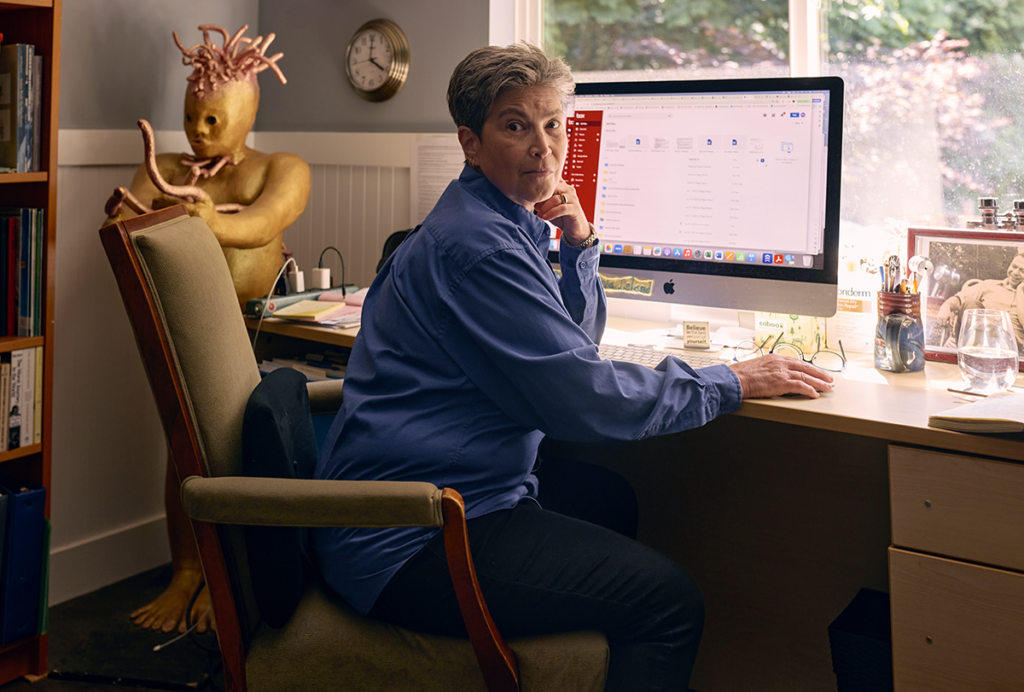

Then, while studying the neurotransmitter serotonin, Marge Livingstone—a doctoral student at the time and now professor of neurobiology at Harvard Medical School—discovered something that brought Kravitz into the world of neuroethology. One day, during one of the many summers the lab spent at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, Livingstone called to Kravitz to show him two lobsters, he wrote in his autobiography. One, injected with serotonin, had a dominant posture, whereas the other, injected with octopamine, had a submissive posture. The two molecules, Kravitz and his colleagues went on to show, serve to modulate behaviors such as fighting and retreat from fighting.

“[A neuromodulator’s] purpose is not simply to excite or inhibit a neuron but to change how that neuron works and how it can compute,” Harris-Warrick says. Kravitz “was one of the very, very earliest people who understood that there are actions of some neurotransmitters which are quite different from the rest of them.”

A

fter decades of studying the lobster, Kravitz realized that to fully understand the underpinnings of behavior, he needed to work in an animal model with well-known genetic data. At 70 years old—a time when other scientists might think about retiring—he did something that was “really bold and amazing,” Hildebrand says: Kravitz remade himself and became an expert in Drosophila genetics.He focused on aggression in the flies, creating new protocols for the field; identifying the fruitless gene as an important regulator of both courtship and aggression; and revealing the role of learning and memory in establishing social status after fighting.

Kravitz knew that scientific advances typically involved new techniques, says Antony Stretton, professor emeritus of integrative biology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. In 1968, he and Kravitz tested 120 dyes before ultimately homing in on one called Procion yellow that outlined neuronal architecture.

That discovery “opened up a huge field” that enabled scientists to visualize neurons, Harris-Warrick says. “Time after time after time, Ed made fundamental discoveries that changed the direction of science.”

In the lab, Kravitz “built a family within a family,” always making people feel welcome, Hildebrand says. He would take a break to eat chocolates with the team and helped coordinate lunches and seminars that brought the department together. Kravitz and his wife Kathryn, whom he met during the final year of his Ph.D. and had two sons with, hosted parties filled with dancing, sing-alongs and his famous margaritas, Hildebrand recalls. “It was always cheerful, fun and very much a matter of building relationships.”

He was well known for his humor and enjoyed making people laugh, performing his famous “suit joke” (which “involved extensive, rather ridiculous-looking body contortions around a new suit that didn’t fit properly,” according to his autobiography) at every department Christmas party. During one party, Hall recalls Kravitz coming out of a birthday cake. “Oh God, why can’t I have a normal adviser?” Hall says he thought at the time.

But “in spite of all the sort of unbuttoned, folksy style,” Schwarz says, “he was terribly serious about the science—colossally rigorous.”

He also took social issues seriously: Kravitz championed early efforts to diversify the pool of medical students at Harvard Medical School, and he protested the Vietnam War. And he had a passion for teaching: He established Harvard’s Neurobiology of Disease course and founded and directed the university’s Program in Neuroscience. He also directed the Neurobiology course at the Marine Biological Laboratory.

“He will certainly be remembered for those discoveries, but he will also be remembered for his humanity, for his social conscience and his desire to help those less fortunate than he,” Harris-Warrick says.

After his retirement, Kravitz and his wife moved to an assisted-living facility, but he missed academia, Stretton says. When he looked in the mirror, Kravitz still saw a “hardcore scientist,” he adds.

María de la Paz Fernández, who did her postdoc with Kravitz and is now assistant professor of biology at Indiana University Bloomington, recalls that during her most recent Zoom chat with Kravitz in July, he wanted to know how she was doing in her new position. When she asked Kravitz how he liked the new assisted-living facility, he said that the people were very nice, she remembers: “‘But there’s a problem,’ he said. ‘Well, they’re all very old.’”

Recommended reading

Remembering Adam Kampff, neuroscience educator and researcher

Remembering Mark Hallett, leader in transcranial magnetic stimulation

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering A. James Hudspeth, hair cell explorer