One of Clay Holroyd’s mostly highly cited papers is a null result. In 2005, he tested a theory he had proposed about a brain response to unexpected rewards and disappointments, but the findings—now cited more than 600 times—didn’t match his expectations, he says.

In the years since, other researchers have run similar tests, many of which contradicted Holroyd’s results. But in 2021, #EEGManyLabs announced that it would redo Holroyd’s original experiment across 13 labs. In their replication effort, the researchers increased the sample size from 17 to 370 people. The results—the first from #EEGManyLabs—published in January in Cortex, failed to replicate the null result, effectively confirming Holroyd’s theory.

“Fundamentally, I thought that maybe it was a power issue,” says Holroyd, a cognitive neuroscientist at Ghent University. “Now this replication paper quite nicely showed that it was a power issue.”

The two-decade tale demonstrates why pursuing null findings and replications—the focus of this newsletter—is so important.

H

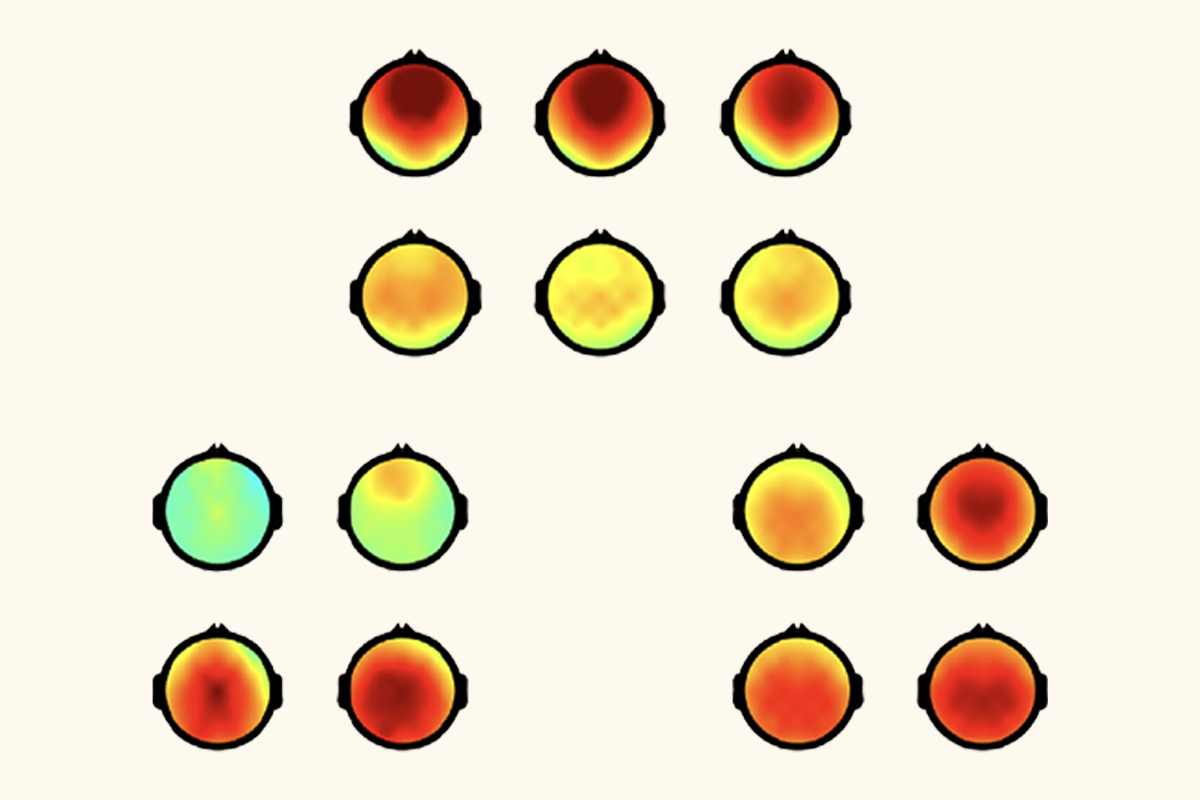

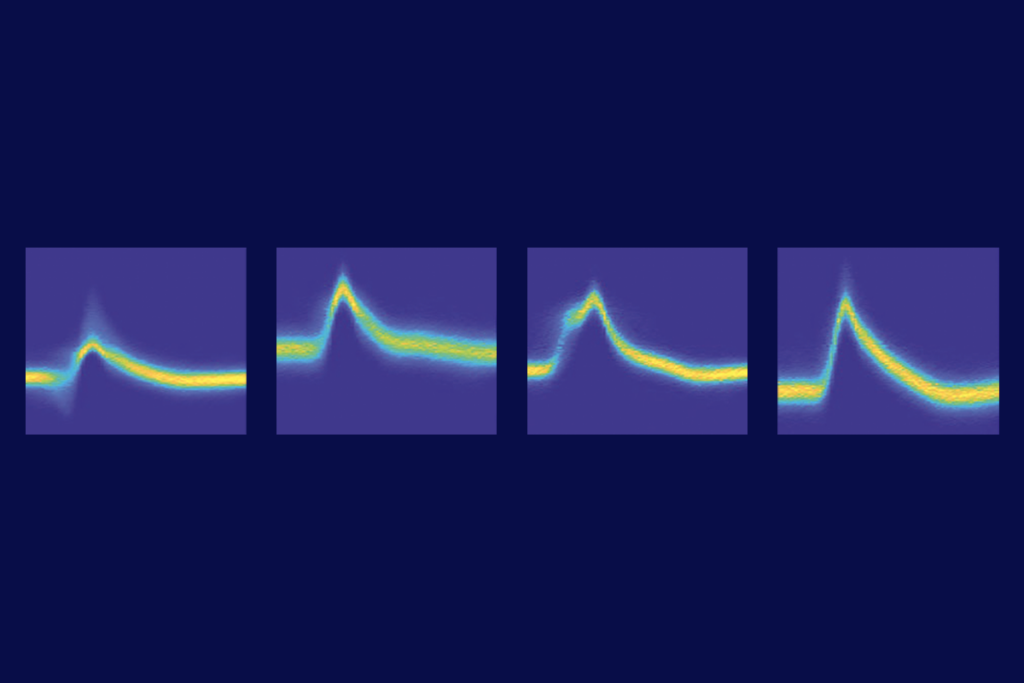

olroyd’s 2002 theory proposed that previously observed changes in dopamine associated with unexpectedly positive or negative results cause neural responses that can be measured with EEG. The more surprising a result, he posited, the larger the response.To test the idea, Holroyd and his colleagues used a gambling-like task in which they told participants the odds of correctly identifying which of four choices would lead to a 10-cent reward. In reality, the reward was random. When participants received no reward, their neural reaction to the negative result was equally strong regardless of which odds they had been given, contradicting the theory.

The result upended the standard view of how the brain learns from feedback, says Gilles Pourtois, professor of psychology and educational sciences at Ghent University and a principal investigator at one of #EEGManyLab’s 13 labs. (The new study’s lead PI, Katharina Paul of the University of Hamburg, did not respond to email requests for comment.) That’s partly why researchers were so eager to see if the result would hold in a larger sample.

In the new paper, participants’ brain responses to the reward—or lack thereof—were largest when the outcome was the most surprising. Beyond clarifying the finding, the work helps set standards for the sample sizes needed to detect subtle effects with EEG, Pourtois says.

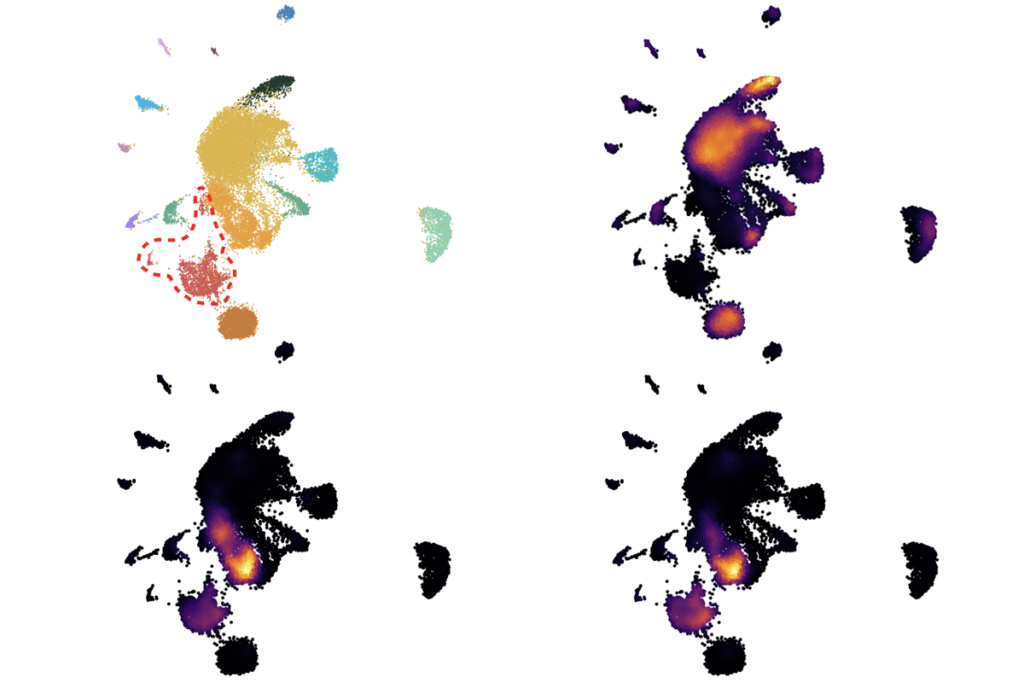

In fact, not all of the 13 labs in the study found a statistically significant effect. It was only when the data were analyzed collectively that the result emerged, says Faisal Mushtaq, professor of cognitive science at the University of Leeds and co-founder of #EEGManyLabs with Pavlov.

“What it demonstrates [is] here is the power of pooling your datasets together to identify these subtle patterns,” he says.

More papers will come from #EEGManyLabs soon, says its co-founder, neuroscientist Yuri Pavlov. Among them is a paper confirming the discovery in 1996 of an electrophysiological marker of attention.