What is the future of organoid and assembloid regulation?

Four experts weigh in on how to establish ethical guardrails for research on the 3D neuron clusters as these models become ever more complex.

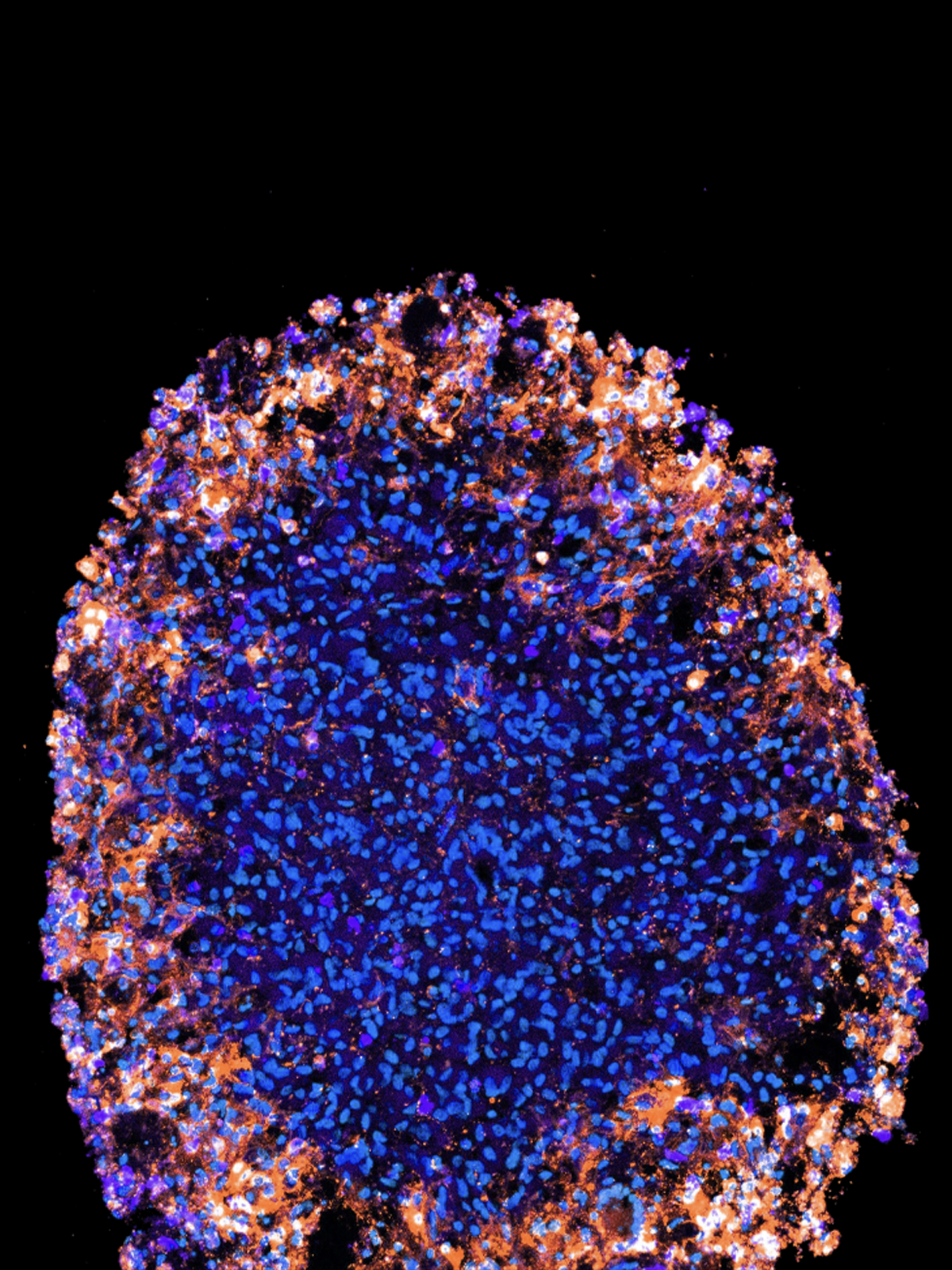

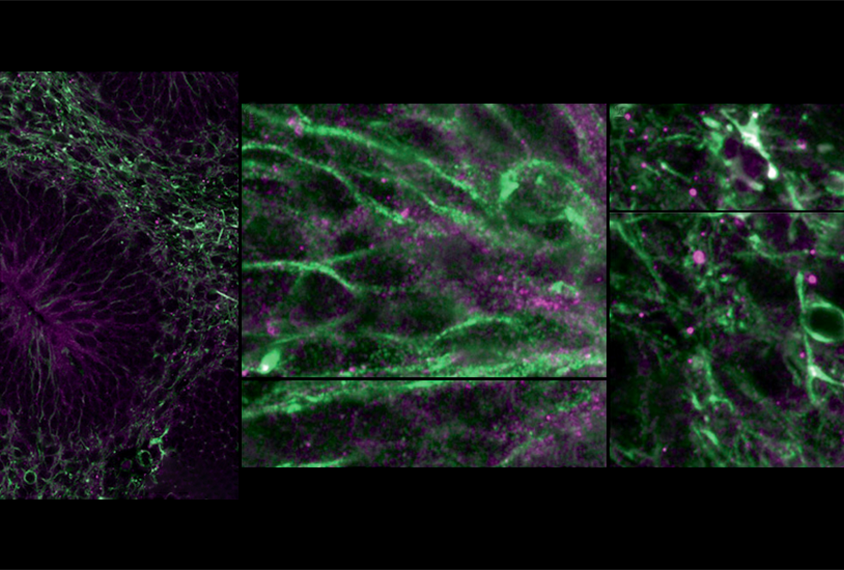

Pacific Grove, California—Neuroscientists have been grappling with the ethics of human brain organoid research since they started growing the 3D neuron clusters a dozen years ago. But calls for ethical oversight of the field are mounting as the models begin to incorporate multiple brain cell types, rudimentary circuits and amalgamations of organoids called assembloids.

Among the concerns cited, donors whose tissues are used to create organoids may not know all the ways their cells could be used as the field advances. And the use of organoids to model pain circuits raises questions about whether these structures could acquire properties related to sensation; similarly, transplanting organoids into lab animals raises questions about whether they could alter behavior and cognition in the animals, or even confer human-like properties.

No evidence to date suggests that any brain organoids sense pain or are conscious, according to the stem cell research guidelines issued in 2021 and updated this year by the International Society for Stem Cell Research. But, the guidelines note, “researchers should be aware of any ethical issues that may arise in the future as organoid models become more complex through long-term maturation or through the assembly of multiple organoids.”

With these issues in mind, a select group of ethicists, neuroscientists, philosophers, patient group representatives, journal editors and others convened last month at the Asilomar conference center near Monterey Bay in California, where 50 years ago experts drew up safety guidelines for DNA recombination. Excited chatter echoed the chirping of the birds outside as attendees debated distinct aspects of organoid regulation, from considering which stakeholders need to be included to how to implement oversight beyond the United States.

No decisions were made, but researchers agreed that organoids and assembloids are still simple enough that no immediate action is necessary—and the meeting was an important first step in shaping future oversight of this research, says attendee Karola Kreitmair, associate professor of medical history and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “I think it’s actually a good time to start to start to think about what kind of bodies could be effective here,” she says.

In light of these discussions, The Transmitter asked Kreitmair and other attendees to reflect on the meeting and what the regulatory landscape of organoid and assembloids research might look like for them. Their responses have been edited for length and clarity.

“I would call for the development of soft regulation with guidelines that outline scientific norms for the field. A scientist would not face a legal problem for violating the guidelines; rather, their colleagues may wonder why they are operating outside of the moral consensus.

Ideally, the guidelines would be issued by an organization such as a government agency, bioethics commission or a scientific society of some sort. The organization could commission research to ensure that the guidelines align with the general public’s values that could be impacted by organoid technology. My guess is that the current speed of the science would require reexamination every three or more years.”

—John Evans, professor of sociology, University of California, San Diego

“The envisioned system should not be a rigid set of laws but an evolving scaffold. It starts with robust local review at the institutional level, supported by clear national regulations with a clear definition of levels of risk, and guided by international organizations, which have the ability to monitor the science, issue white papers and make non-binding recommendations to lawmakers and funding agencies. The most critical component will be maintaining an open, inclusive and ongoing dialogue with the public about what it means to create models to study human diseases with better predictability. It is utterly important that the system be forward-looking, anticipating technical advances (e.g., increased cellular complexity, integration with sensory inputs), and be flexible enough to adapt. It is equally important that limits are set for research aiming to create organoids that may, for example, approach consciousness-like states, possess primitive sensory capacities or experience pain (sentience).”

—Guo-li Ming, professor of neuroscience, University of Pennsylvania

“Many research institutions have existing committees that review locally occurring stem cell research, often called institutional stem cell research oversight committees (ISCROs), which were first established two decades ago with a narrow focus. Since then, many institutions have broadened the scope of ISCRO review, and now some specifically state that they review all neural organoid/assembloid research. Given that this infrastructure of ISCRO committees already exists, and some are already reviewing neural organoid/assembloid research, I think it makes the most practical sense to build upon and bolster the ISCRO system rather than create a new oversight system from scratch. However, not all institutions conducting stem cell research still have ISCROs, and many are under-resourced, so additional resources will need to be invested in the ISCRO system to bring it up to date and ensure there is capacity to review the growing number of research proposals using organoid/assembloid technology.

A second challenge is that, currently, each ISCRO operates as a bit of an island, establishing institutional policies that vary quite a bit from school to school and from state to state. There is not currently any consortium of ISCROs where committee members can gather and share insights, and there is no overarching guidance provided to ISCROs to help them translate guidelines for stem cell research (i.e., the International Society for Stem Cell Research guidelines) into practicable review criteria. I think addressing both of these challenges would go a long way toward bolstering the ISCRO infrastructure in the U.S. and enabling thoughtful, responsive oversight of neural organoid and assembloid research.”

—Kate MacDuffie, assistant professor of pediatrics, University of Washington School of Medicine

“There ought to be an international, standing body that continuously assesses the ethics and can put out guidelines at regular intervals. So, a body that’s doing a little bit more horizon scanning and is alert to what is going on.

At the same time, the field should establish a consortium of nimbler advisory groups that can provide feedback to an institution’s animal care and use committee or to a stem cell research oversight committee in such a way that it’s not just for that specific institution but is at a higher level. Institutions can turn to a higher-level group that can interpret recommendations from the various sources and provide tailored guidance to a particular research project.

Institutions will also often have a research ethics consultation service that thinks through particular ethical questions. At a higher level, there could be four to six groups for the U.S. (each serving a different geographic area) that can apply not only the ethical principles that have been put forth by international organizations, but also local jurisdiction and public perception in that area. Maybe people in Louisiana think differently from people in New York state. Regional services that could assist and advise the individual institutions on specific questions would be a useful thing to aim for.”

—Karola Kreitmair, associate professor of medical history and bioethics, and vice chair of the Hospital Ethics Committee, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Recommended reading

‘Neuroethics: The Implications of Mapping and Changing the Brain,’ an excerpt

Immune molecule alters cellular makeup of human brain organoids

Two primate centers drop ‘primate’ from their name

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Neuroethics: The Implications of Mapping and Changing the Brain,’ an excerpt

Whole-brain, bottom-up neuroscience: The time for it is now