Computational psychiatry needs systems neuroscience

Dissecting different parallel processing streams may help us understand the mechanisms underlying psychiatric symptoms, such as delusions, and unite human and animal research.

“Dr. Halassa, you do not understand, but it is a new system that Elon Musk invented. Starlink … This is what they implanted in me, and I am getting zapped. You need to treat the zapping, not give me these ridiculous medications.”

As a practicing psychiatrist, I must have heard a version of this narrative hundreds of times. Delusions are one of the most common symptoms of schizophrenia, along with hallucinations, disorganized thinking, social withdrawal and flattened affect. Psychiatry has medications that sometimes control hallucinations, but delusions often persist despite treatment.

The idea of a delusion is quite profound; it touches on the very notion of what it is to believe something and how to adjust the belief when the evidence flips. As a systems neuroscientist, when I hear these stories, I cannot help but wonder how they emerge. What type of brain process can possibly make someone believe something with absolute certainty and make it impossible for them to even consider alternative interpretations?

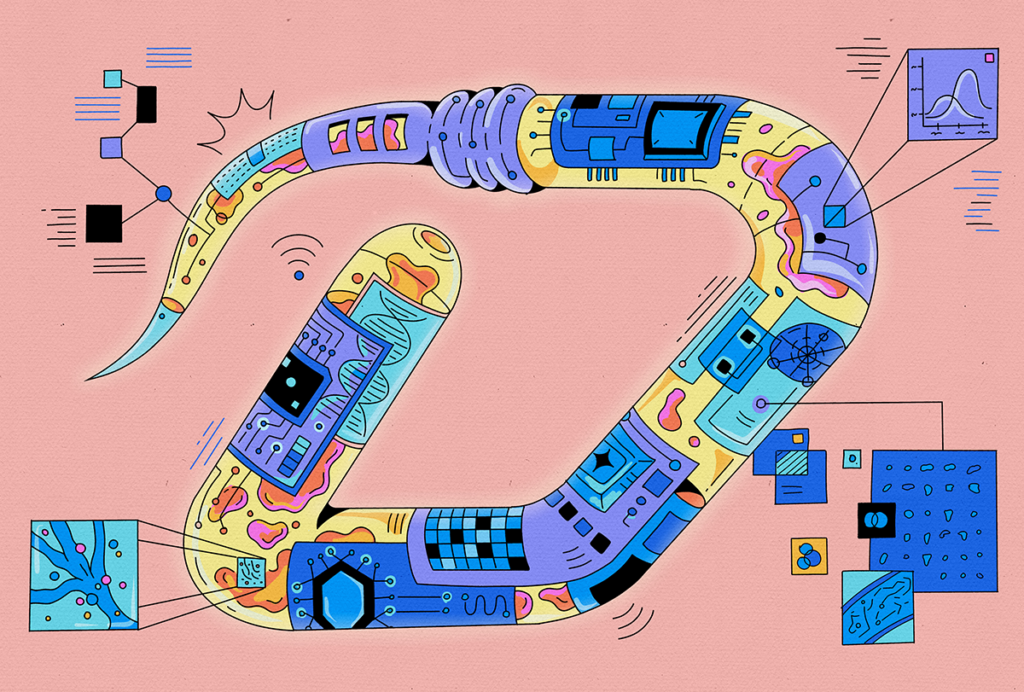

There is good evidence that for any problem, multiple neural systems are running in parallel, regardless of which one is influencing behavior at any one time. But these parallel systems require tight coordination, as well as mechanisms that enable the more reliable system(s) to influence behavior. Schizophrenia is likely a constellation of disorders in which these neural systems are no longer well coordinated. To me, seeing someone in a psychotic state is compelling evidence for this parallel processing framework. Only under these conditions can one appreciate the need for coordination.

Dissecting these different streams may help us understand the mechanisms underlying delusional thinking. What exactly happens to reasoning that allows for someone to hold an implausible belief with such certainty? Is the problem how uncertainty is estimated? How evidence is weighted? How competing memories are managed? Maybe different people have different types of “algorithmic” failures. If so, then wouldn’t they need different therapeutic approaches?

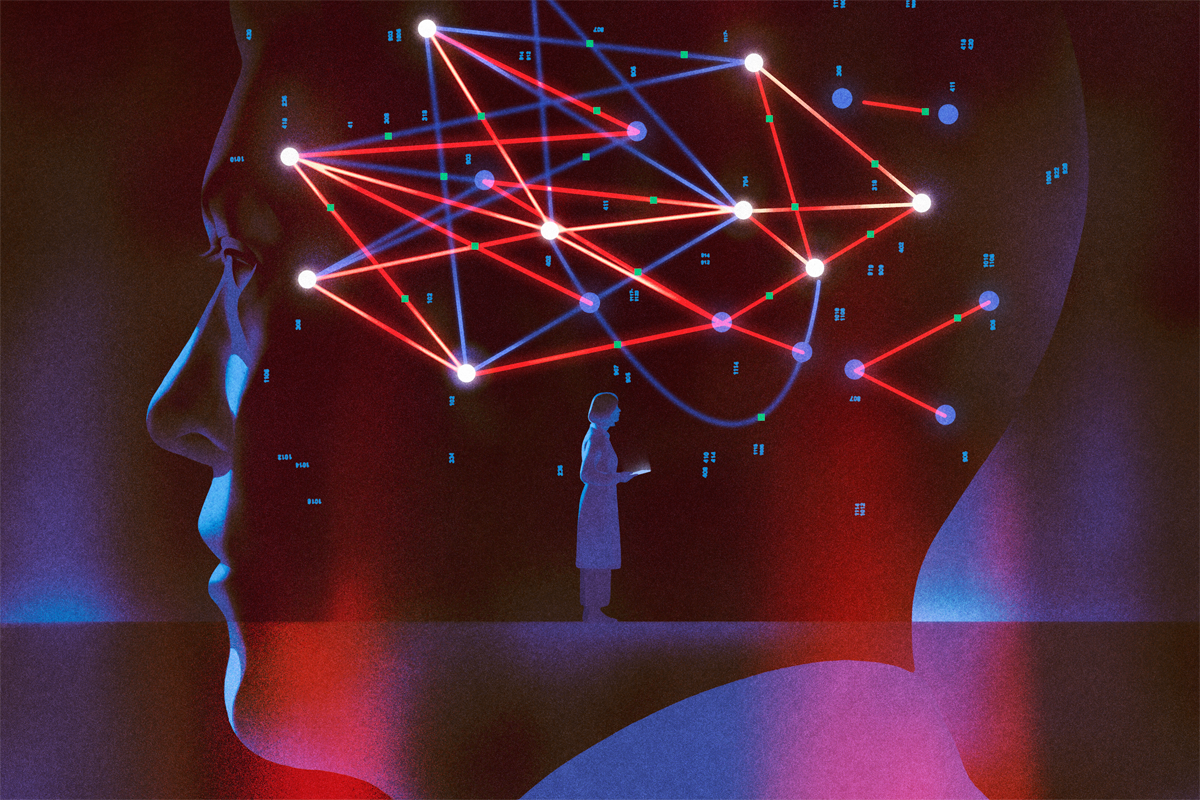

The short answer is that we don’t know. But one promising area of investigation is computational psychiatry, which uses precise behavioral tasks to identify the specific mental operations that have become suboptimal. The approach aims to map these computational changes onto specific brain circuits, creating a bridge between the molecular interventions we have and the behavioral symptoms that people with schizophrenia experience. If you want to know what has gone wrong in someone’s reasoning, you need tasks that isolate specific mental operations and measure them precisely. Computational psychiatry can help to target the algorithmic level where the actual dysfunction lives. However, to target these algorithms, you need knowledge of neural circuitry, and that’s what systems neuroscience does best. In essence, computational psychiatry needs systems neuroscience to make a difference in the real world.

C

Real power emerges when we use the same task structure across species, testing humans, other primates and mice on versions of the same cognitive challenge. Although details may differ, the core computational problem remains constant, enabling us to observe similar neural operations across species, and how they implement different steps of the same algorithm. Crucially, we can do experiments in animals that would be impossible to conduct in humans, such as recording from specific cell types, manipulating their activity and decoding what information they carry. Because the animal is doing something constrained and measurable, we can link what is seen in the brain directly with what the animal computes.

Psychiatric neuroscience was developed outside of this tradition; researchers have tried to use animal models to capture the full mess of real-world symptoms—for instance, forced swim tests supposedly model despair, and elevated plus mazes supposedly model anxiety. But these tasks are too unconstrained, making it impossible to decode what specific computation has gone wrong, because the behavior reflects too many things at once. Human neuroimaging has the opposite problem. Resting-state connectivity can show which brain regions are active together, but it cannot really tell what they are communicating. Both approaches skip over the algorithmic level where the dysfunction driving symptoms live.

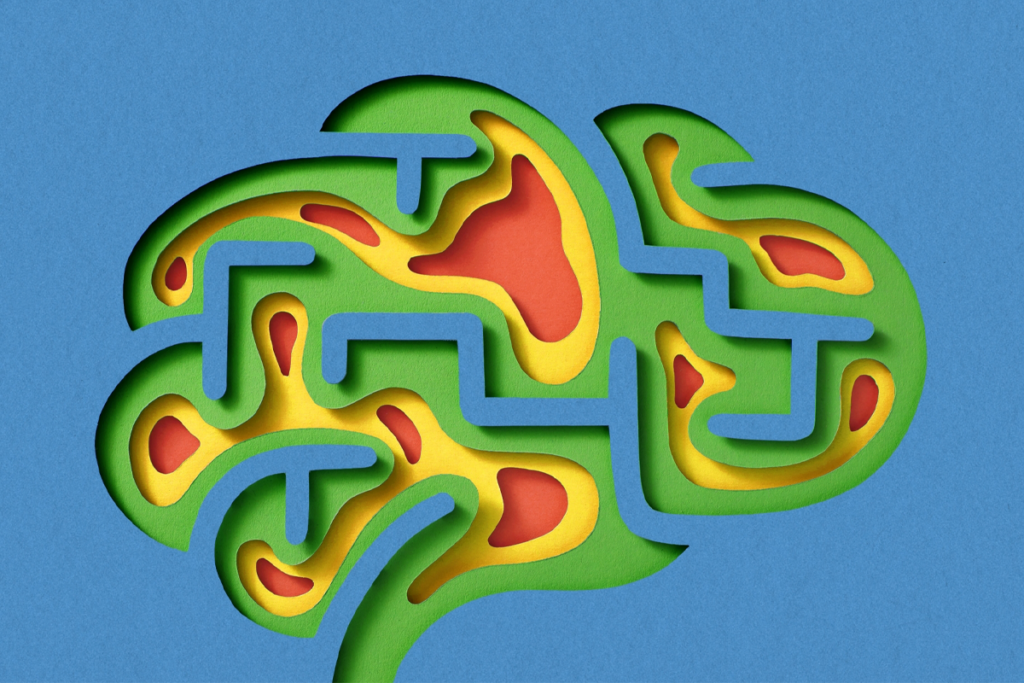

Serendipitously, and using systems neuroscience approaches, my lab stumbled upon a domain in which well-controlled behavioral tasks in animals shed light on a brain-behavior relationship in schizophrenia. Over the past 10 years, we studied how cognitive control is implemented in neural circuits, initially in mice and then in tree shrews. In these tasks, cues guide attention to targets and vary from trial to trial. Research in mice identified how neurons in the prefrontal cortex turn cues into attentional bias signals, which in turn influence processing in sensory circuits.

We discovered that the thalamus is critical for this prefrontal operation. The thalamus is traditionally thought to relay information from the periphery, but our experiments showed that the mediodorsal thalamus is turned inwards, extracting various signals from the vast data within the prefrontal cortex itself. This allows it to identify the right context and help the prefrontal cortex adapt when the context switches. It also identifies the degree of uncertainty in the cues it receives, and we found that it slows prefrontal decision-processing in a manner commensurate with these estimates. In essence, the thalamus provides a natural mechanism for filtering noise in decision-making.

When we developed this approach, we were not studying schizophrenia, but others had shown that people with schizophrenia exhibit altered resting-state functional connectivity between the thalamus and prefrontal cortex. These changes had no behavioral correlates, however. Once we understood what computation the mediodorsal thalamus performs, we could ask whether that same computation might be impaired in people with schizophrenia. Remarkably, we found that those with the disorder are worse at tolerating ambiguous cues—they perform normally when cues are clear but fail disproportionately as uncertainty increases. This behavioral pattern mirrors what we see when we optogenetically inhibit the mediodorsal thalamus in mice performing the same task. The deficit also correlates with thalamocortical resting-state functional connectivity in people with schizophrenia.

So we have convergence: the same behavioral deficit, analogous circuits and similar computational architecture across species. That gives us evidence that we have identified a specific computational alteration in schizophrenia, which opens the door to interventions that target the underlying circuits. Instead of broad pharmacological targeting, maybe we could target the circuits that implement noise filtering and contextual inference.

But that is just one piece. Delusions likely involve multiple computational alterations. How does evidence update beliefs? How is uncertainty represented and used? How does the brain assign credit in complex environments? These might be different changes in different people.

What systems neuroscience can help us do now is build tasks that dissect these operations separately. We have developed tasks in which we ask participants to arbitrate between different forms of uncertainty, including those involving sensory inputs and those involving the structure of the environment or its rules. This allows us to study how people and animals manage uncertainty, identify context and assign credit in naturalistic-like conditions.

Early data from this effort have confirmed our original findings from the simpler task—people with schizophrenia have difficulty managing uncertainty—but are also providing additional insight into the different types of algorithmic failures that people may experience. Identifying which of these fingerprints are most related to the lived experience of delusions is our objective, and we are optimistic that we are closer to realizing this one goal of precision psychiatry.

AI use disclosure

Recommended reading

‘Elusive Cures: Why Neuroscience Hasn’t Solved Brain Disorders—and How We Can Change That,’ an excerpt

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models

Explore more from The Transmitter

Whole-brain, bottom-up neuroscience: The time for it is now

Psychedelics research in rodents has a behavior problem