Autism research at the crossroads

The power struggle between researchers, autistic self-advocates and parents is threatening progress across the field.

I

Wigdor isn’t particularly active on the platform; she mostly retweets, and she has just hundreds of followers, many of whom are geneticists and researchers like her. A handful of them offered admiring comments in replies to her post. But when the paper was published in the peer-reviewed Cell Genomics in June 2022 and she put out a similar 11-tweet thread on 8 June, the response was quite different.

This time, one of the first replies was from an autistic researcher in Australia, who tagged Ann Memmott and pointed to Wigdor’s thread as “a good one for you to dissect.” Memmott, who is autistic, is an associate at the National Development Team for Inclusion in the U.K. and sits on the editorial board of the forthcoming academic journal Neurodiversity. Her Twitter handle identifies her as a “challenger of poor practice in autism research,” and she did indeed dissect Wigdor’s thread, noting for her followers (now more than 28,000), on 12 June, Wigdor’s use of the words “female protective effect” and “risk” and “autism spectrum disorder,” and the description of autistic study participants as male and female “cases.” Memmott, who declined multiple interview requests for this article, also blogged a criticism of the paper.

That helped boost the signal, as did replies and retweets from several other neurodiversity advocates. Then the negative comments came flooding in. The paper was labeled ableist, eugenic, transphobic and intersexist. One person tweeted that Hitler and his army of eugenicist “scientists” would be proud of Wigdor. One called it “shit science.” A few simply gave her some version of “fuck you.”

Monique Botha, who is autistic and uses they/them pronouns, was watching all this. Botha, a research fellow at the University of Surrey in the U.K., has been on the receiving end of some nasty interactions, both in person and on Twitter, and knows how unpleasant it can be. For this reason, Botha did not want to add to the Twitter storm settling over Wigdor. They instead crafted a measured response, mentioning their dislike of Wigdor’s use of the word “cases” but otherwise showing a restraint that can be difficult to maintain, Botha admits, given how exasperating the current state of autism research can be.

The Twitter account @autismsupsoc, however, took a different approach. The account, which “endeavors to raise Autistic Voices & empower Autistic Rights,” has more than 14,000 followers, and it went after the scientists in Wigdor’s timeline. It tagged more than 100 of them in a long thread on 12 June, informing them they were guilty of retweeting Wigdor’s “ableist and bigoted comments” and giving them six days to fix their error. The account said it would update the thread on 18 June (Autistic Pride Day) to “document what action YOU personally took so that history will always remember what YOU did when called upon to correct your mistakes.”

The scientists did nothing, and Wigdor, who also declined to be interviewed for this article, never responded to any of this. By the end of 14 June, the mob had mostly moved on.

C

Also sitting in on the keynote was autism researcher Matthew Belmonte. As Geraldine Dawson of Duke University gave opening remarks about Bourgeron’s work, Arnold began to mutter his displeasure. Pretty soon, other attendees could hear it, and Belmonte could hear it, too.

Finally, Arnold raised his voice and clearly asked Dawson why so much of the research at the conference discussed “autistic subjects and healthy controls,” as if autistic people were diseased. That was enough for Belmonte. He has a brother with autism who is nonspeaking, and Belmonte hoped that genetic research might lead to more insight, and breakthroughs that would benefit people like his brother. Almost before he knew it, Belmonte had stood up. “I’m so tired of hearing this crap,” he snapped at Arnold.

Activity in the room stopped, and heads pivoted to Belmonte. Arnold turned to face him too. He waved his cane at Belmonte.

“You need to listen to autistic people,” he said.

Tensions have bubbled over in conferences ever since. At INSAR, stories circulate about hostile parents berating neurodiversity proponents, and autistic self-advocates shouting at researchers during presentations. There has been enough friction that in 2020, INSAR leadership put in place an official Policy Against Harassment and Discrimination, laying out, among other things, rules against doxing, stalking and disrupting talks or events during the conference.

Evdokia Anagnostou, who is on INSAR’s board and was a keynote speaker at the 2022 annual meeting, admits that it can be somewhat of a relief to put the tensions of that conference behind her. After INSAR last year, she traveled to Italy to attend a Gordon Research Conference on fragile X syndrome and other autism-related conditions. The conference is not well attended by self-advocates, and researchers there were “just taking a deep breath,” she said. It was comforting to know that if a presenter used “the wrong word” it would not be “the end of the world.”

At first glance, the tension is not hard to explain: After decades of exclusion from the decision-making that affected their very lives, some autistic people began fiercely fighting for a seat at the table. But the issue is more complex than just a power struggle, and it’s threatening progress across the field.

F

When the study was published in 2020, Memmott put out a 23-tweet thread, which included statements such as that “it seems” no one on the Yale team cared what happened to the children, and that there was “no mention of ethical oversight.” Her thread was retweeted more than 750 times and quote-retweeted more than 500, and her followers weighed in. One called the study “Nazi-like,” another labeled it “sick child torture,” and a third labeled it “fucking abhorrent.” One account laid out a three-part action plan, calling for identifying the paper’s authors and tagging them in criticisms and protests; informing Yale donors that they were funding child abuse; and notifying the police, because “a crime is still a crime.”

Onward this spun, until Yale and the study leaders put out a statement nine days after the paper was published. The release pointed out that “descriptions of the study have been misinterpreted” and that the study had been cleared by Yale’s institutional review board, adhered to federal ethics guidelines, and obtained signed consent from parents, who could withdraw their children at any time.

Yet autism activism has also stopped studies from even starting. The Spectrum 10K project was announced in August 2021, with a plan to collect the genomes of 10,000 autistic people living in the U.K. (and biological family members, where possible) via saliva sample, as well as request that participants complete a questionnaire. It was launched with considerable fanfare — or propaganda, depending on your viewpoint — and the reaction from the autistic community was immediate. An online petition called “Stop Spectrum 10K” soon appeared on change.org, as well as a “Boycott Spectrum 10K” Facebook page and Twitter account. The hashtag #StopSpectrum10K circulated.

There were some concerns about the study’s lack of transparency around its aims, and worries over conflicts of interest, consent issues and the long-term use of biodata gained from the saliva sample. But the reaction also contained a darker undercurrent. Some commenters said Spectrum 10K would be used for “genocide,” or to “stop autistic people from being born in the future,” or to “wipe out autistics with high support needs.”

Perhaps most troubling for the science community, Memmott singled out researchers associated with the project by name to her followers. Autistic self-advocate Pete Wharmby used a similar tactic, tweeting out a screenshot of the accounts that @Spectrum_10K followed to his thousands of followers.

That summoned the troops. Some researchers associated with the study were targeted in blog posts and Twitter threads that ripped apart their credentials and incorrectly summarized their work. Because the Autism Research Center is part of the University of Cambridge, which is publicly funded, the team and their collaborating National Health Service sites received numerous Freedom of Information Act requests for details of the study, the team’s email exchanges and internal communications.

Spectrum 10K was paused amid this noise, less than three weeks after its initial announcement. An ethics board investigated and asked for modifications, and the study was cleared to resume in May 2022. But the blowback highlighted a larger problem. A researcher from the U.K., who asked not to be identified for fear of being targeted, told me that the singling out of specific researchers around the Spectrum 10K project felt ominous. Watching it, he worried that young scientists would be spooked straight out of the field, and he said he knows “people who’ve either left academia or just gone to study something else” because of the toxic environment around autism research.

Another researcher in the U.K., who also asked that her name be withheld, echoed those statements. She, too, had observed the Spectrum 10K drama and has seen younger researchers consider a “move sideways,” away from the autism field. With Ph.D. students, it’s still “easy” to switch into a field where the dialogue around the research is less vitriolic, she said, “so why wouldn’t you?”

Yet the hostility in autism research is not only aimed at non-autistic researchers. Botha, who has also considered leaving the field, said there have been “quite a few” autistic graduate students, research associates and Ph.D. colleagues who have walked away from their academic dreams because they find the language, literature and environment around autism research to be “traumatic,” and because of hostility from non-autistic researchers.

These young academics “end up sitting in my office, sitting on a Zoom call, crying, having some sort of breakdown and leaving the field,” Botha said. “And the problem is no one talks about it — no one notices.”

Indeed, these days, working in autism research can feel like life on the other side of the picket line, for autistic and non-autistic alike. Brian Boyd, professor of education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, has been thinking about the current environment, too. He was at the Autism-Europe International Congress in October 2022 in Cracow, Poland, where an attendee repeatedly told presenters during the Q&As that his autistic child has not benefited from their kind of research. The fact that this attendee made his speech during multiple sessions, including keynotes, made it seem more like an agenda than a spontaneous statement, and it set a tense tone for the meeting. Boyd knows that younger researchers want to “figure out how to partner with autistic stakeholders,” but he worries that tense audiences like this and online bullying may keep early-career researchers from getting into the autism space “because they’re afraid of being canceled.”

“You make one mistake,” he said, “and all of a sudden, your name is thrown out there, and you’re the worst person in the world.”

A

It was his aggression that led the family to bring Jonah to the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, Maryland. He went in at age 9 and stayed for nearly a year. His behavior was initially improved when he came home, but it wasn’t until he began regular electroconvulsive therapy at age 11 that he truly began to stabilize, Lutz said. And although Jonah still sometimes hits himself or bites his hand when he’s upset, this is a “tiny fraction” of the harmful behavior he used to exhibit.

But he still lacks “safety awareness,” Lutz said. When Jonah was 16, the family tried, for once, to have a proper vacation: a cruise. The trip began in Baltimore, but the ship had barely left port before Lutz realized they had miscalculated. As the family walked around the top deck, with Lutz explaining to Jonah parts of the ship and their plans for the week, he noted the water — the Atlantic — all around them.

“Swimming,” he said.

“No, no,” his parents told him and pointed to the still-unfilled pools. “We can swim in those when they’re ready.”

A few minutes later, he simply made a break for the railing. Lutz’s husband had to take him out with “a flying football tackle,” she said. The rest of the trip was constant surveillance to keep Jonah from going overboard. “You’re never very far from a railing on a cruise ship,” Lutz said.

Jonah is 24 now. He will almost assuredly need a caregiver for the rest of his days. Lutz herself has already dedicated her personal and professional life to him. She has a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania, in the history and sociology of science, and is a founding board member of the National Council on Severe Autism. She would like an official way to differentiate Jonah, his needs and his experiences, from the autistic people who are less, or differently, affected by their autism. So when the Lancet Commission on the Future of Care and Clinical Research in Autism report was released online in December 2021, Lutz felt a flash of hope.

The 53-page report was chaired by Catherine Lord and Tony Charman, and it included another 30 co-authors. It aimed to investigate how best to meet the needs of autistic people and families around the world in the next five years, was put together by stakeholders on six continents and included perspectives from clinicians, health-care providers, researchers, parents, advocates and self-advocates. Among its many recommendations, it suggested that “profound autism” be used as an “administrative term” for autistic people who need 24-hour access to an adult if concern arises, are unable to be left alone in a residence and cannot take care of “daily adaptive needs.” The commission acknowledged these people would likely have an IQ below 50 or “limited language,” or both, thereby defining profound autism by intellectual or language disability, and it estimated that this description would fit between 18 and 48 percent of the autistic population worldwide.

Those people would look a lot like Jonah, and this seemed like progress to Lutz. She tweeted about the report, calling it “big, big news.”

Her tweet was met with pushback from more than two dozen Twitter accounts that proclaimed an autistic identity. And there was broader pushback against the report itself, too. Within two months of the Lancet report’s online publication, the Global Autistic Task Force on Autism Research — some two dozen autistic groups from around the world — published an open letter to the commission, criticizing (among other things) the proposed use of the term profound autism, calling it “highly problematic.” Then, in September, Elizabeth Pellicano and her colleagues published a paper titled “A capabilities approach to understanding and supporting autistic adulthood,” writing that although some “have called for the creation of a separate ‘profound’ or ‘severe autism’ diagnostic category for those with the most severe impairments,” the authors felt the label would “potentially exclude” a swath of autistic people from “the concern, dignity and respect offered to others.”

Self-advocates and others lauded Pellicano’s work; her tweet on the paper received more than 1,600 likes. But for Lutz, it feels like every step forward is met with this kind of resistance, and that can be maddening. She is sure the neurodiversity movement is biased in favor of its own “high-functioning” membership, she said, and is willfully ignoring the reality of people such as Jonah and families such as hers. The autistic self-advocates who are dominating the conversations online think they “know what it is to be like Jonah” she told me, “but they don’t, because they were never severe.”

What Lutz is complaining about is called partial representation, a term used to describe a group — political, social, whatever — that purports to speak for the entirety of its members but fails to do so. Lutz co-wrote a 2020 paper on this topic with Matthew McCoy, who teaches medical ethics at the University of Pennsylvania. They defined partial representation as an actor claiming “to represent a particular group of people, but appropriately engages with only a subset in that group.”

Partial representation might be seen as far back as the birth of the neurodiversity movement. In 1993, at the International Conference on Autism in Toronto, Canada, an autistic person named Jim Sinclair took the stage to deliver a presentation. Sinclair’s speech, titled, “Don’t mourn for us,” is often credited with kicking off today’s self-advocacy movement. The speech began with the statement that “parents often report that learning their child is autistic was the most traumatic thing that ever happened to them,” and Sinclair went on to describe the “grief” parents felt as the loss of “the normal child” they hoped for but who “never came into existence.”

Yet a child did come into existence — an autistic one — Sinclair said, reminding the audience that that child is “here waiting for you.”

It was a watershed moment, and in the nearly 30 years since that conference, the neurodiversity movement has swelled. But if there is a fly in the ointment of that speech, it is the reality that some autistic people lack even basic verbal communication skills, never mind the gift for prose Sinclair showcased while addressing a crowd and speaking about “us.”

McCoy said that to avoid partial representation in autism, a group would need to interact with those who are able to articulate their own interests, but also those with the “most profound autism” and “patients and caregivers,” as well as doctors and others. If a group relies solely on “engagement with autistic self-advocates to understand the interests of the broader autistic population,” then it “carries a risk of bias,” the paper states.

The paper also suggests that partial representation has long been a part of the broader autism community. “At least in its early days, Autism Speaks failed to engage appropriately with autistic self-advocates,” the authors wrote, “while ASAN [the Autistic Self Advocacy Network] has failed to engage appropriately with parents raising concerns on behalf of their children.”

Z

The day is meant to commemorate people with disabilities who were killed by a parent or other household member through direct action — or sometimes inaction, such as neglect. The group behind it has archived hundreds of names, going back as far as 1980. The event that spurred the founding occurred on 6 March 2012, when a woman named Elizabeth Hodgins, in Sunnyvale, California, shot her autistic son George, 22 years old at the time, and then committed suicide herself. The husband came home to find the bodies.

This of course made the local news, and given that the mother was already dead, reporters tread lightly, carefully avoiding blame as they tried to explain how such a horrific thing could have happened. Newspapers relayed that George was “low functioning and high maintenance,” and had limited use of language. Reporters wrote that he had formerly gone to an autism center but for a few months had been at home full time, often alone with his mother. Neighbors speculated that Hodgins was exhausted from this new, constant caregiving, and that she’d had a nervous breakdown.

Yet no one interviewed an autistic person. If they had — if they had spoken to Gross, for instance — they would have gotten a different view of things. They would have heard that the tragedy here was not that George was autistic, as the reporters seemed to suggest, but that he was murdered. They would have heard that George’s disability did not somehow make that murder more acceptable. And they would have heard that George’s death would be mourned by those who knew and loved him, that his life had value.

That line of thinking was nowhere in the media coverage. And it is exactly this kind of blindness from the mainstream majority that makes self-advocates as tenacious as they are. For decades in the medical arena, autistic people have been studied “in an extractive way,” Gross said. Scientists asked for genetic material, or a brain donation upon death, but wanted no input from autistic people on what to “do with those things.” The relationship was all take and no give.

This imbalance is partly what drew Gross into advocacy. ASAN has worked forcefully, often collaboratively, for change in the world of autism. The group has official positions on applied behavior analysis (ABA), genetic research and discrimination in health care, among many other areas, but ASAN understands that a key to advocacy is compromise, and that toxic behavior makes it easy for policymakers to ignore you.

So it is not ASAN that is comparing autism researchers to Nazis. That comes from legions of individual Twitter handles, Facebook accounts and online warriors whose power lies in their outraged tone and sheer volume. Many of these people are young, autistic and not particularly interested in hearing the nuances around scientific terminology or explanations on why all genetics is not eugenics. They have gathered online to fight against a world they feel has callously swept them aside for decades, and that sometimes includes non-autistic trolls and the parents of autistic children.

With good reason, for autistic self-advocates have countless moments in history to point to: the Willowbrook scandal; the use of “aversives” in ABA therapy; the ties between autism research and eugenics. Given that these things occurred within the past century, autistic self-advocates are correct in continuing to sound the alarm, said Ari Ne’eman, disability activist and ASAN co-founder. And anyway, there are technological advances today that need careful scrutiny. It’s possible there could be a prenatal test that “speaks to probabilities” for autism, he said, which could lead parents to abort autistic children. And, he said, if one considers the possible use of CRISPR technology to modify heritable genetic conditions, then the concerns of autistic people around eugenics are “legitimate.”

Autistic people and advocates are also keenly aware of where true power lies, and it’s not on Twitter. Shannon Des Roches Rosa is senior editor of Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism, a neurodiversity advocate and the parent of an autistic child. She said it is the biomedical community and its funders who hold the key to the future of autism research, leaving the “disenfranchised” autistic community with just its voice. It is unreasonable to expect that the voice will always be diplomatic, especially given that autism can be considered a social disability. “And sometimes,” she said, that voice will “come out as bullying. Because what other power do they have? I mean, they’re furious. But that doesn’t mean they’re wrong.”

Often what they are furious about boils down to money. Ne’eman said that the greatest return on investment for autistic people comes from services and quality-of-life studies, and those areas are “dramatically underfunded.” Indeed, the greatest portion (44 percent) of autism research dollars in 2018 went to questions around the biological aspects of autism, as tabulated by the U.S. Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee. The second-largest portion (about 20 percent) was “risk factors,” which encompasses both genetic and environmental concerns. That is more than 60 percent of funding dedicated to the causes of autism. Meanwhile, services and lifespan issues were allotted just 6 percent and 3 percent of funding, respectively.

Perhaps most angering for neurodiversity advocates, there has been little change in the pie portions over time. In 2008, 55 percent of autism research funding ($123 million) was pointed at risk factors and biology questions, whereas only 6 percent ($11.5 million) went to services and questions around the lifespan of autistic people. After a decade of shouting from neurodiversity activists, 63 percent of funding ($247 million) in 2018 went to risk factors and biology, but services and lifespan issues had moved to just 9 percent ($36 million).

Much of this imbalance comes from the existence of specific funders such as the Simons Foundation (of which Spectrum is a part, though editorially independent). The Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative gave out more than $44 million in grants in 2021, aimed solely at understanding, diagnosing and treating autism. Neurodiversity advocates would like to see more going toward services and quality-of-life issues, but the portions of the pie are unlikely to change unless the U.S. government increases its funding or organizations such as the Simons Foundation reimagine their mission.

Y

Damian Milton is autistic, a senior lecturer in intellectual and developmental disabilities at the University of Kent in the U.K., and a consultant to the National Autistic Society. He’s also the father of more than one neurodivergent child. He is outspoken and active on Twitter, and for these reasons has faced his share of criticism — even from neurodiversity advocates, some of whom find him “not activist enough,” he said.

But he’s maybe best known for his paper on the double empathy problem, published in 2012. It has become a central tenet in thinking about how autistic people interact with the rest of the world. The paper states that whereas autism is often “defined as a deficit in ‘theory of mind’ and social interaction,” the double empathy problem posits that the communication and social difficulties of autistic people are “a question of reciprocity and mutuality.”

Milton wrote that although “it is true that autistic people often lack insight into [neurotypical] perceptions and culture,” it is “equally the case that [neurotypical] people lack insight into the minds and culture” of autistic people.

Neither group truly understands each other, he told me, and both cultures are more at home interacting with people like themselves.

He thinks this dual misunderstanding is partially responsible for tensions in the broader autism community. These two groups have “a totally different set of experiences and way of making meaning from those experiences,” he said, and added that “what’s bullying to one person is righteous anger to another.”

Miscommunication caused by the double empathy problem makes de-escalation harder. But so can the nature of autism itself. As Des Roches Rosa pointed out, autism is categorized as a social disability. And researchers have long suggested that inflexible thinking is a component of it. They are loath to point that out publicly when discussing today’s tensions, but some suspect that the logjam in dialogue has something to do with the characteristics of autism.

But there is another theory, too. Both sides openly acknowledge the online bullying. Yet neurodiversity leaders and social-media accounts with large followings have done little to curb it. That might be partially because muffling the anger seems pointless. Botha doesn’t believe “there is a tone that will particularly be accepted.” Autistic people are forever dismissed as too angry, too irrational, biased — easy excuses researchers use to “discount what autistic people are saying,” Botha said. So what is the point of trying for a more acceptable way of speaking? It won’t matter.

I

Yet Milton believes a good first step toward better relations would be requiring young researchers to be trained on language use. If principal investigators are sending their Ph.D. students out to recruit participants or present work without knowledge of the current controversies or language sensitivities, then they are “setting that student up for quite a traumatic experience,” he said.

Experienced researchers agree with this. Anagnostou said it is up to the lead investigators and lab leaders to educate neophytes on language, what the current controversies are and what to expect from conference audiences. “As senior people, we owe our young people a little bit of a more sophisticated conversation about the implications of their work,” she said. It isn’t fair for young scientists to arrive at a conference and not know that neurodiversity advocates might shout from the audience or that “there are different points of view” about the words used in scientific presentations.

If these younger researchers were better educated, that could take some of the sting out of the room. Mostly, however, the feeling is that autism research is caught up in a moment, and the tension isn’t going to go away any time soon.

Boyd, the University of North Carolina researcher, is non-autistic. But he’s also a gay Black man, and he’s more than familiar with the ways in which minority communities fight oppression. He knows that without upheaval, nothing changes. “We’re going through a disability rights movement in autism,” he told me. “And I think those of us who are neurotypical are going to have to do a little bit of acceptance that we’re going to feel uncomfortable in this space right now. Because there’s a marginalized group who’s asking, rightfully, for their voice to be heard.”

In social and political movements, activists have a range of tools at their disposal. Collaboration is one, and groups like ASAN have used this to great effect. Confrontation is another tool. Social media has been a boon to communities of all kinds, including to the neurodiversity movement, but it has also made confrontation an easy tool to deploy. For some advocates, it can be as quick and simple as logging on, “metaphorically throwing rocks” for the cause, and then logging off, Gross said.

But the problem is that confrontation sometimes fails in the long run. As a tool, it operates as a kind of hammer: good for smashing things and getting attention, but not for winning hearts and minds. In their article “The paradox of victory: Social movement fields, adverse outcomes, and social movement success,” Bert Useem and Jack Goldstone wrote that if a group’s actions “polarize the social movement field,” then even initial successes are unlikely to last. Enduring success, they wrote, comes from gaining support from “a variety” of people in the social-movement field, thereby creating a “stable new consensus among multiple key actors.”

Right now, the autism field feels far from a broad consensus, and collaboration might seem in short supply. Especially on social media, the hammer rules the day. Yet even Anagnostou, who has been criticized online herself, can understand this. She knows that many autistic people have been living difficult lives in a neurotypical world for a long time. She knows they are sick of it. And she knows self-advocates play a critical role in driving change.

“So I’m OK with the hammer,” she told me. But those wielding it need to know its limitations. “The minute you equate my work with Nazis, it is very hard — as much as I try to see that position with respect — not to feel personally attacked,” she said. Accusations like that are not made in good faith, nor do they recognize her years of service to a needful population, and without at least that modicum of truth about her life and her efforts, in those moments of feeling attacked it leaves her unwilling to engage in conversation.

The end result is more polarization, a halting of progress and a decrease in collaboration. For those reaching into the toolbox for the hammer, she said, “we need to be clear that that is not moving us forward.”

Divisions over ABA

But legions of autistic people and neurodiversity advocates are dead set against it. ASAN’s public stance, for instance, is that ABA and similar therapies can “hurt” autistic people, and “don’t teach us the skills we actually need to navigate the world.” Online, there are scores of people — autistic or otherwise — calling ABA traumatic, torture, bigoted, a “shitshow.”

Much of their dislike is tied to precedence. Up until the 1990s, ABA used “aversives” to stop aggressive or harmful behavior, including loud sounds, slaps or even electric shocks (the Judge Rotenberg Center in Canton, Massachusetts, still uses shocks). Yet in online autism groups, members sometimes pass around memes as if they are facts, or say that ABA tries to “convert autistic people into neurotypical.” It can feel impossible to productively discuss this topic, as many Facebook autism groups run by neurodiversity advocates prevent dialogue on ABA by banning positive comments in their forums. “Autism Inclusivity” has more than 145,000 members and has a “no pro ABA” post guideline; the groups “Sounds autistic, I’m in” and “Autistic Adults with ADHD” have similar guidelines.

Battling against misinformation and the ranks of people who disapprove of the therapy has sapped the strength of some ABA practitioners. Yev Veverka, a board-certified behavior analyst (BCBA) who has a daughter with autism, said “a lot” of her colleagues “have left, or are talking about leaving.” The reason the rest have stayed “is because we have these meetings” and look around and “are like, ‘What if we all go? Then what?’ So it’s like this sense of obligation, almost, to the field.”

Armando Bernal, a BCBA with autism, is also struggling with the rigidity of the anti-ABA community, because he knows its principles can be effective. When Bernal was diagnosed with autism at age 3, the doctor told his mother to focus on teaching him sign language, because he would never speak. This was in the 1990s, when there was no mandated insurance coverage for ABA, and Bernal “didn’t grow up with a lot of money,” he said, so his mother went to the public library and checked out books on autism to craft her own strategies for helping her son.

Armando started in a special-education preschool, but he eventually tested into general public schools and went on to higher education — first college and then an online course that earned him certification as a special-education teacher.

Still, he felt he could do more. When he learned about ABA, the science reminded him of the techniques his mother had used to help him blossom. He went to graduate school and in August 2019 became a BCBA. He’s now clinical director of an ABA program, consults with parents and speaks at colleges, and is associated with Vanderbilt University’s TRIAD Institute, where he encourages self-advocacy in people with autism.

He considers himself an “interesting bridge” between communities. Half the people he meets (mostly non-autistic) tell him he’s an inspiration. The other half, often autistic, ask him, “How could you ever be a part of that?”

Bernal fully understands the doubters. He knows the history of hitting, and electric shocks that were used as deterrents. But he also knows the application of the science has changed, and he knows that it helped him. And it bothers him that there does not seem to be room for discussion.

“Don’t get me wrong,” he said, if ABA detractors “are saying that they have gone through some sort of traumatic experience, they need to be honored and respected. But for you to shut down a whole science? I feel that is difficult.” What the field needs, he said, is “an open dialogue.”

When Bernal was young, he was sometimes ridiculed for his autism, and he became ashamed of it. He knows there is less stigma attached to being neurodivergent now. He recently interviewed a man in his 60s, newly diagnosed as autistic. The man had been considered strange his entire life, he told Bernal, and had lived like an outsider. Talking to him, Bernal had a moment of realization. Given his own socioeconomic status as a boy, if Bernal had been of the same era as this man, he would have remained undiagnosed and dismissed as unreachable, he said. It’s likely he would have ended up “in an institution or a jail or on the streets if my family couldn’t take care of me.”

So Bernal knows there has been progress. Yet the current state of dialogue on the autism field has him worried. If the varying factions in autism cannot communicate in a “professional way,” he said, then things “will plateau and stop.”

“We’re in this limbo,” he said. “We’re not moving forward or backward; we’re just butting heads.”

Return to main article

Correction

Recommended reading

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

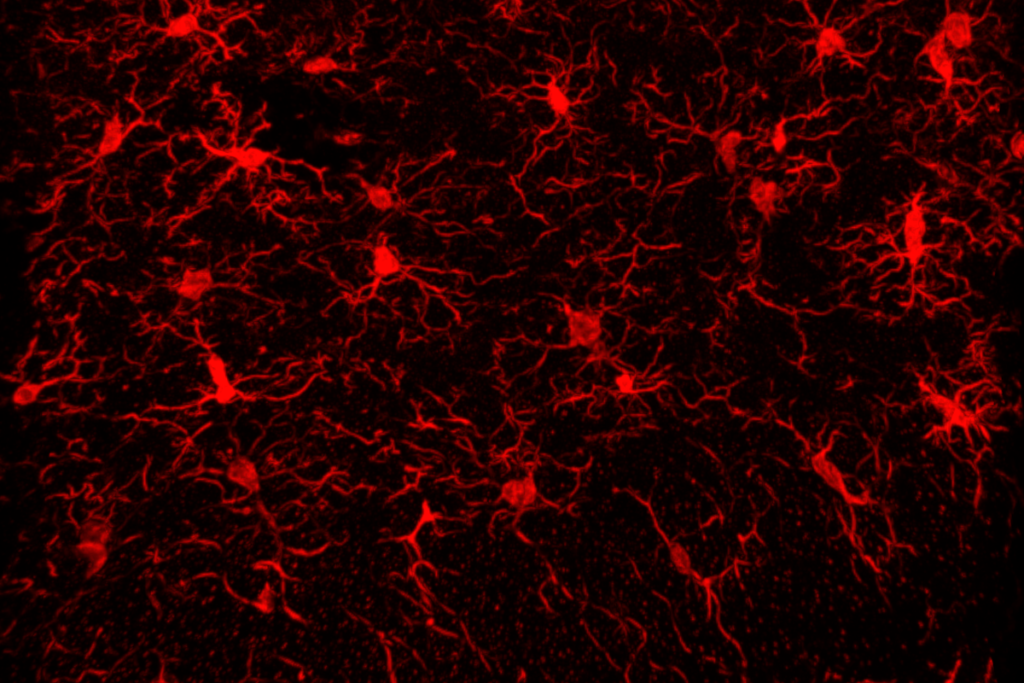

Microglia implicated in infantile amnesia

Explore more from The Transmitter

This paper changed my life: Ishmail Abdus-Saboor on balancing the study of pain and pleasure