How to get children with autism to sleep

Insomnia troubles many children with autism. Luckily, research is awakening parents to some simple bedtime solutions.

W

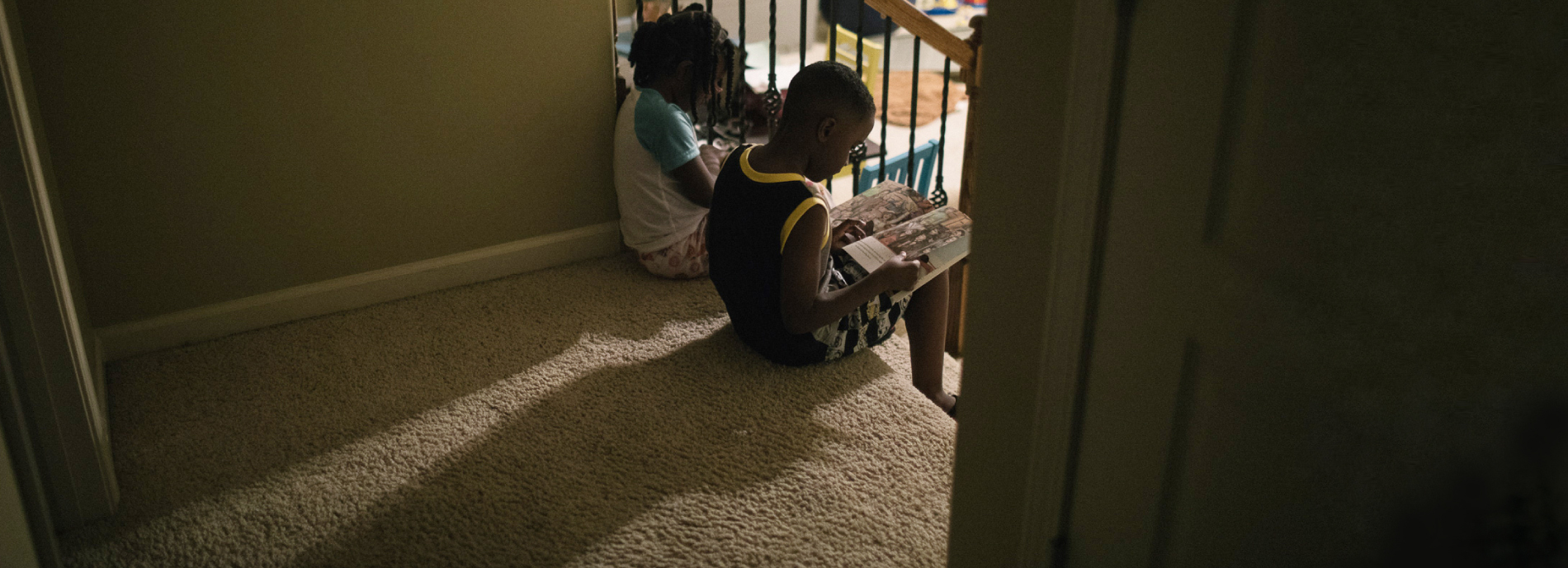

hen Nick was a toddler, he struggled to make sense of language, coordinate his own limbs and orient himself in the world. His mother, Brigid Day, got some sympathetic advice from his neurologist. It was permission, essentially, to soothe her child into sleep by lying next to him in bed. “His pediatric neurologist even said, ‘That is something you can do to make his life calm and easy for him when a lot of things are hard,’” Day says. Nick had multiple delays — in crawling, walking, pointing, speaking — and at age 4, he was diagnosed as being on the autism spectrum.The nightly ritual worked well, Day says, but eventually it got old. Nick usually took less than 15 minutes to nod off, but he sometimes remained awake for an hour. “I would be very frustrated,” says Day, who lives in Brentwood, Tennessee. Many nights, she would fall asleep in her son’s bed. On others, she would quietly get up, steal an hour or two for herself and then settle down in the downstairs bedroom she shares with her husband Mike. On such nights, though, between 1 and 3 a.m., she would inevitably hear Nick call. Because of his weak balance and motor skills, she didn’t want him negotiating the stairs in the dark, so up she would go to get back into his bed and reassure him. A soft-spoken woman who seems deeply in sync with her child, Day felt torn between addressing his needs and meeting her own. As Nick’s 10th birthday approached last year, she became increasingly convinced that something had to change. “It was disrupting my life,” she says.

Jaxon Tyler’s parents also spent years in a state of perpetual fatigue, wrestling with a different set of sleep problems. From the time he was a toddler, Jaxon, now a bright, energetic 7-year-old with mild features of autism, could take as much as an hour to fall asleep and then seemed to have no idea when nighttime was over. He would sometimes awaken his parents at 3 a.m. to ask if it was time to get up. Bedwetting was also an issue; his parents would wake him every night at around 10 p.m. to take him to the bathroom. Even so, they had to change his sheets about one night a week.

As far as parental exhaustion was concerned, “it was an 8, 9 or 10 on a scale of 1 to 10,” says Jaxon’s mother, Dawartha Tyler, who lives in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. “By the time we’d finally get him back down and settled again, it basically would be time to get up and start the day.”

At least half of children with autism struggle to fall or stay asleep, and parent surveys suggest the figure may exceed 80 percent. For typical children, the figures range from 1 to 16 percent, depending in part on how insomnia is defined. The precise nature of the problem varies from child to child, but the consequences are fairly universal. For parents and caregivers, sleep issues deepen the stresses they may already feel managing the needs of a child on the spectrum on top of life’s other demands.

For the child, sleep problems can make everything else more difficult, night and day. Poor-quality sleep may exacerbate many of the challenging behaviors associated with autism, such as hyperactivity, compulsions and rituals, inattention and physical aggressiveness. A study of 81 children with autism last year strongly linked waking up in the night to acting out during the day. Another study found that sleep problems in children with autism are among the strongest predictors of hospitalization. And yet another study last month linked sleep disturbances to extreme autism traits in children at the severe end of the spectrum.

Despite the toll it takes, sleep trouble was a somnolent research area until the past decade or so. Part of the issue for scientists has been how to study it. Researchers have relied mainly on parent reports, rather than on more objective measures, such as actigraphy, to determine the prevalence and nature of sleep issues associated with autism. Polysomnography — the ‘gold standard’ for some types of sleep studies — is difficult to conduct in children with autism. Those children who can tolerate spending a night or two in a sleep lab with a variety of sensors on their face and chest may be on the milder end of the spectrum to begin with, a selection bias that can skew results. Sleep research in autism is just beginning to benefit from the sort of rigorous methodology it needs, says Ruth O’Hara, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University in California. O’Hara has developed techniques to make polysomnography more bearable for children on the spectrum.

There is another reason for the field’s sleepy start: Compared with other features of autism, such as difficulties with language or behavior, insomnia can seem less urgent, says Beth Malow, professor of neurology and pediatrics at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. Malow led a sleep study involving more than 1,500 children with autism ages 4 to 10. She says she was surprised to find that although fully 71 percent of the children had difficulty sleeping — according to a standardized assessment completed by their parents — only 30 percent had received a diagnosis for any kind of sleep-related problem. And less than half of those children were prescribed any kind of medication.

“The pediatricians are just swamped,” Malow says. They have to prioritize many things, including the child’s behavior, how she is doing in school or how her language is developing. And yet, Malow says, “it may very well be that if the child is sleeping better, [she is] going to do better in terms of learning and behavior.”

A decent night’s sleep is not an impossible dream for most children with autism. The first step is to manage any pressing medical problems, such as sleep apnea or seizures. After that, basic, consistently applied changes in the child’s routine to encourage more physical activity during the day and less stimulation at night can make a huge difference. Malow is a leading proponent of this approach and has been studying efficient ways of spreading this kind of “sleep education” to families in her region.

“It’s really the low-hanging fruit,” says O’Hara, who, like Malow, is trying to expand access to sleep education in her local area. “There’s a lot we could be doing to tell parents how to implement some very simple and straightforward behavioral modifications.”

A huge need:

W

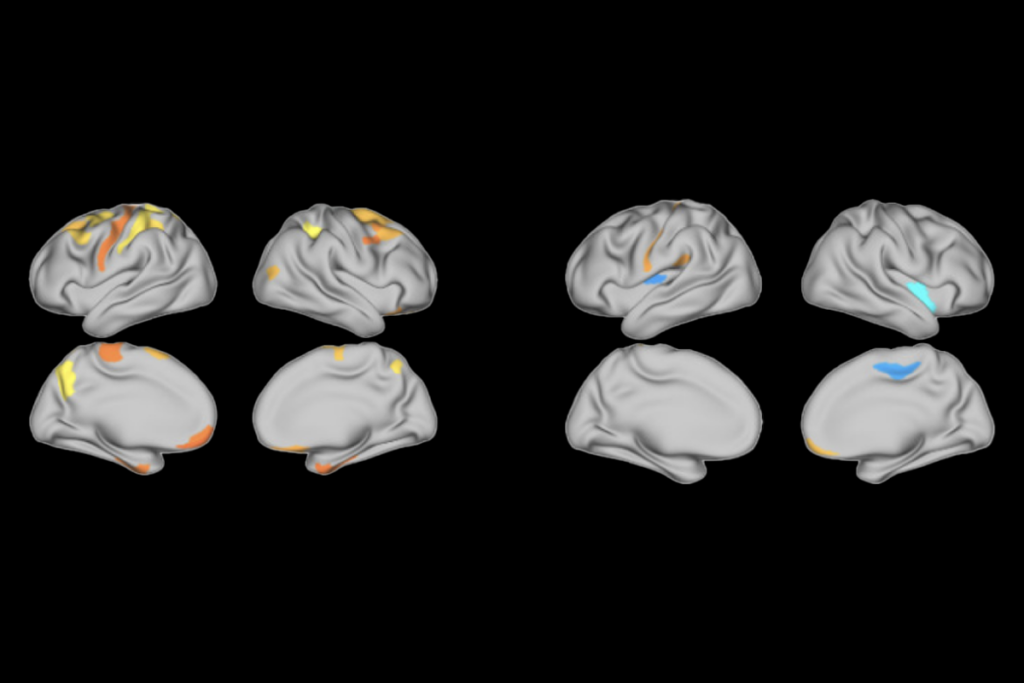

hy people with autism struggle with sleep issues is poorly understood. Chances are that these particular challenges converge from many biological directions, just like autism itself. Many of the medical problems that commonly trouble people on the spectrum may play a role: Anxiety disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), gastrointestinal distress and seizures can directly interfere with sleep or may require medications that disrupt sleep. ADHD stimulant drugs, for instance, commonly cause insomnia. And many psychotropic drugs can cause daytime sleepiness that harms the quality of nighttime rest.Some researchers point to evidence that children with autism tend to be in a heightened state of physiological arousal. For example, many have increased sensory and gastrointestinal sensitivities, elevated levels of anxiety and even — according to a few studies — faster-than-average heart rates while sleeping and while awake. “Hyperarousal can be a contributor to poor sleep in this population,” Malow says.

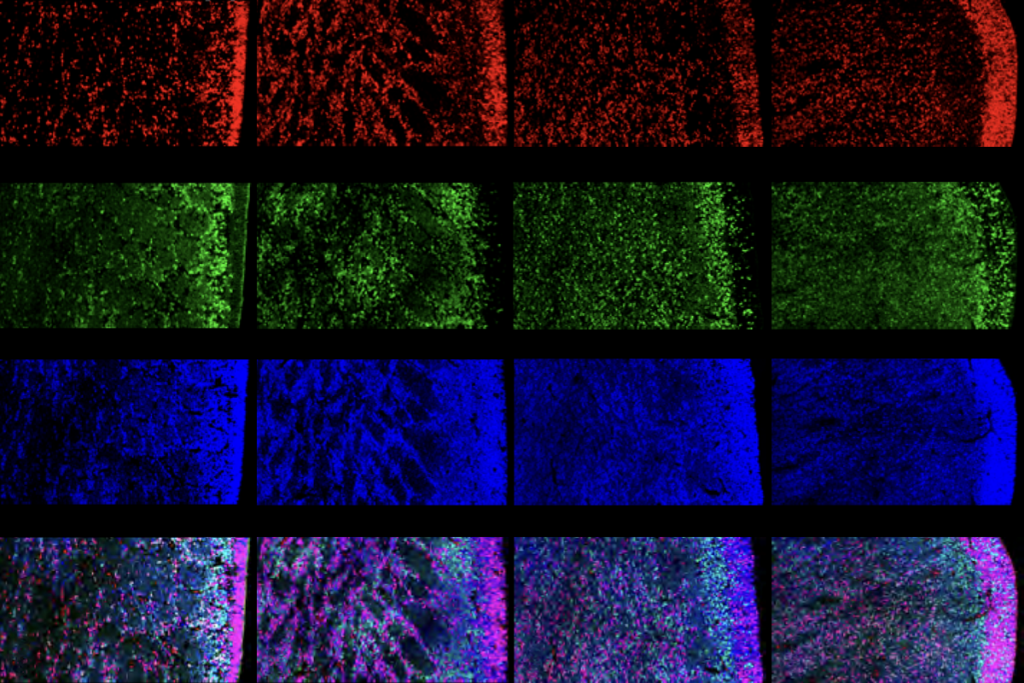

The body’s natural sleep-wake cycle may also be off-kilter. One small study found that some people with autism have mutations in the so-called ‘clock genes’ that govern the body’s circadian rhythms. And a number of studies have detected below-average levels of melatonin in this population. The hormone is secreted throughout the night by the pineal gland in the center of the brain, inducing and maintaining drowsiness.

Still, it is not clear how much any of these differences contribute to sleep problems in people with autism. While researchers try to sort this out, families are in desperate need of solutions. “Determining the cause is important,” says Robert L. Findling, vice president of psychiatric services and research at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore. “But doing something about it while the cause is being elucidated is equally important.”

That pragmatic principle also drives Malow. She started out as a sleep specialist and was drawn into the intersection of autism and insomnia by personal experience: She has two sons on the spectrum. Although her own children did not struggle with sleep, she perceived a “huge need” for solutions to this problem and started investigating it about 14 years ago. She and a few other researchers began developing techniques to teach parents how to shape a child’s schedule and home environment so as to encourage good “sleep hygiene” — life habits conducive to getting a solid night’s rest. From the get-go, Malow was interested in scalable solutions that could be made widely accessible at a low cost.

After conducting some smaller studies, Malow and several collaborators devised a sleep education program for the parents of children with autism. The program involves one or two hours of in-person instruction and two brief follow-up phone calls. It combines elements from the standard sleep-hygiene tool kit with tactics that address proclivities of people on the spectrum. From sleep hygiene came ideas such as: Set consistent times for going to bed and rising; darken the bedroom at night and brighten it upon wake-up; ensure plenty of outdoor activity by day; strictly limit caffeine and, before bed, enforce a tranquil period of winding-down time — without digital screens, whose blue light can upset circadian rhythms. From the autism field came strategies such as: Use visual cues, take advantage of a fondness for routine and sameness, and be attuned to sensory differences — no itchy sheets or pajamas and no noise from the dishwasher or other appliances at bedtime.

Malow and her colleagues tested the program with the parents of 80 children with autism, aged 2 to 10, who routinely took more than 30 minutes to fall asleep. Specially trained sleep educators at medical centers in Nashville, Denver and Toronto followed a detailed manual but were encouraged to personalize the program for each family. The results, published in 2014, showed a significant drop in the time it took the children to fall asleep after getting in bed (an interval researchers call ‘sleep latency’). Sleep latency went from an average of 58.2 minutes before the education program to 39.6 minutes afterward. To collect the sleep-related data, parents kept sleep diaries for their children, and each child wore an ‘actigraphy’ device that measured the duration of their sleep and awakenings based on their movements.

Not every child benefited, but 29 of the 80 participants, or 36 percent, were reliably falling asleep in less than half an hour on five or more nights per week after the treatment. The next step for Malow was to take the intervention out of the university and into the community.

”“There’s a lot we could be doing to tell parents how to implement some very simple and straightforward behavioral modifications.” Ruth O’Hara

Teach the parents well:

T

he Tylers learned about Malow’s newest sleep education study when they spotted a flyer in their pediatrician’s office early this year. They called and were connected with Susan Masie, an occupational therapist who oversees a group practice in Franklin, Tennessee. Masie is one of six therapists in the greater Nashville area — a mix of occupational, speech and behavioral therapists and a nurse — trained by Malow’s team to deliver the same program tested in the 2014 study. The Tylers participated in the trial, which aims to ultimately include 30 families, to see whether the approach works in a real-world setting.The Tylers completed a set of questionnaires about Jaxon’s sleep habits and their primary concerns. Then came the most exciting part for Jaxon: He got to wear the watch-like ‘actigraphy’ device to provide two weeks of baseline data on his sleep patterns. “They warned us he wasn’t going to want to take it off,” his mother says.

In May, both parents met for an hour with Masie, who walked them through an 18-slide PowerPoint presentation, stopping to chat about what was most relevant to them. Masie encouraged them to think about structuring Jaxon’s entire day so that it would culminate in restful sleep. For instance, Jaxon liked to play indoors, often in his bedroom. Masie urged them to get him outside during the day, and to move the toys out of his bedroom, which should be reserved for sleep. She also suggested more exercise. “It seems like he’s moving constantly, but he probably doesn’t get the kind of exercise he needs,” Jaxon’s father, Maurice, admitted during the session. Jaxon didn’t take naps, but he often fell asleep in the car going to and from activities. Turn on some dance music or play car games like “I Spy,” Masie offered. “Even a short nap will give him a little bit of a second wind.”

Then, together with Masie, the parents devised a simple, relaxing 30-minute bedtime routine. Masie recommended moving Jaxon’s bedtime from around 7:30 to 8 p.m. so that he would be more tired. It was possible the earlier time fell in his ‘forbidden zone’ — the period just before a person gets sleepy, when he is especially peppy and alert. Stimulating activities, such as splashing in the bathtub with his twin sister, Jordyn, or playing with his older sister, Jadyn, would have to happen before 7:30; nothing but low-key elements belonged in the bedtime routine. The schedule, hung as a colorful visual chart on Jaxon’s bedroom door, wound up like this: Quiet play→brush teeth→read→say prayers→lights out.

To keep Jaxon from bothering his parents in the wee hours of the morning, Masie introduced another visual: a sign on his parents’ bedroom door showing a sleeping moon wearing a nightcap. Jaxon was not to knock while the sign was up.

“Doable?” Masie asked. The Tylers agreed that it was. Masie reminded them to complete their “homework” of pressing a start button on the actigraphy watch at bedtime and keeping records required for the study. They agreed to meet or talk again in about a week.

Over the next few days and weeks, Jaxon and his family benefited from the new routines. The fact that school was out for the summer made it easier to move bedtimes and also to spend more time outdoors in the sun. “I was amazed what a big impact it had — not just for him, but the whole family — in regard to routine and everybody having a restful night’s sleep,” Jaxon’s mother says. At Masie’s suggestion, the Tylers began to take Jaxon to the bathroom at his new bedtime, 8 p.m., rather than waking him in the night. “That was huge,” his mother says. The actigraphy readings confirmed the improvements. Jaxon’s average bedtime moved from 7:46 p.m. to 8:28 p.m., and his wake-up time went from 5:54 a.m. to 6:55 a.m. It took him, on average, just 16 minutes to fall asleep, compared with 23 before the intervention.

Brigid Day was also recruited to the study through her pediatrician’s office. She worked directly with Lydia MacDonald, a registered nurse on Malow’s team who fills in as a sleep educator. Like the Tylers, Day was encouraged to move her son’s bedtime later and to add more outdoor activity by day and less stimulation at night. MacDonald and Day created a bedtime schedule that was customized to Nick’s preferences. He was attached to petting their beagle, Fiona, at night, so that became part of the routine: Toilet→pajamas→pet Fiona→vitamins→lights out.

The tough part for Day was breaking the co-sleeping habit. After brainstorming with MacDonald, Day decided on a variation of the so-called ‘rocking-chair method.’ She would sit on a couch in the next room while Nick tried to go to sleep. If he called, she would say, “I’m right here,” but not get up. MacDonald encouraged her to be “brief and boring” in all their exchanges after bedtime.

To manage his separation anxiety, Nick was given ‘bedtime passes,’ a strategy developed by sleep researchers in the late 1990s. These are colorful laminated cards that, as MacDonald puts it, serve as “a ticket for parent interaction.” Day says they helped Nick cope with the new routine: “He could decide when it was too much … like when it made him too sad or when he was too lonely.” If, on the other hand, he got through the night without using a pass, he would earn a reward — usually a special activity with his mother. Nick’s actigraphy numbers did not improve, but since they completed the program, Day happily reports, “we can walk upstairs, do the routine, I say goodnight, give him a kiss, we turn the light off, and I see him again in the morning.” As for Day herself: “I’m getting a whole different level of sleep,” she says.

”"It may very well be that if the child is sleeping better, [she is] going to do better in terms of learning and behavior." Beth Malow

A tiny pill:

M

alow hopes to complete the community-based trial in 2018. It’s too soon to say whether the final results will match those from the academic setting, but Malow is optimistic. Her team is already making plans to bring the approach to a wider range of families. For instance, a pilot study last year showed that the therapy also works for adolescents with autism. The study’s 18 participants took less time to nod off, on average, and spent more time in bed actually sleeping.Malow has also hatched a plan to introduce sleep education at public schools for children with autism or other conditions, such as ADHD. “Not every community has a therapy practice,” she reasons, “but every community has a school.” One elementary school near Nashville has agreed to begin offering the program early next year.

“One thing I’m really excited about is we’ll be able to take direct measures of how children are performing in class,” Malow says. “Are they staying on task? Are they attentive? Are they engaging in disruptive behavior less if they’ve had the intervention, and they are sleeping better? I think these are really important measures.”

Behavioral therapies have their limits. Malow says that, when done faithfully, these techniques can improve sleep for roughly one-third of the children who try them. There’s a sizeable group, however, who have underlying conditions that must be addressed separately. One 2016 study, for example, found that children with autism are more likely to be diagnosed with sleep-disordered breathing, including apnea, than controls are. Others may have restless leg syndrome, which presents as an irresistible urge to move the legs and therefore interferes with sleep, O’Hara says. It is difficult to assess in children on the spectrum but can be treated with dietary changes or a variety of medications.

Many children with autism and diagnosed sleep problems take drugs to help them get more rest. Although non-prescription melatonin is by far the most popular, some children are prescribed epilepsy drugs, sedatives, alpha agonists such as clonidine or antidepressants such as trazodone, depending on the nature of their problem.

A new long-acting melatonin mini-pill, just 3 millimeters in diameter, could be a game changer if its early results are borne out. Ordinary melatonin has a short half-life in the bloodstream; it may help people fall asleep but not necessarily stay asleep. The slow-release version better approximates the way the body’s own melatonin is released throughout the night. The manufacturer, Neurim Pharmaceuticals in Israel, already makes a sustained-release melatonin tablet (Circadin) approved for use by adults aged 55 and older in many European countries. But the large pill is difficult for children to swallow, and it loses its long-acting properties if crushed. In a trial of 125 children with autism or a related condition, the tiny pill yielded big results: Nearly 70 percent of the children got better sleep than before. The pill helped the children fall asleep faster, by 40 minutes compared with 13 for placebo. It also extended their total sleep time by nearly an hour — a significant improvement.

An important aspect, from a clinical perspective, is that the children were able to swallow the pill, says Paul Gringras, a lead researcher on the trial. The researchers plan to follow the children for 80 weeks and collect information on their social behavior, sleep and any possible side effects. The company hopes to make the drug available by prescription in Europe by October 2018, and will aim for U.S. approval after that.

The big hope for all of these treatments is that apart from improving sleep, they will benefit daytime behavior and learning in children on the spectrum. Anecdotally, at least, some parents say they see an improvement. Brigid Day reports that with uninterrupted sleep, Nick seems “more attentive to details.” Jaxon’s mother says she sees something similar: “I think sleeping through the night has helped with his concentration and focus at school, as well as his ability to deal with issues that would sometimes impact him emotionally.”

Jaxon is doing well in second grade, she says, and at home he’s busy creating his own pop-up books and building extravagant structures with Legos. And the entire family is sleeping better at night. “I go to bed now,” Jaxon proudly declares. His parents smile, and his father nods in agreement: “Yes, you do.”

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

Recommended reading

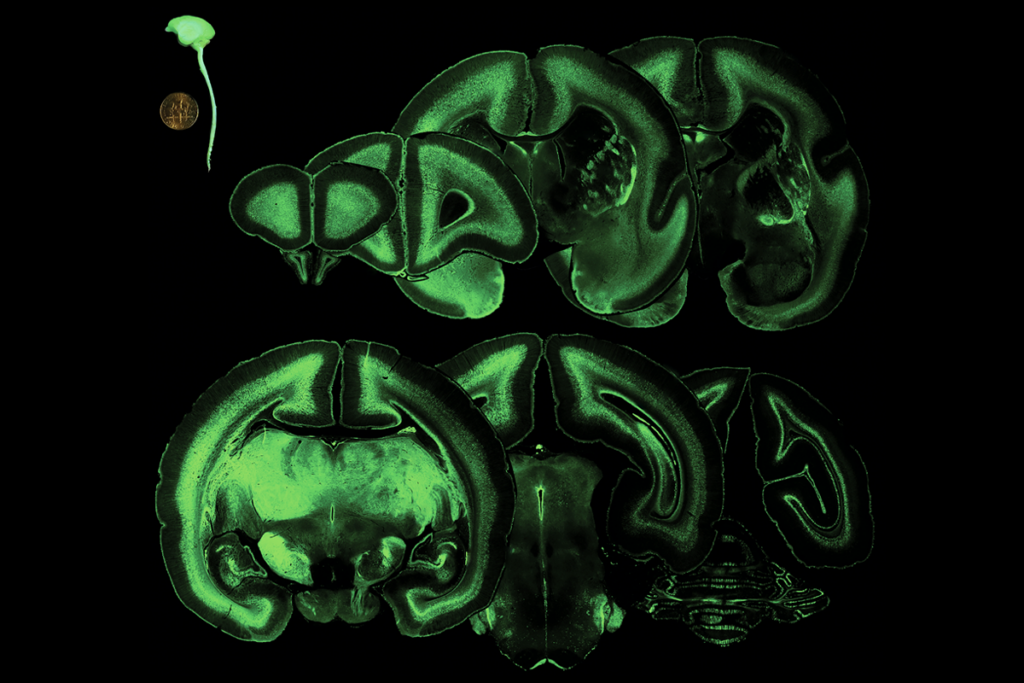

‘Tour de force’ study flags fount of interneurons in human brain

FDA website no longer warns against bogus autism therapies, and more

Prenatal viral injections prime primate brain for study

Explore more from The Transmitter

Michael Shadlen explains how theory of mind ushers nonconscious thoughts into consciousness

‘Peer review is our strength’: Q&A with Walter Koroshetz, former NINDS director