How much behavioral therapy does an autistic child need?

People tend to believe that, regardless of the treatment, more is always better. But is it?

In 1987, psychologist Ole Ivar Lovaas reported that the optimal ‘dose’ for an autism therapy he had developed was 40 hours a week. The intensive therapy, a type of applied behavior analysis (ABA), led to “normal” functioning for 9 of 19 children with autism in his study, he said1. Just 10 hours of the therapy produced small benefits. Small controlled trials of Lovaas’ therapy, however, did not fully replicate his findings on dose2,3.

The form of ABA Lovaas tested has become the most widely used autism therapy — despite controversy about its approach and findings — and 40 hours became a treatment goal for many families. ABA agencies typically market services at that intensity. And this year, that goal was formalized by the Behavior Analyst Certification Board, which recommended 30 to 40 hours of treatment per week for autistic children who need help in several areas, such as cognition, communication or social functioning. (They recommend fewer hours for children with fewer needs.)

Receiving 40 hours of weekly therapy is essentially a full-time job for a 3-year-old.

Still, people tend to believe that, regardless of the treatment, more is always better. But is it?

In an article published earlier this year, a team of researchers rightfully questions these specific requirements for autistic children4. They note, correctly, that research does not point to an optimal frequency or duration — the ‘dose,’ if you will — for ABA. In fact, a universal recommendation is unlikely to be appropriate given the heterogeneity of autism.

We need to better understand what dose is effective for which types of behavioral therapy, and for which children. Our goal should be to develop potent therapies that can be delivered within a reasonable time frame and that can be personalized for autistic children with distinct needs.

Defining success:

It is possible that all early interventions are more effective at high doses than at low ones. Or it may be that the intensive form of ABA Lovaas tested, called discrete trial training, requires more hours than other therapies do to provide benefit. We simply do not know which alternative is true, given the lack of rigorous studies comparing interventions5.

In one common study design, researchers compare a new treatment with an established therapy. But which established therapy controls get may differ among the participants. And children may get a lot of therapy or a little: Most studies do not control for dose.

If the experimental group does significantly better than controls do, it is easy to conclude that the new therapy is optimal. But if the children receiving the new therapy get more treatment than the other children do, the higher dose may have contributed to the difference — and it is impossible to tell how much.

Other studies attempt to quantify results but may conflate scheduled therapy hours with received therapy hours. Children may not receive the hours they are scheduled for due to program changes, absences, illnesses or other constraints. So these types of quantification remain crude, and none have successfully assessed the quality of the therapies.

There are ways to control for dose so that interpreting results is more straightforward.

In a 2006 study, we tested a variation on Lovaas-style ABA for children with autism. We replaced some of the ABA with content focused on joint attention or play skills for about 30 minutes per day for two of the three groups of children6. We found that this change yielded greater benefits than the ABA alone. By keeping the dose of the intervention the same for all three groups, we made sure that the interpretation would be uncomplicated.

We followed this study with one designed to gauge whether the parents could boost their children’s success by teaching them joint attention and play skills. Again we controlled the amount of contact with parents (the dose) so we could determine which of two methods was more effective: direct coaching of the parents or just parent education7. We found that direct coaching benefited children more than the parent-education method did.

Modular approach:

Given the great heterogeneity among children with autism, it is unlikely that all children require the same intervention, or even the same amount of an intervention.

Long-term studies indicate that about half of all children with autism make significant progress with early intensive interventions that require at least 20 hours per week8. Other children make slower progress, with about 30 percent remaining minimally verbal at school age despite intensive treatment9.

We might improve these numbers if we can home in on the active ingredients of a therapy, including dose, and how these factors vary by autism severity or traits9.

As we move toward greater personalization of therapy, we could apply a modular approach whereby some children receive one type of treatment (for instance, discrete trial training) for some treatment goals and another (perhaps a naturalistic, developmental method) for other goals.

Some children may need high intensity at first and then lower over time as they improve. A more economical approach would be to start all children at low intensity, assess each child’s response at a prespecified time and step up the intensity if the response is slow.

New research methodologies allow us to test these adaptive models10. Ultimately, these models may enable us to provide effective early therapy to all children who need it, including those with few resources or who live far from specialists.

Connie Kasari is professor of human development and psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

References:

- Lovaas O.I. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 55, 3-9 (1987) PubMed

- Smith T. et al. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 105, 269-285 (2000) PubMed

- Sallows G.O. and T.D. Graupner Am. J. Ment. Retard. 110, 417-438 (2005) PubMed

- Pellecchia M. et al. Autism 23, 1075-1078 (2019) PubMed

- Kasari C. and T. Smith Clin. Psychol.- Sci. Pr. 23, 260-264 (2016) Full text

- Kasari C. et al. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 47, 611-620 (2006) PubMed

- Kasari C. et al. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 83, 554-563 (2015) PubMed

- Eldevik S. et al. Am. J. Intellect. Dev. Disabil. 115, 381-405 (2010) PubMed

- Tager‐Flusberg H. and C. Kasari Autism Res. 6, 468-478 (2013) PubMed

- Almirall D. and A. Chronis-Tuscano J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 45, 383-395 (2016) PubMed

Recommended reading

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

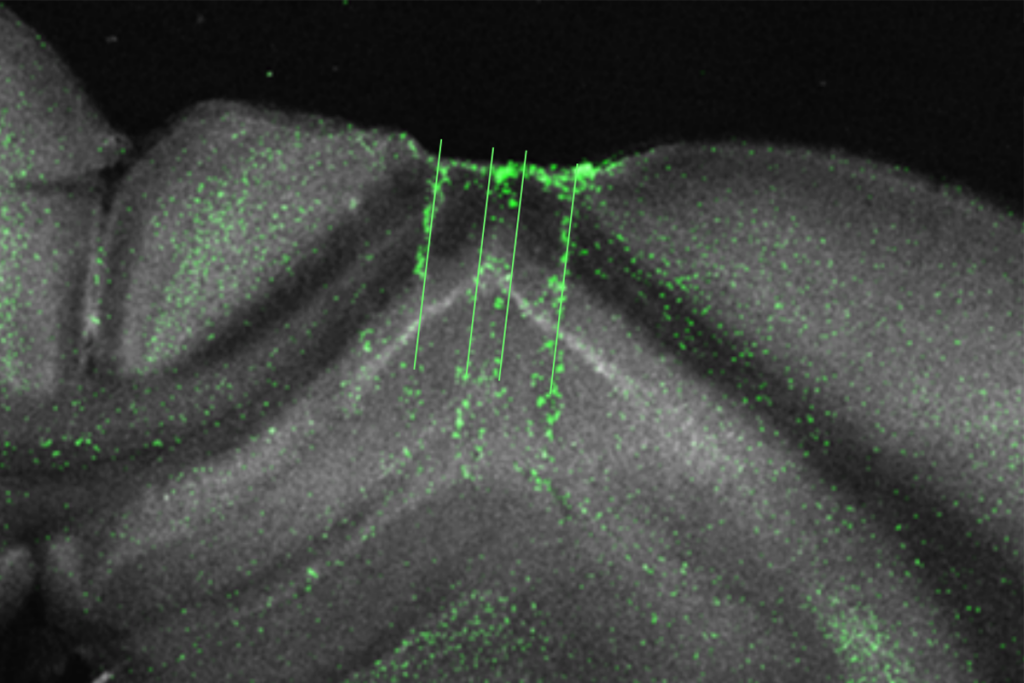

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Hippocampus builds reputation as ‘general-purpose statistical learning machine’

‘The Fox, the Shrew, and You: How Brains Evolved,’ an excerpt