Living between genders

‘Trans’ people with autism express a gender at odds with societal expectations, or reject the male-female divide entirely. Many are breaking new ground on how identity is defined — and what it means to also have autism.

Sitting by a Texas creek one afternoon, 6-year-old Ollie turned to his mother and said, “Mama, I think that I am half boy and half girl.”

Ollie’s mother, Audrey, wasn’t particularly surprised by the comment. (Audrey and the other parents in this article have requested that we use only their first names to protect their children’s privacy.) By age 2, Ollie had been drawn to “sparkly stuff and tutus.” On a shoe-shopping expedition when he was 3, Ollie had rejected his usual brown slip-on shoes in favor of pink, saying emphatically, “I need clothes in every color.” After that, Audrey says, when they went shopping she let him choose clothes in whatever colors he liked, whether they were from the ‘boys’ or ‘girls’ department. At 5, Ollie began playing ‘dress up’ at home and shortly afterward started wearing dresses in public.

“That was scary, because we were living in Texas and I didn’t know what would happen when we walked out our front door,” Audrey says.

Ollie’s parents wondered if his gender nonconformity — behavior that doesn’t match masculine and feminine norms — might have something to do with his autism. Ollie had been diagnosed with sensory processing disorder at age 2: An extreme sensitivity to sounds, light, the texture of some foods or the feel of a particular fabric can send children like Ollie into a meltdown. He also had difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep. It would take his parents four more years to find a doctor who recognized the classic symptoms of Asperger syndrome — above-average intelligence combined with social and communication deficits, and restricted interests. (Ollie was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome before the diagnosis was absorbed into the broader category of autism spectrum disorder in 2013.)

Audrey didn’t think autism was causing Ollie to like the color pink or want to wear dresses, but she did wonder whether her extremely logical child might reason that the fact that he liked those things meant he wasn’t a real boy — “like, ‘these are the rules of society,’” she says. Her husband, who serves in the U.S. military, thought that because of Ollie’s autism, the child might not understand that a boy dressing in girls’ clothes was not socially acceptable.

Ollie’s parents are not alone in pondering this puzzle. A handful of studies over the past five years — and a series of case reports going back to 1996 — show a linkage between autism and gender variance. People who feel significant distress because their gender identity differs from their birth sex — a condition known as gender dysphoria —have higher-than-expected rates of autism. Likewise, people with autism appear to have higher rates of gender dysphoria than the general population.

Between 8 and 10 percent of children and adolescents seen at gender clinics around the world meet the diagnostic criteria for autism, according to studies carried out over the past five years, while roughly 20 percent have autism traits such as impaired social and communication skills or intense focus and attention to detail. Some seek treatment for their gender dysphoria already knowing or suspecting they have autism, but the majority of people in these studies had never sought nor received an autism diagnosis. What’s more, roughly the same numbers of birth males and females appear to be affected — which is surprising, given that in the general population, autism skews male.

At this early stage of research into the overlap between autism and gender dysphoria, much remains unknown — for example, whether gender identity develops differently in people with autism. This lack of information challenges both clinicians and families who want to do what’s best for transgender children.

The combination of autism and gender dysphoria represents not just a doubling of challenges but “a multiplication of challenges,” says John Strang, a pediatric neuropsychologist at Children’s National Health System in Washington, D.C., and author of a 2014 paper exploring rates of gender dysphoria among children with autism.

Gender-dysphoric people need to clear many hurdles to live comfortably in the world. They must articulate an identity at odds with their sexual anatomy and the social expectations for that anatomy, plan and execute some form of transition, and deal with incomprehension or outright hostility as they navigate the perilous territory between genders.

“That involves a lot of transitions, flexibility, self-advocacy,” says Strang. “Those are all the weakest areas for people with autism.”

At the same time, people with autism have characteristics that can make this process easier, he says. They tend to be less worried about what other people think and less concerned about their social status or reputation.

Now 9 years old, Ollie bears out that assessment. He has endured teasing, bullying and the loss of friends and classmates; he has had to drop certain activities, such as tae kwon do, because instructors or the parents of other students are uncomfortable with his gender expression. He sees a counselor to help him deal with the way that other people sometimes treat him. “It makes me want to scream sometimes,” he says. He also has appointments each week with autism specialists to address his sensory sensitivities, fine motor skills and auditory processing.

On a late winter day, at home with his mother, his dog and his cat, Ollie is busy with Star Wars Lego, acting out a mock battle between Stormtroopers and the Rebel Alliance. He is wearing pale pink sweatpants with a glittery dark pink stripe and a pink barrette. “I’m not meant to be squeezed in that box. I’m beside it,” he says. “I’m in-between and I’m comfortable being in-between.”

Diagnostic overlap:

Over the past decade, people with gender dysphoria have developed new ways of expressing their sense of self. Whereas many once identified as transsexual or transgender, some now call themselves ‘genderqueer’ or ‘non-binary.’ Rates of autism and autism traits appear to be higher in those identifying as genderqueer. Like Ollie, these people generally say they don’t feel fully masculine or feminine, and explicitly reject the notion of two mutually exclusive genders. The word ‘trans’ is often used to encompass all of these identities and the phrase ‘affirmed gender’ to convey a person’s sense of self.

Although some trans people opt to alter their bodies via hormones or surgery, others — particularly those who identify as genderqueer or non-binary — may adopt a name and pronouns that better reflect their sense of self, without physically changing their bodies. (Ollie briefly experimented with using a feminine variant of his name and female pronouns, but it didn’t feel quite right, so he switched back.)

As with autism, the causes of gender dysphoria are poorly understood. Biological factors such as genetic predisposition, prenatal exposure to hormones, environmental toxins, and various social and psychological factors have all been proposed, but none have been confirmed. Like autism, gender dysphoria is heterogeneous, meaning that there is no one profile or presentation common to all those who identify as trans.

Only recently have researchers begun systematically exploring the overlap between gender dysphoria and autism; the first study to assess the convergence of the two conditions was published just six years ago. It included 231 children and adolescents who had been referred to the Gender Identity Clinic of the Vrije University Medical Center in Amsterdam between April 2004 and October 2007. The researchers found the incidence of autism among the children was 7.8 percent, 10 times higher than the rate in the general population. Among the adolescents in the sample, the incidence was even higher, at 9.4 percent.

Another group reported last year that more than half of 166 young people referred to the Gender Identity Development Service, a specialized British National Health Service clinic, in London between December 2011 and June 2013 had features of autism, as measured by the Social Responsiveness Scale, a screening tool for autism. Of that number, nearly half of those who scored in the severe range had not previously been assessed for autism.

Strang says he is not surprised by those results. He trained as an autism specialist, but had sampled other specialties for his internship, including at the gender clinic, and he’d seen a similar overlap there. “As soon as I started to do the evaluations, I felt like I was back in the [autism] clinic,” he says.

Inspired by the Dutch study, Strang and his colleagues approached prevalence from another angle. Instead of measuring the incidence of autism among gender-dysphoric children and adolescents, they assessed gender variance — defined as a child “wishing to be the other sex” — in children with autism. “We found rates that were 7.5 times higher than expected,” Strang says.

The researchers don’t have an explanation, but they do have a few theories. First, children with autism might be less aware of social restrictions against expressing gender variance. Second, the kind of rigid black-and-white thinking that is characteristic of autism might lead people with mild or moderate gender nonconformity to believe that they are not the sex they were assigned at birth. Third, there might be a biological connection between autism and gender dysphoria.

These are only hypotheses, as is the theory that gender identity may unfold differently in people with autism — there is little data to either support or refute them.

Rebel alliance:

Jes Grobman, 23, is a trans person with autism who is less concerned about the causes of the autism/trans overlap than about building a society that does not punish difference. Diagnosed with Asperger syndrome at 11, Grobman says many of her trans friends and acquaintances also have autism diagnoses. “I think there’s a lot of overlap between autistic people and trans people,” she says. “I am probably friends with more autistic trans people than just trans people.”

Still, it took Grobman a long time to find a community where she felt understood. Throughout much of her childhood in Chicago, she says, she felt isolated and lonely. “In middle school, I had no friends. In freshman year of high school, I spent every lunch period in the library, reading.” Middle school was particularly hellish, she says: “I was bullied and picked on.”

She began coming out of her shell at age 16, when she made friends in a Jewish youth group. But it wasn’t until she started college at American University in Washington, D.C., that she began tentatively exploring what she calls “gender feels” — admitting to herself and others that she had never really felt like a boy, without really grasping exactly what that meant. “I was able to formulate it as more of an intellectual thing,” she says. “Like, ‘what is gender, really?’”

The idea that she might be trans both intrigued and terrified her. For two years, she alternately explored and repressed her feelings. “I was very, very afraid. The narratives about trans women scared me,” she says. “I always basically understood that it would kill me, that I would be a pariah, sick and diseased, and I would lose everyone that cared about me. So I pushed it down deep inside me.”

Grobman has struggled with anxiety and depression, which are common among both transgender people and those with autism. “It’s impossible for me to separate my trans-ness and my autism from my issues with depression and anxiety,” she says. She also had conflicted feelings about her autism diagnosis: “I used to feel very, very shameful about it and tried to hide it from other people.”

It wasn’t until she began exploring her trans identity and building relationships with others in that community that Grobman was finally able to “remove all the shame and stigma and embrace the fact that I have autism,” she says. She attributes this to the confidence she developed by talking to people about being trans and being accepted for who she is without having to hide any aspect of her identity.

At first, Grobman resisted identifying as either male or female and asked her family and other people to refer to her using the gender-neutral pronouns ‘they’ and ‘them.’ Her parents were supportive up to a point, she says. But in November 2013, in the midst of an argument, her mother said, “I refuse to refer to you as ‘they.’ Realize what you are and be it.”

This was, Grobman says, “one of the most important things that anyone has ever said to me but also one of the most hurtful things anyone has ever said to me.” She decided to adopt the statement as her motto and began using feminine pronouns and taking estrogen soon afterward.

Before graduating last December, Grobman helped found a support and advocacy group called DC Trans Power. In February, she helped write a joint statement by LGBT and disability rights groups on the death early that month of Kayden Clarke, a 24-year-old trans man with autism who was shot to death by police responding to a suicide call at his home in Mesa, Arizona. Police claim that Clarke brandished a knife, and they fired in self-defense. Clarke had posted emotional videos on YouTube prior to his death, describing the challenges he faced as a person with autism seeking to begin hormone therapy. One therapist had informed him that he could not start on hormones until his autism was ‘fixed,’ Clarke said, an assertion that filled him with despair.

The statement, co-authored by Grobman and posted on the website of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network, charges that lack of adequate medical care for Clarke’s gender dysphoria precipitated a mental health crisis that led directly to his death. People with autism and other developmental disabilities and mental health issues often face resistance when seeking transition-related medical care, the activists say — a form of discrimination. “Autistic people’s gender identities are real and must be respected,” they write.

Grobman views Clarke’s death as a murder, just as she views the deaths of trans people who take their own lives due to discrimination and prejudice as murder. “The entire system is complicit in their deaths,” she says.

”“I’m in-between and I’m comfortable being in-between.” Ollie, age 9

Do no harm:

Clinicians who work with trans people who have autism say that although some individuals do encounter difficulties transitioning, healthcare providers are not always to blame. The standards of care promulgated by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health do not bar individuals with autism or other developmental disabilities from access to treatment, including hormones and surgery.

“The same criteria that applies to anybody else looking into trans medical care would apply to people on the spectrum,” says Katherine Rachlin, a clinical psychologist who has worked with adult transgender people in New York City for 25 years and is co-author of a 2014 paper on the co-occurrence of autism and gender dysphoria. “Are they informed consumers? Do they fully understand the medical procedures and treatments they are requesting? Is their experience of gender stable and enduring?”

Even people with autism who are severely affected can meet these criteria, says Rachlin, who serves on the board of directors of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health. “My experience is that even if their interpersonal deficits are severe, people are still more comfortable in their affirmed gender, no matter what else is going on in their life.”

People with autism sometimes have difficulty getting their needs met by healthcare providers due to the social and communication deficits associated with autism, says Rachlin: They may not keep their appointments, for example. “It’s not necessarily that professionals are discriminating against them on the basis of their autism,” she says.

Also, those who struggle to understand that others have beliefs, desires and perspectives that differ from their own — an impairment in ‘theory of mind’ common in people with autism — may not comprehend that others do not see them in the same way they see themselves. A person with autism may not realize, for example, that to be seen by others as a woman, they must adjust their grooming and appearance. Some of Rachlin’s clients resist taking even small steps in that direction, she says, insisting that they don’t care what other people think at the same time that they express great distress at not being correctly identified in their affirmed gender. Some also complain of deep loneliness and isolation, yet avoid social situations, refusing to attend even trans-related events and support groups.

Still, she cautions that sometimes, what looks like autism may actually be untreated gender dysphoria. “So much of the experience of being trans can look like the spectrum experience,” she says. People who don’t want to socialize in their birth genders may seem to have poor social skills, for example; they may also feel so uncomfortable with their bodies that they neglect their appearance. “That can sometimes be greatly alleviated if you give that person appropriate gender support,” she says.

Others agree with these insights. A 2015 study by researchers from Boston Children’s Hospital reported that 23.1 percent of young people presenting with gender dysphoria at a gender clinic there had possible, likely or very likely Asperger syndrome, as measured by the Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale, even though few had an existing diagnosis. Based on these findings, the researchers recommend routine autism screening at gender clinics.

But they also note that some symptoms, such as feeling different and being isolated, are associated with both conditions. Other symptoms in common include not maintaining eye contact and spending a lot of time online, according to Amy Tishelman, assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School, who worked on the study. Even the preoccupation with gender is analogous to the obsessive interests common in autism.

Tishelman says better screening and diagnostic tools, as well as specific interventions, are required for children who have both autism and gender dysphoria. “We need to develop interventions that will help them with the even more complex navigation of social circumstances,” she says.

The resistance of some parents to dual diagnoses also presents challenges. At Children’s National in Washington, D.C., some parents of children being treated for gender dysphoria were reluctant to accept that their child might also have autism, Strang says. Conversely, parents of children and teens previously diagnosed with autism wonder whether what looks like gender dysphoria may simply be an obsessive interest that will disappear in time. “Parents have expressed concerns that for some kids, gender can become a passing fixation, just like trains used to be,” Tishelman says. “There can be hesitation [about allowing their child to transition] on the part of some families because of that.”

”“So much of the experience of being trans can look like the spectrum experience.” Katherine Rachlin

Difficult choices:

Kathleen and Brad, parents of a teenager with Asperger syndrome, were flummoxed when Jazzie (Brad’s nickname for his daughter), then 14, told first her school counselor and then her mother that she was trans and that she wanted to begin hormone therapy to physically transition to the female gender. Jazzie had been diagnosed with Asperger syndrome at age 3. Her parents, particularly Kathleen, had fought a seemingly never-ending battle with public school administrators and teachers to get her the legally mandated services and accommodations she needed.

From her parents’ perspective, Jazzie’s announcement came out of the blue. They were cautious about approving irreversible medical interventions such as hormone therapy, in the event that gender proved to be a passing fixation. “[Jazzie] never said, ‘I’ve been feeling this way for years,’ or that she’d felt like this since elementary school,” says Kathleen.

But for Jazzie, it felt like her parents were “being idiots” and refusing to trust her. She spent much of her 15th and 16th years feeling resentful. “I felt like time is running out, my body is destroying itself and you are not letting me fix it,” she says now, at age 18.

Jazzie began taking hormones and using a feminine name and pronouns her last year of high school, when she was 17. “It does feel to me like if I had started sooner, I would be more me. But now, since I started so late, it’s harder to physically become as I should be,” she says. “I’m more half-formed than I should be physically.”

Brad attributes Jazzie’s assumption that her parents should have known about her gender dysphoria to Asperger syndrome. The difficulty people with autism sometimes have understanding other people’s beliefs and emotions made it hard for her to grasp that her parents could not have known about something so clearly evident to her, even though she never articulated her feelings of gender dysphoria. “She felt like we should have known,” Brad says. “But we had to tease it out of her.” Having helped a colleague transition on the job more than 20 years ago, Brad was better informed than many parents about the process, but like his wife, he felt it best to proceed cautiously.

In retrospect, Brad and Kathleen can identify a couple of incidents that might have pointed to childhood gender dysphoria — such as the time they found Jazzie, then 6, under the bed wearing pantyhose. Kathleen then found that Jazzie had stashed her old pantyhose in a desk drawer, but she assumed that Jazzie wore them because they provided the same kind of sensory comfort as the compression suit she sometimes wore at school.

Meanwhile, Jazzie insists that she has experienced gender dysphoria since early childhood. “I felt like I wasn’t a guy,” she says now. “But it wasn’t until middle school that I started feeling super distressed about it.” She has been Googling words related to gender and its variations since she was 8 or 9, she says.

Once Jazzie’s parents were sure gender wasn’t a temporary obsession, they helped smooth her transition at school by speaking with teachers, guidance counselors and administrators. They already knew how to advocate for her; their experience with autism had prepared them for this new challenge.

The parents of 5-year-old Natalie are just embarking on that journey. Referred to the autism clinic at Children’s National when she was less than 1 year old due to developmental delays, Natalie exhibited signs of gender nonconformity from a young age. When their grandmother took the family on a cruise and provided miniature captain’s suits for all the kids to wear, her brothers strutted proudly around the cabin when told how handsome they looked. Natalie, then 4, burst into tears, saying, “I don’t want to be handsome, I want to be pretty.” That year, she insisted on dressing as Queen Elsa from the Disney movie “Frozen” for Halloween.

Natalie’s father watched these developments with foreboding. “I’ve known something was up since she was 1 and a half,” he says. Natalie’s choice of toys and fantasy roles, her style of play and her mannerisms all pointed in the feminine direction, even before she was able to articulate her gender identity in words. It disturbed him, he says: “I wanted her to be a boy.” For a year, the two battled it out, but faced with a deeply unhappy and recalcitrant child, “finally, I said, ‘Okay, be a girl.’”

Since then, Natalie has been much happier, he says. He and his partner are still working out the details of Natalie’s transition to her new name and pronouns at school, and wrestling with their own feelings about the challenges ahead. Making decisions on her behalf, and supporting and advocating for her in school and in the community, is more difficult due to the lack of data on outcomes for gender non-conforming children on the autism spectrum. “Right now, we’re just taking our cues from her,” her father says. “She is still trying to find her space.”

Although science provides little help to parents of children like Natalie right now, that may soon change. Until now, all of the published studies on the co-occurrence of autism and gender dysphoria have been incidence studies, confirming that the two conditions appear together more often than expected by chance. Hoping to move the science to the next level, Strang contacted all those who have published on the phenomenon, as well as experts at gender clinics around the world. For the past two years, this group has discussed their experiences and ideas online. The result is a position paper and set of initial guidelines for diagnosis and treatment supports for people with co-occurring gender dysphoria and autism spectrum disorders. This document will lay out best practices, perhaps preventing the kind of clinical misunderstanding that drove Kayden Clarke to despair.

Strang hopes the paper will be published within the next six months. “These kids need support,” he says.

In March, North Carolina legislators passed a law barring trans people from bathrooms and locker rooms that do not match the gender on their birth certificates. For trans people with autism, who are often socially naïve and unaware of how they are perceived by others, such laws present a very real threat of the kind of confrontation they are ill-equipped to manage. Strang’s group works to help the children and teens in their program deal with such challenging situations. “We focus a lot on safety,” says Strang, “what it means to be trans in different types of communities.” Autism can create blind spots around those issues, he says, but he and his colleagues also recognize its gifts, such as intense focus and concentration.

Grobman too sees those aspects of autism as integral to her effectiveness as an activist. Her intense focus on trans and disability rights may be an obsession of sorts, she admits, but unlike her childhood preoccupation with the game Pokémon, this fixation is not trivial. Living with the threat of being bullied, assaulted or arrested for using the ‘wrong’ restroom generates near constant anxiety. Grobman says she feels driven to work for the kind of social change that will make the world a safer place for people like Ollie, Natalie, Jazzie and herself. “We need to create an understanding of the validity of trans experience and autistic experience,” Grobman says. “You are fighting for your own existence.”

Ollie seems to share that belief. Immersed in the struggle between the Rebel Alliance and the Galactic Empire on his dining room table, he keeps up a running commentary that seems an oblique reference to the challenges he faces. “They need reinforcements,” he says. “This is the last squad of troops, and they are trying to survive.”

Syndication

This article was republished in Curve.

Recommended reading

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

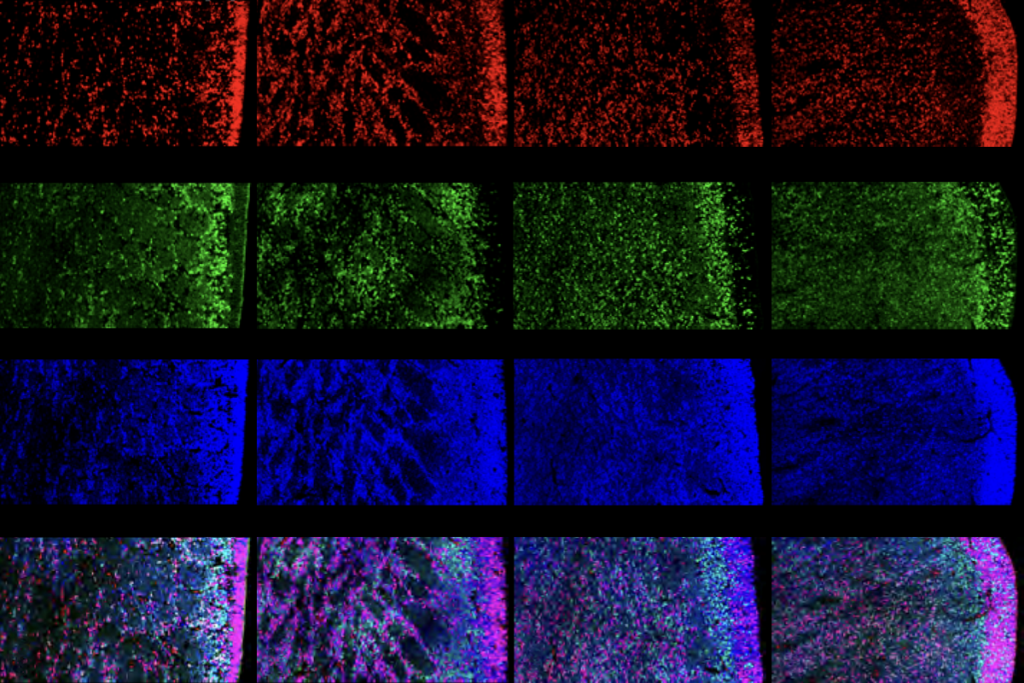

‘Tour de force’ study flags fount of interneurons in human brain

FDA website no longer warns against bogus autism therapies, and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

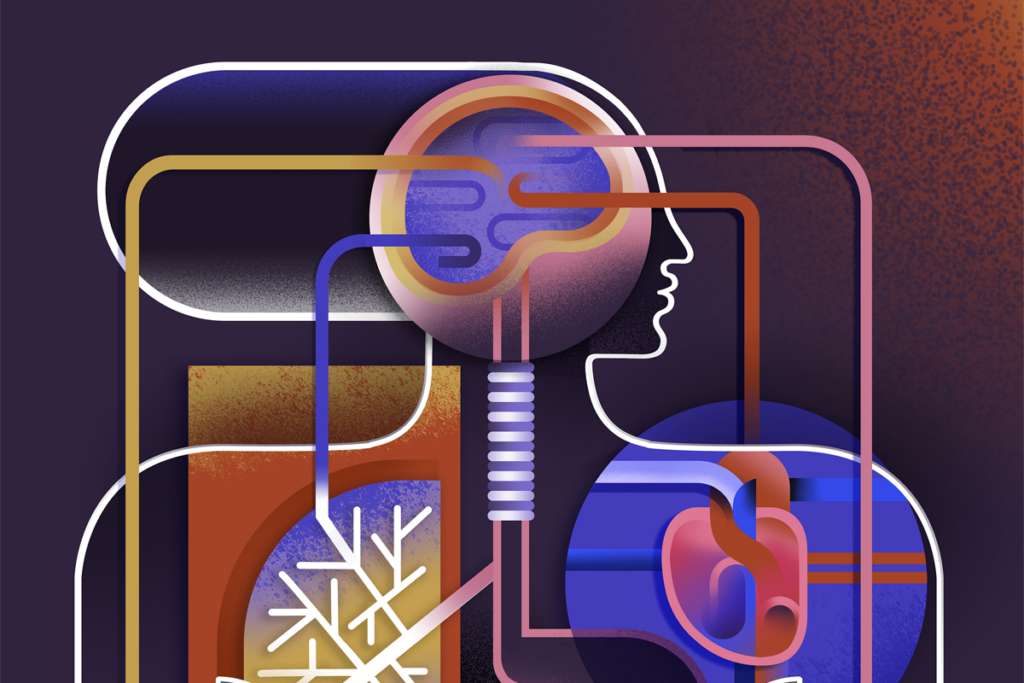

PIEZO channels are opening the study of mechanosensation in unexpected places

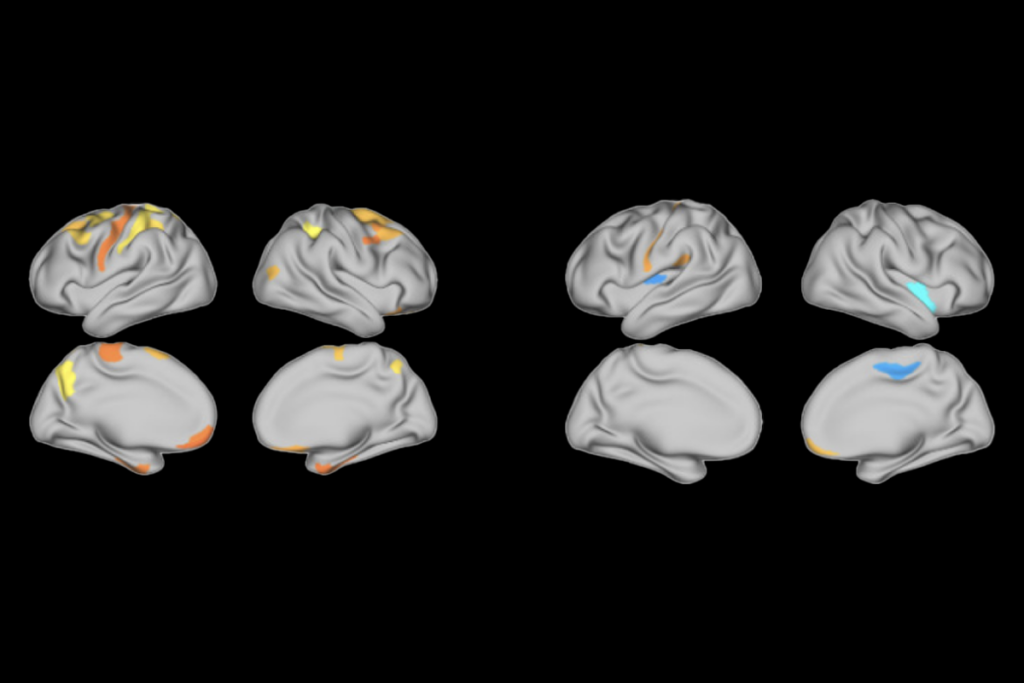

Michael Shadlen explains how theory of mind ushers nonconscious thoughts into consciousness