Lonely hunters

Cognitive traits associated with autism may have helped our ancestors survive, according to a fascinating new study. But those traits are no longer an advantage.

Ten thousand years ago, finding food and a place to sleep didn’t require social skills. In fact, obsessive tendencies, repetitive behavior and an intense focus on tools may have been a real advantage in tracking and killing animals. Similarly, a highly detailed knowledge of flora and fauna would confer a real advantage for ‘shoppers’ in the wild.

In short, traits that we consider maladaptive today — ‘disabilities’ associated with autism — may have been highly useful to our ancestors. Nature may have selected those traits to ensure survival when food supplies were limited and bands of humans were forced to disperse and forage alone, according to a fascinating new study published in Evolutionary Psychology in June.

A solitary individual foraging in the wild, for example, would know instinctively to avoid eye contact with other humans or apes likely to interpret a direct gaze as a threat. Increased levels of anxiety and super-sensitivity to sensory information would also help the solitary forager survive.

Other species provide some support for this hypothesis. For example, orangutans — genetically, the species third closest to humans — live solitary lives in the wild. Native to the islands of Borneo and Sumatra, where food is more scarce than in the African regions where gregarious chimpanzees and gorillas range, orangutans have to forage through many plants each day and travel long distances to meet their caloric requirements. Typically the animals, particularly males, meet only to mate.

Humans aren’t apes, but we do share a family resemblance in certain social behaviors and the neurological mechanisms that underlie them.

Perhaps the male bias in autism has roots in a distant past when boys marched out into the wide world alone, armed only with a spear and a genetically programmed instinct to hunt alone.

The genes responsible for these traits, which are now associated with autism, remained in the human gene pool because they were adaptive. They not only helped individuals survive, reproduce and pass on their genes, but also helped them endure long periods of solitude.

But according to this theory, these traits were probably only adaptive at what we today call a ‘subclinical’ level — similar to the broad autism phenotype — characterized by problems with language, communication and social skills not severe enough to merit a diagnosis of autism.

The autism phenotype probably developed as individuals who had similar mutations mated and produced children with more extreme and debilitating versions of the qualities they shared with their parents. That much remains true today.

The idea that traits associated with autism might be adaptive makes perfect sense. So does the observation that qualities we find dysfunctional today were not so stigmatized in less socially demanding times.

Throughout human history, certain individuals have always chosen solitary lifestyles: Think of the so-called ‘Desert Fathers’ of early Christianity, who lived alone in caves. Most, though not all, hermits were men.

In our hyper-connected age, with its emphasis on networking and communication, solitude is viewed with suspicion. But for our ancestors it may have been literally life-saving.

Recommended reading

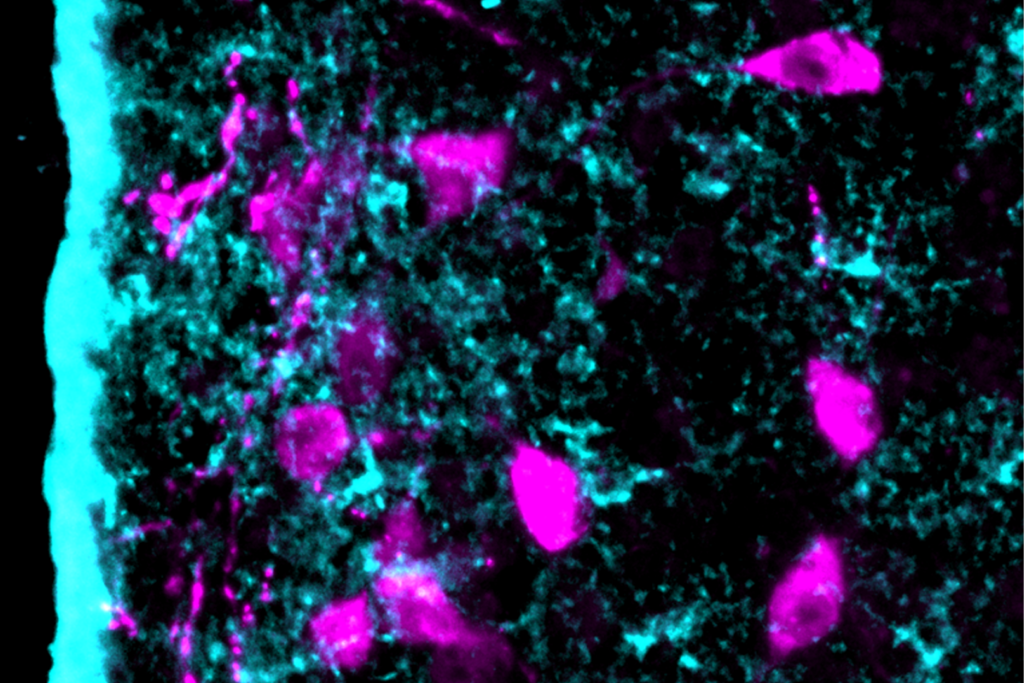

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

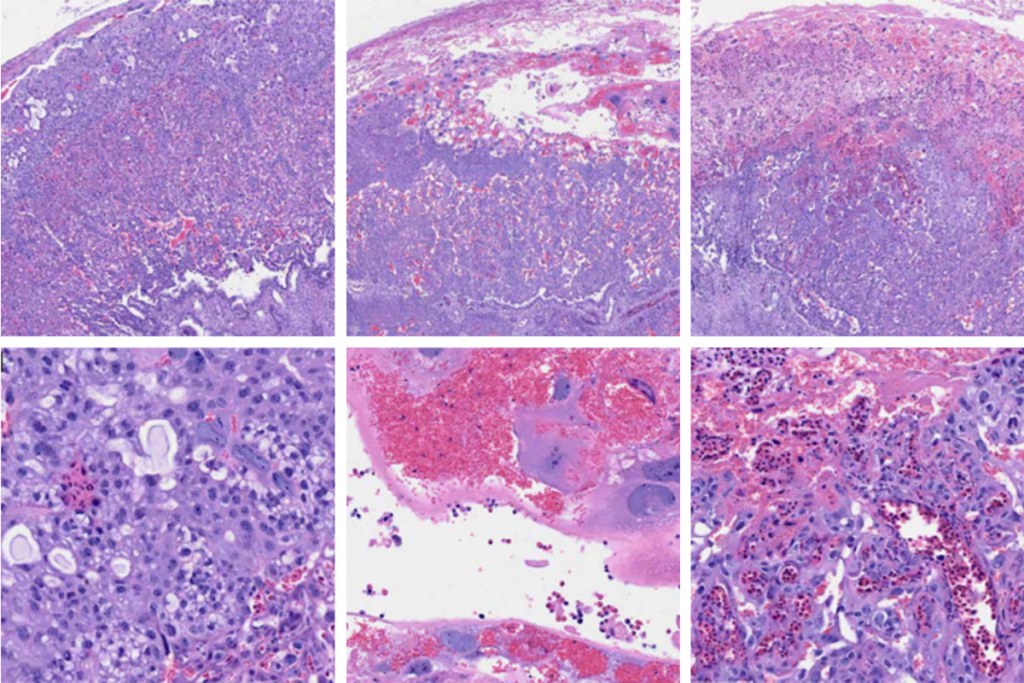

Post-infection immune conflict alters fetal development in some male mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuro’s ark: Spying on the secret sensory world of ticks

Lack of reviewers threatens robustness of neuroscience literature