Mutations in autism gene linked to distinct conditions

Individuals with mutations in an autism gene called TRIO may have a range of conditions, including intellectual disability and anomalous head size.

Individuals with mutations in a gene called TRIO may have a range of conditions, including varying degrees of intellectual disability and anomalous head size, a new study has found1. The expression of those traits depends on where in the gene the mutation lies.

The work fills the gap between clinical observations and genetic tests to show how different mutations in the gene track with distinct sets of traits.

TRIO controls the growth and migration of neurons in the brain. Previous research has linked rare TRIO mutations to autism and autism-like behaviors.

In the new study, an international team of researchers identified 24 people aged 3 to 40 who have mutations in TRIO. They sequenced the exomes — the protein-coding portions of the genome — of these people and found that many of the mutations cluster in two domains of the gene.

Clinical observations linked distinct sets of physical and cognitive traits to each domain.

“We realized that actually that particular gene caused probably two disorders, depending on where the gene fault lay,” says Diana Baralle, professor of genomic medicine at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom, who co-led the study.

One group has mutations in a domain called GEFD1. These individuals have an unusually small head — microcephaly — and generally have mild intellectual disability. Some have children and live independently or with some support from their families.

Members of the other group have mutations in the ‘seventh spectrin repeat’ domain. These people have an enlarged head, or macrocephaly, and more moderate to severe intellectual disability. The research appeared in March in the American Journal of Human Genetics.

“What is really exciting is that in this study they were able to correlate the position of the mutation in the TRIO [gene] to a clinical phenotype and even to a molecular mechanism,” says Nael Nadif Kasri, associate professor of human genetics at Radboud University in the Netherlands.

International cohort:

Baralle’s team also identified a large range of other traits, including autism, skeletal anomalies in the hands and behavioral difficulties, such as hyperactivity or aggression. These traits can be influenced by multiple genes, making it difficult to link them to specific mutations.

But because the team gathered enough participants with similar mutations, they could confirm the association between TRIO regions and intellectual disability and head size with a high degree of certainty, Kasri says.

“This was only possible because of the availability of a large cohort of patients with mutations in TRIO, combined with the identification of a molecular mechanism,” he says.

Baralle says she hopes the study raises awareness of conditions linked to TRIO and brings even more people to the clinic. For children without known conditions, identifying traits associated with TRIO mutations — such as large head size — may make it easier to be diagnosed, she says.

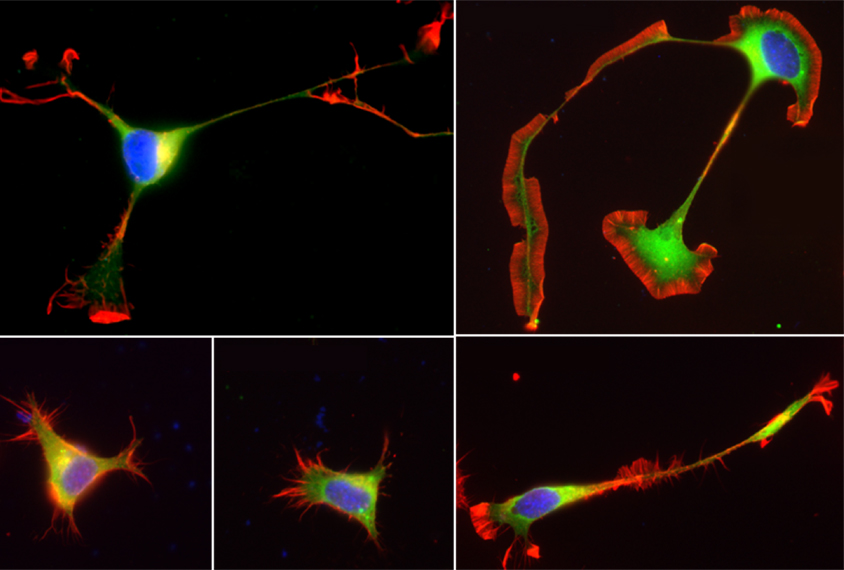

Baralle’s team also sought to identify the mutations’ effects in the brain. They introduced mutations in each of the domains into human and mouse cells.

The two sets of mutations vary in their effect on the activity of an enzyme called RAC1, the team found. The GEF domain mutations decrease RAC1 activity and blunt neurons’ growth; mutations in the spectrin domain, by contrast, boost RAC1 activity and neuronal growth.

The team then used the CRISPR gene-editing tool to replicate the two sets of mutations in western clawed frogs. As in people, mutations in the GEF domain resulted in frogs with small head size and those in the spectrin domain in frogs with large head size.

“That’s a very sort of quick and dirty way of showing the same as we were seeing in the humans,” Baralle says.

Her team next plans to delete just one copy of each TRIO domain in the frogs instead of both copies — which would better represent the situation in people.

References:

- Barbosa S. et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 106, 338-355 (2020) PubMed

Recommended reading

INSAR takes ‘intentional break’ from annual summer webinar series

Dosage of X or Y chromosome relates to distinct outcomes; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Xiao-Jing Wang outlines the future of theoretical neuroscience

Memory study sparks debate over statistical methods