A reanalysis of data published in a 2024 Nature paper spotlights the tension between curiosity and caution when searching for gene candidates.

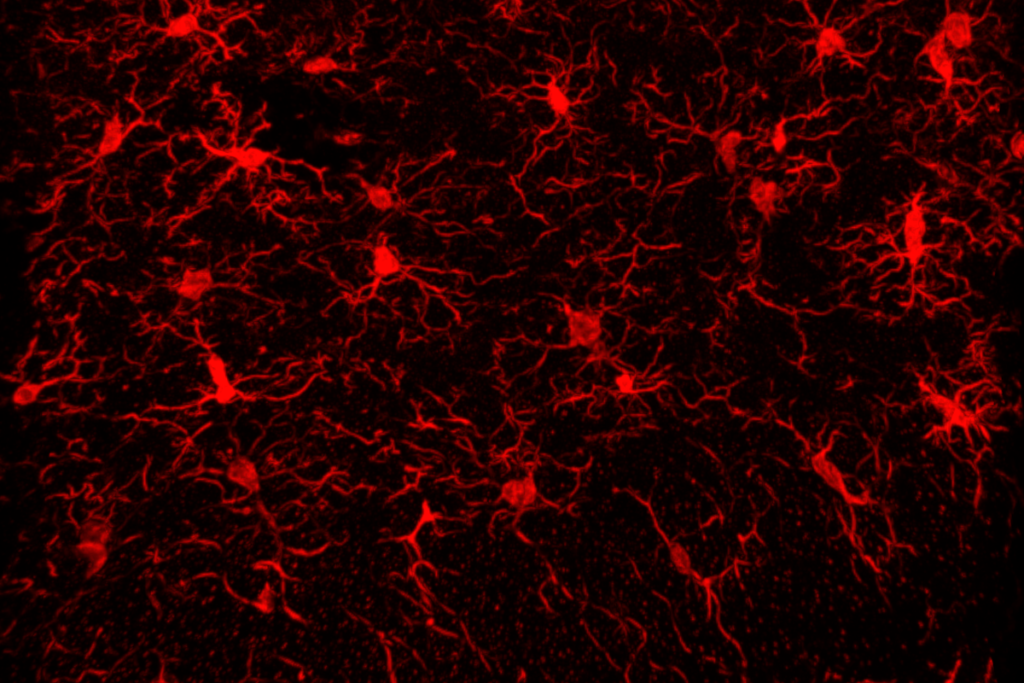

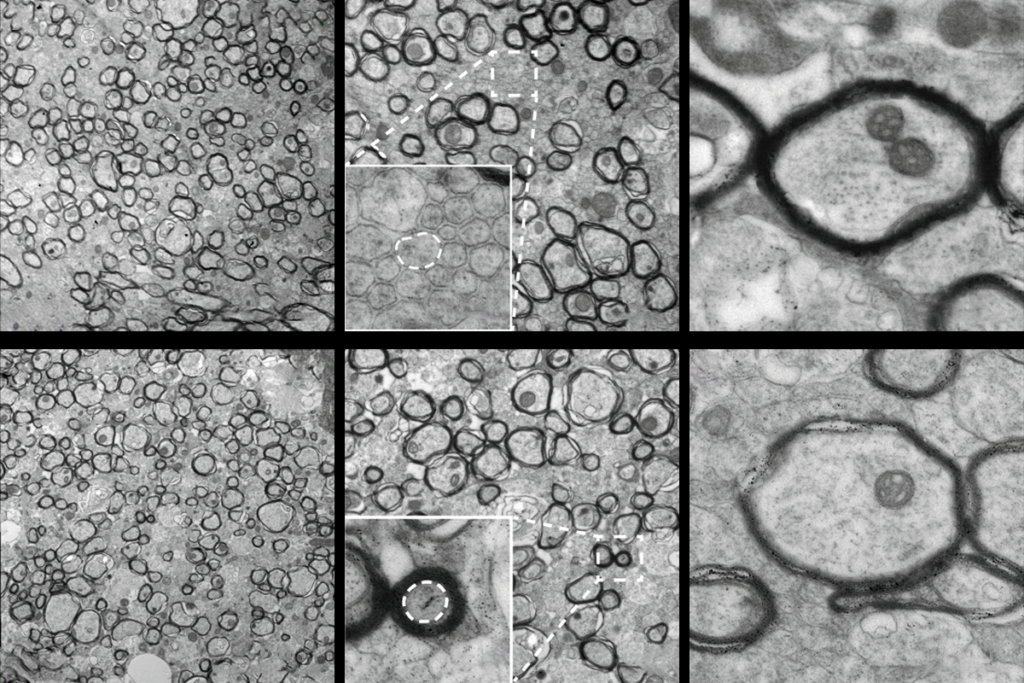

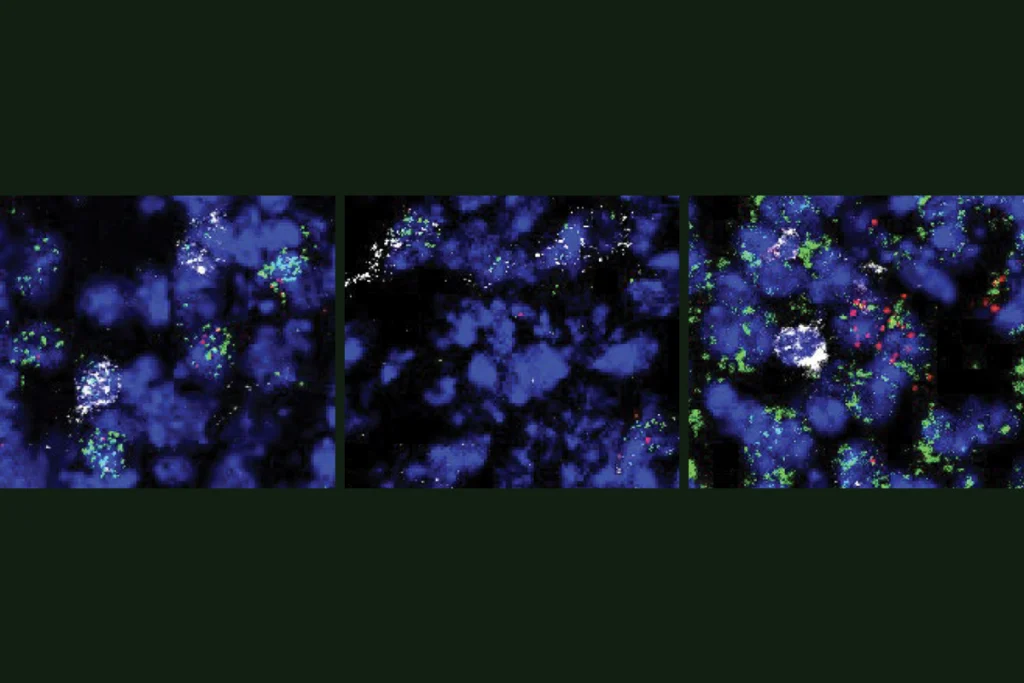

The 2024 study, led by Stephen Quake, professor of bioengineering and applied physics at Stanford University, claimed to reveal changes in gene expression associated with a mouse’s memory of a foot shock. Quake and his colleagues used single-cell RNA sequencing to identify 107 genes that were differentially expressed across six types of neurons in part of the brain’s fear center, the basolateral amygdala.

But the team behind the reanalysis says the study authors failed to address the risk of false-positive findings. In a response to the study published 4 June in Nature’s Matters Arising section, Eran Mukamel, associate professor of cognitive science at University of California, San Diego; and Zhaoxia Yu, professor of statistics at University of California, Irvine, wrote that it’s standard practice in large-scale genomic studies to apply a statistical correction known as the Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate method.

Quake and his colleagues tested the expression of 3,350 genes in response to a fear memory. Without the Benjamini-Hochberg correction, a p-value of 0.05 would be expected to yield about 160 false positives, Mukamel and Yu wrote (about 5 percent of the genes would appear to be statistically relevant by pure chance). When the pair reanalyzed the study data with the Benjamini-Hochberg correction, none of the 107 genes highlighted in the study passed the threshold for statistical significance.

In a reply to Mukamel and Yu, Quake and his co-senior author, Thomas Südhof, professor of molecular and cellular physiology at Stanford and winner of the 2013 Nobel Prize, defended their decision to forego the Benjamini-Hochberg correction to avoid “overlooking genuine effects by making the criteria for significance overly stringent.” But similar studies by the authors, including a Nature paper published just after the fear memory study, applied the correction.

“Either Südhof and Quake do not accept that ‘a more relaxed approach is appropriate’ or they haven’t read the Methods sections of their own papers,” Lior Pachter, professor of computational biology and computing and mathematical sciences at the California Institute of Technology, wrote in a 16 June blog post.

Nature defended the journal’s decision to publish the study without the Benjamini-Hochberg correction. “We select reviewers to ensure that all technical aspects of each study are properly assessed. This includes the use of any statistical tests, and we ask reviewers specifically to provide comment on their appropriateness,” a spokesperson told The Transmitter. “We welcome scientific debate and discussion about papers published in the journal—they are a vital part of the scientific process. The publication of the Matters Arising and Reply from the authors of the original paper underscores our commitment to fostering scientific discourse.”

Mukamel, Pachter, Quake, Südhof and Yu did not respond to The Transmitter’s multiple requests for comment. The Transmitter has previously covered errors in or retractions of other papers led by Südhof.

M

ukamel and Yu criticized the study’s treatment of single cells from one mouse as independent samples, too. “Differences among individuals are a critical source of variability in biological data. By treating single cells as independent samples, the statistical analysis ignores the within-sample dependence and leads to overconfident results,” they wrote.The best way to account for this, the pair wrote, is to apply a “pseudobulking” approach that pools together cells of a given type from each animal. When they applied such an approach to the study data, batching data from individual cells into bulk samples from the same mice, only 21 genes met the threshold for significance. After the Benjamini-Hochberg correction, none of the genes retained their significance.

The authors also engaged in a form of statistical “double-dipping,” according to Mukamel, Yu and Pachter. By restricting their analysis to genes with “biologically meaningful regulation,” they stacked their sample with genes they assumed would show changes in expression “even if no true differences were present,” Mukamel and Yu wrote.

“By neglecting best practices such as adjustment for multiple comparisons and accounting for dependence across cells from the same animal, research based on RNA sequencing risks an accumulation of irreproducible findings,” they wrote.

The critique highlights a “thorny problem” in genetics research, says Timothy O’Leary, professor of information engineering and neuroscience at the University of Cambridge, who was not involved with the original study or the reanalysis.

“It wouldn’t be fair to dismiss all the results based on an unconservative statistical analyses,” O’Leary says. “On the other hand, it would also not be reasonable to say, ‘Let’s trust the statistical analysis at face value and believe all of these genes are somehow implicated in fear memory.’ That would be reckless, and I don’t think a mature, experienced scientist who would read this paper would do that.”

Taking a conservative approach “doesn’t guarantee good science,” O’Leary adds. “It can lead to missed opportunities, missed inferences and, in fact, wasted time and resources as well.”

Quake and his colleagues followed up on select leads from their RNA-sequencing approach with in-situ hybridization experiments, which illuminate RNA expression in slices of brain tissue. This approach provided additional evidence that certain genes are involved in fear memory, though whether the results are reproducible remains to be seen, O’Leary says.

“A research paper is a research paper. It is not a concrete statement of fact. It is a work in progress,” O’Leary says. “There’s a big discussion to be had about how telegraphic and how clear we should be about limitations of research. In my view, we should be far clearer than we are. We leave a lot of those things implicit.”