AI-assisted coding: 10 simple rules to maintain scientific rigor

These guidelines can help researchers ensure the integrity of their work while accelerating progress on important scientific questions.

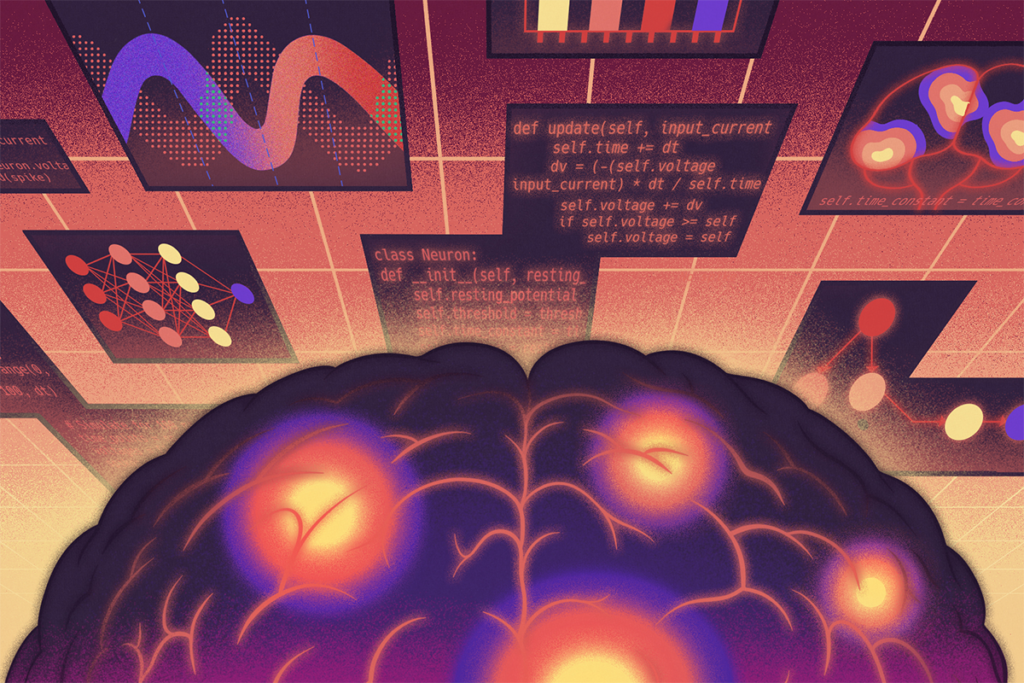

For better or worse, nearly every neuroscientist is now an amateur software engineer to some degree. Some of us write simple data-analysis scripts; others write complex software packages implementing entire workflows for data acquisition, analysis or simulation. Because the accuracy and reproducibility of our science critically depends on whether our software operates correctly, I started digging deeply into the software engineering literature over the past decade; I wanted to figure out what insights might be brought to bear on scientific software engineering to help reduce the likelihood of errors that affect scientific conclusions.

For several years, I led workshops for our students on how to generate reproducible code, using what I had learned from the software engineering literature. Then, in 2022, everything started to change. With the advent of GitHub’s Copilot, followed by the release of GPT-4 in early 2023, it became clear that large language models had the potential to generate code that met or exceeded the quality of that generated by humans. In the three years since then, the power of AI-assisted coding tools has exploded, with one analysis estimating that the ability of LLMs to solve difficult coding problems is increasing at a super-exponential rate, doubling its performance every seven months. In the past year, agentic coding tools, which allow an LLM to employ external tools and operate autonomously, have further pushed the limits of what artificial intelligence can do.

Given this power, nearly every scientist is now using LLMs to assist with coding in some way, either through the use of chatbots, such as ChatGPT or Claude; the use of integrated coding agents in tools, such as Visual Studio Code or Cursor; or the use of coding agents, such as those available via Claude Code or Cursor. In theory, this has the potential to accelerate scientific work, and the code generated by LLMs is often of better quality than that created by the average amateur programmer. However, there are also many reasons for concern.

Foremost, these assistants can make it too easy for researchers to generate code that they don’t understand. This is problematic both because it can make debugging difficult and because it means that the researcher is relying on critical infrastructure that has not necessarily been subjected to the kind of rigorous testing and quality assurance that we often expect of scientific code. AI coding assistants change the user from a generator of code to a reader and reviewer of code, but they don’t change the fact that the user needs to understand what the code is doing and ultimately take responsibility for it as a scientific product.

Inspired by the rapidly growing prevalence of AI-assisted coding tools and our experiences with those tools, in an October preprint my colleagues and I laid out 10 simple rules for using AI coding assistants in scientific work. Here, I provide a broad overview of these rules along four main themes and what they mean for neuroscientists; I encourage you to read the preprint for more details, along with my open-access living textbook, which delves deeply into best practices for the use of AI coding assistants for science.

F

I saw the sharp end of this recently when I tried to use Claude Code to generate a Python implementation of a popular neuroimaging analysis tool—the “randomise” tool from the FSL software package—that would take advantage of the Mac GPU to speed up operation on my Mac. I am not a GPU expert, so I simply let Claude Code go, and in a short amount of time I had a working app. However, some quick testing showed that despite Claude’s claims, the GPU was not actually being used, and the code was substantially slower than the original FSL code. I spent several hours working with Claude to try to debug this, only to have it finally realize that the algorithm that I had provided for it wouldn’t actually work on the Mac GPU. This provided me with a blunt lesson about the dangers of coding beyond one’s knowledge base using AI coding assistants.

Second, it’s critically important to understand how to effectively work with AI coding assistants. This means that one needs to specify the problem as clearly as possible to the assistant before it starts writing code. Workflows for effective prompting of coding agents are still emerging, but in general, the user starts with a “project requirements document” that outlines the project specifications in detail, and then uses LLMs to help generate a task list to guide the work of the assistant.

It’s also important to carefully manage the context of the model, which refers to the information currently active in the model’s working memory. The goal of context management is to make sure that the model has all of the information that it needs, and as little extraneous information as possible, within its current context. Though the context windows of language models continue to grow in size, there is increasing evidence that information tends to get lost in large context windows (a phenomenon known as “context rot”), so context management remains critically important.

Third, testing is essential to validate the code generated by an AI assistant. We recommend the use of a “test-driven development” approach, in which the researcher develops an initial set of tests that together assess whether each of the intended features of the code are working properly. AI tools can be useful in helping to write tests, but they must be used with caution; assistants can often generate tests that don’t adequately assess the problem of interest, or they may change tests simply in order to pass.

Finally, we highlight the scientist’s continued responsibility to ensure that all code generated by the project is valid. To quote our preprint, “‘AI wrote it’ is not a valid defense for flawed methodology or incorrect results.” Though “vibe coding,” referring to the generation of code by AI assistants with little human oversight, may be useful and often successful for building websites, it’s almost certainly a recipe for disaster when it comes to scientific programming.

AI coding tools will undoubtedly continue to become more powerful and will play an increasingly important role in the computational work of scientists. By following the guidelines laid out in our preprint, researchers can maintain the integrity of their work while accelerating progress on important scientific questions.

Recommended reading

How neuroscientists are using AI

Lack of reviewers threatens robustness of neuroscience literature

Explore more from The Transmitter

Should neuroscientists ‘vibe code’?

How neuroscientists are using AI