In early life, astrocytes help to mold neural pathways in response to the environment. In adulthood, however, those cells curb plasticity by secreting a protein that stabilizes circuits, according to a mouse study published last month in Nature.

“It’s a new and unique take on the field,” says Ciaran Murphy-Royal, assistant professor of neuroscience at Montreal University, who was not involved in the study. Most research focuses on how glial cells drive plasticity but “not how they apply the brakes,” he says.

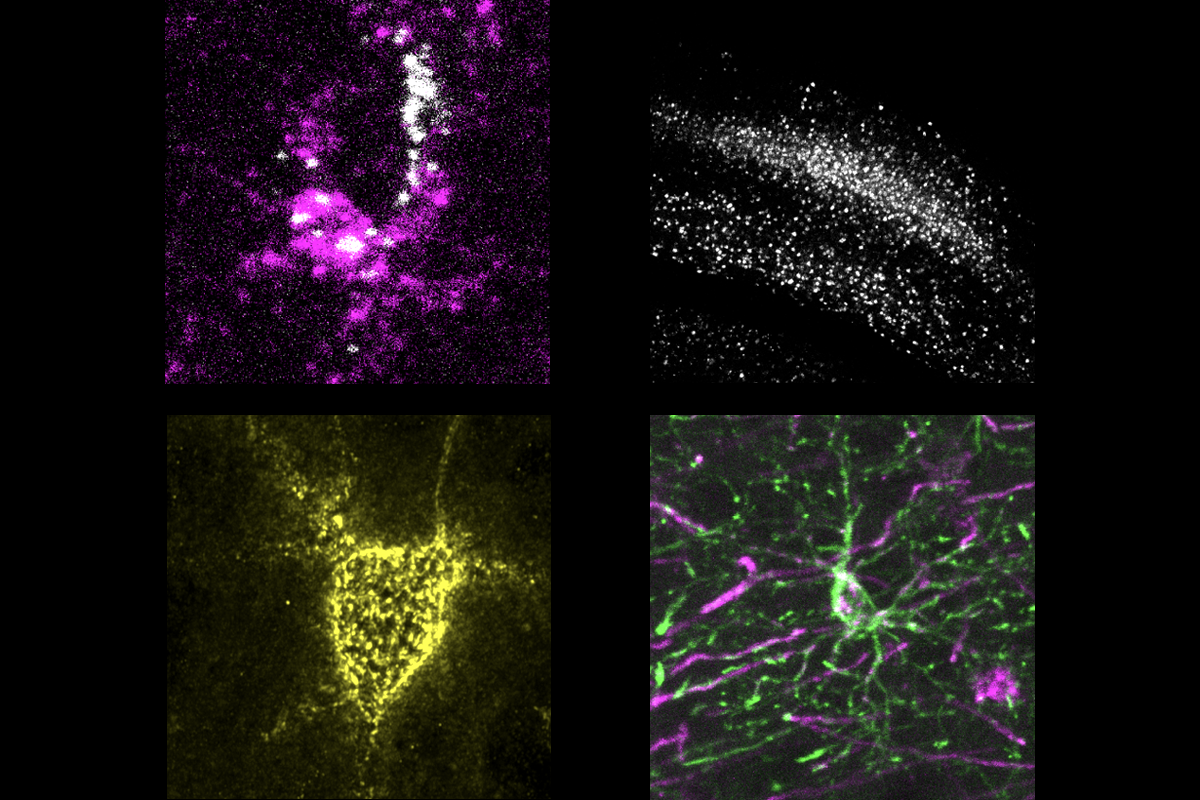

Astrocytes promote synaptic remodeling during the development of sensory circuits by secreting factors and exerting physical control—in humans, a single astrocyte can clamp onto 2 million synapses, previous studies suggest. But the glial cells are also responsible for shutting down critical periods for vision and motor circuits in mice and fruit flies, respectively.

It has been unclear whether this loss of plasticity can be reversed. Some evidence hints that modifying the neuronal environment—through matrix degradation or transplantation of young neurons—can rekindle flexibility in adult brains.

The new findings confirm that in adulthood, plasticity is only dormant, rather than lost entirely, says Nicola Allen, professor of molecular neurobiology at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and an investigator on the new paper. “Neurons don’t lose an intrinsic ability to remodel, but that process is controlled by secreted factors in the environment,” she says.

Specifically, astrocytes orchestrate that dormancy by releasing CCN1, a protein that stabilizes circuits by prompting the maturation of inhibitory neurons and glial cells, Allen’s team found. The findings suggest that astrocytes have an active role in stabilizing adult brain circuits.

The loss of plasticity in adulthood is often seen as a “sad feature of getting older,” says Laura Sancho Fernandez, project manager in Guoping Feng’s lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who worked on the study as a postdoctoral researcher in Allen’s lab. “But it’s really important for maintaining stable representations and circuits in the brain.”

S

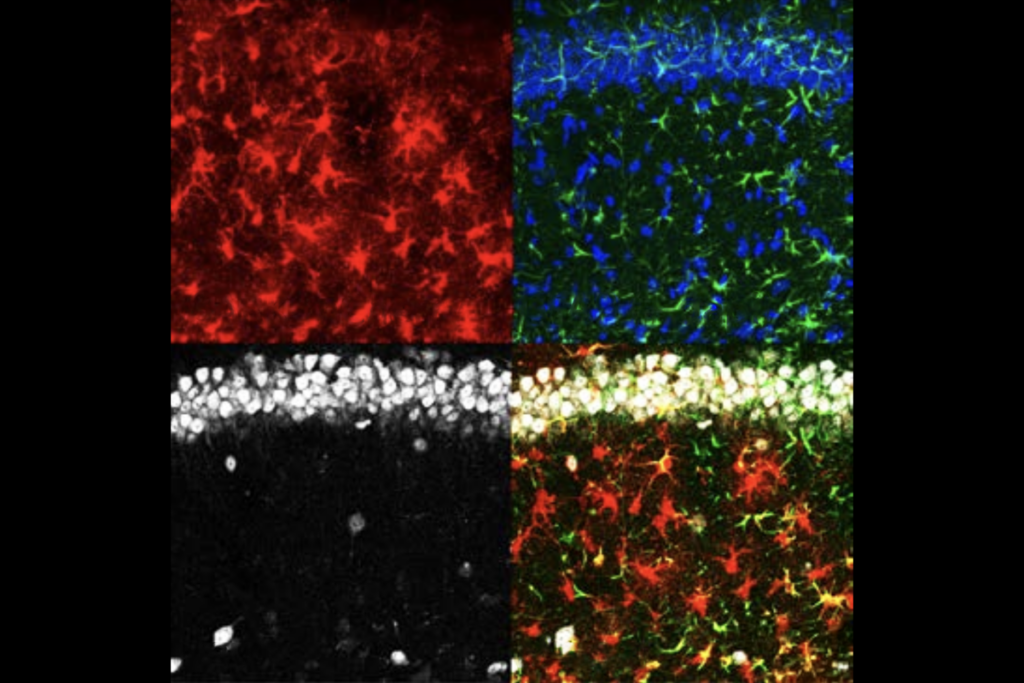

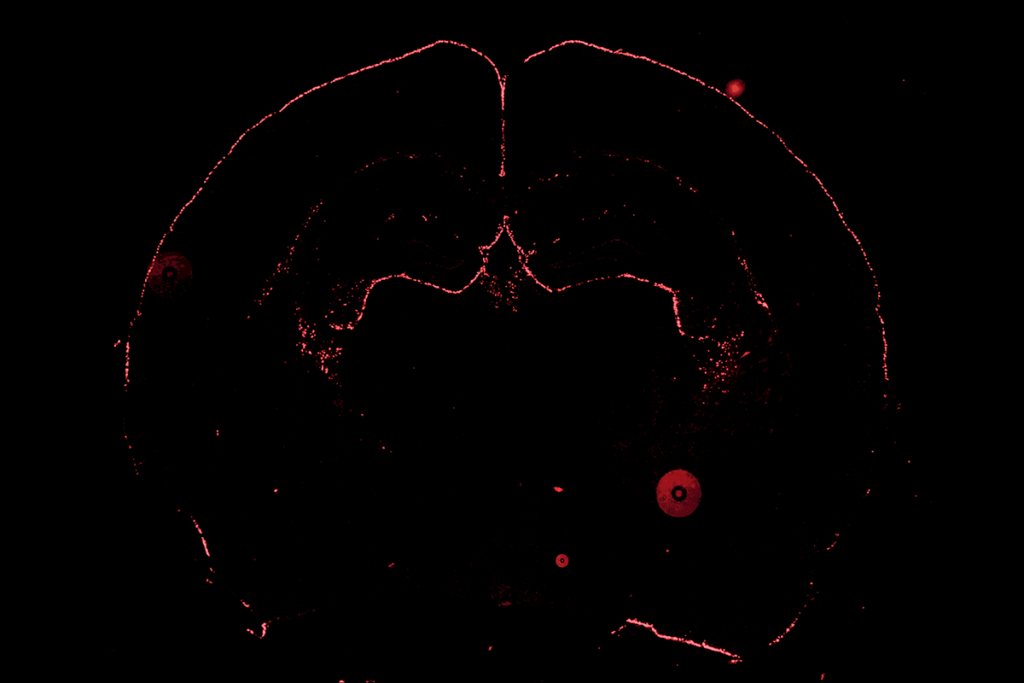

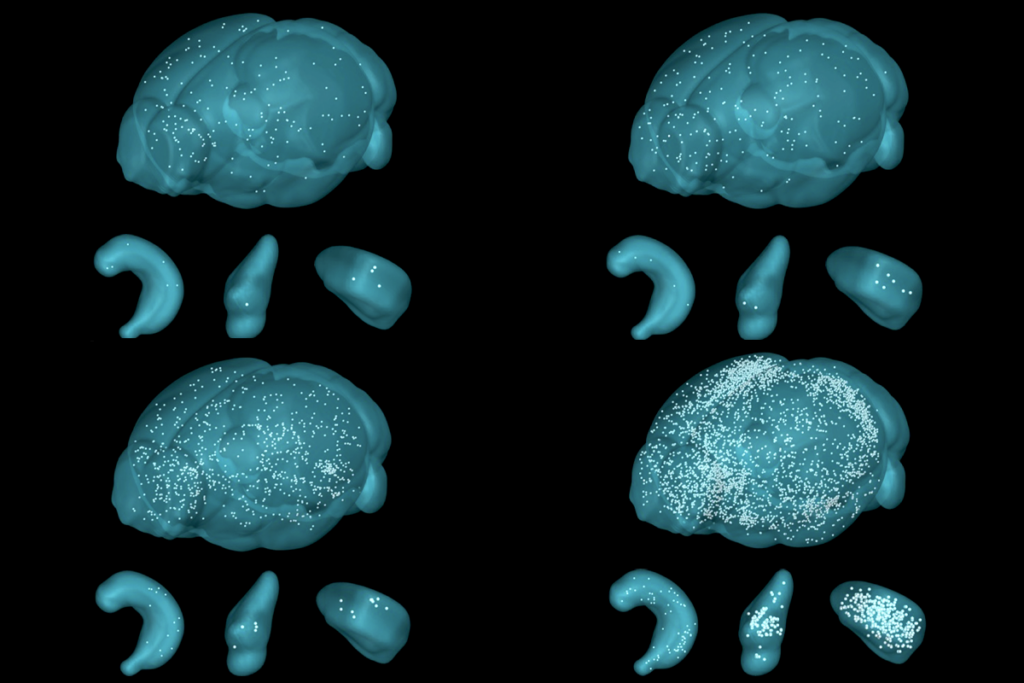

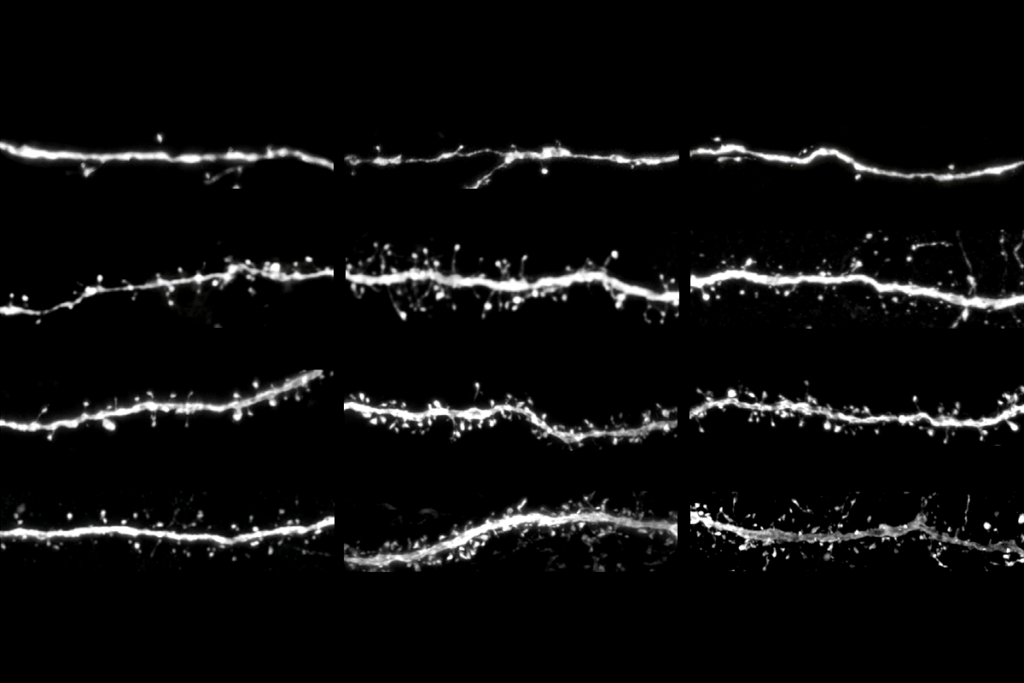

ancho Fernandez and her colleagues happened on CCN1 when they analyzed astrocytic genes that activate after brain development. The gene is dormant in 4-week-old juvenile mice—a critical period for visual plasticity—but surges in adulthood, the analysis found.Neural circuits in the visual cortex stabilize prematurely in juvenile mice engineered to express CCN1 in astrocytes, the study found. Likewise, suppressing the gene’s typical rise in adult mice promotes plasticity in the region and destabilizes established brain circuits. These mice possess fewer neurons specialized for binocular vision and show problems in depth perception—a skill that relies on integrating visual information from both eyes—compared with wildtype animals.

CCN1 may lock in neural pathways by prompting the maturation of multiple cell types. Mice that overexpress CCN1 have a higher density of perineuronal nets, cage-like structures that surround inhibitory neurons. The emergence of these nets coincides with the end of the critical period. And inhibitory cells in those mice receive more excitatory input than in wildtype mice, suggesting that CCN1 promotes their maturation.

The mice also have elevated numbers of mature oligodendrocytes and highly branched (or ramified) microglia, the study found.

All those cell types “are a lot for one molecule to coordinate,” says Marc Freeman, director of the Vollum Institute at Oregon Health & Science University, who was not involved in the study. Whether CCN1 directly interacts with multiple cells or mediates those changes through another molecule is “an interesting question,” he says.

The findings suggest that astrocytes could be leveraged to tune plasticity after development, says Michael Wheeler, assistant professor of neurology at Harvard University, who did not take part in the new work. “If you can adjust CCN1-dependent plasticity, then you can start to understand how circuits reorganize in other contexts, like injury or disease.”

In fact, CCN1 appears to be pivotal to recovery following spinal cord injury. Astrocytes churn out the protein in response to damage, signaling to microglia to sweep up cellular debris, according to an independent team’s paper that was published alongside the new study.

W

hether CCN1 also stabilizes circuits in other cortical regions, however, is unclear. Data in the new study show that the gene’s expression varies throughout the brain, which suggests that different proteins—released by astrocytes or additional cell types—may take over elsewhere.“Looking at other brain regions will be important,” Allen says. Her lab is particularly interested in probing the hippocampus, she says, a brain structure known to retain a degree of flexibility throughout life. That, and identifying the pathways upstream of CCN1, are her group’s next goals, she says.

What ultimately drives circuit stabilization is a big open question, Murphy-Royal says. “There’s no big clock that gets you from birth to adulthood. So what’s the endogenous cue that tells the brain it’s no longer a child?” he asks. “We really haven’t got a clue.”