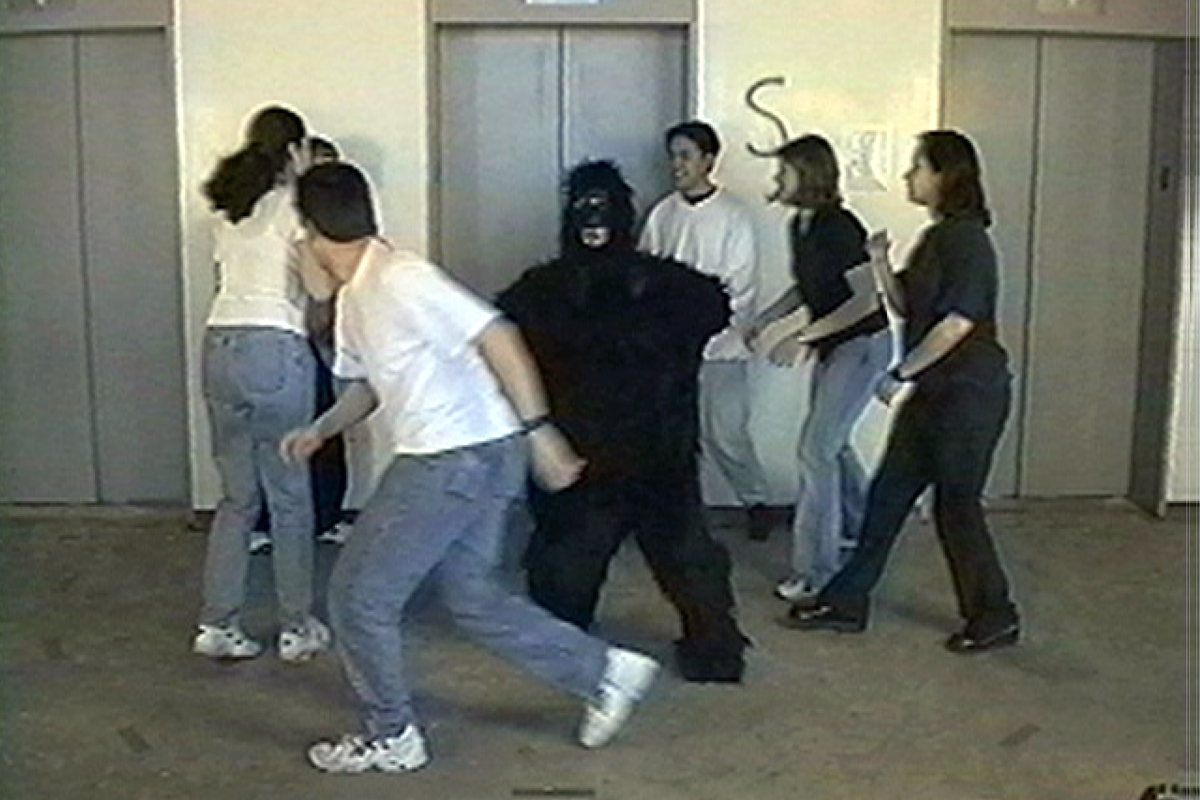

The famous “invisible gorilla” experiment has captivated the psychology community since it was published in 1999. About half of the participants—who had to count the number of basketball passes in a video—failed to notice a 5-second cameo in which a person in a gorilla suit danced her way among the players. Some scientists interpreted that failure, called inattentional blindness, as evidence that visual awareness requires attention.

But attention is not essential after all, a new study suggests. People can accurately describe some details in a scene even if they focused their attention elsewhere and reported not noticing them, the study shows.

Inattentional blindness “is a side effect of something that we do really, really well … we have to be able to focus our attention on things we care about and not be distracted,” says Daniel Simons, professor of psychology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and co-investigator of the gorilla experiment. Simons was not involved in the new study. But awareness is not all-or-nothing, as the new study demonstrates, he adds.

The results, published last month in eLife, challenge some scholars’ interpretation of inattentional blindness, says Ian Phillips, the study’s principal investigator and professor of philosophy and psychological and brain sciences at Johns Hopkins University. Several theories of consciousness, such as the global neuronal workspace, attended intermediate representation, and attention schema theories, “have seized on this kind of data as showing that attention is the crucial ingredient. It’s kind of the gate or the magic that needs to turn information coming in through the eyes into conscious experience,” Phillips says. He believes those views are incorrect, he says.

Most studies of inattentional blindness, including the gorilla experiment, ask participants a yes-or-no question about whether they noticed something unusual in a visual prompt. “These questions are famously problematic,” Phillips says. Researchers typically assume that a “no” means someone did not see or retain traces of information about the unexpected stimulus, he says. But what counts as unusual? And how sure does someone need to be before they would respond yes? Phillips asks. These uncertainties could lead the participants to report not noticing a stimulus when they did, he says.

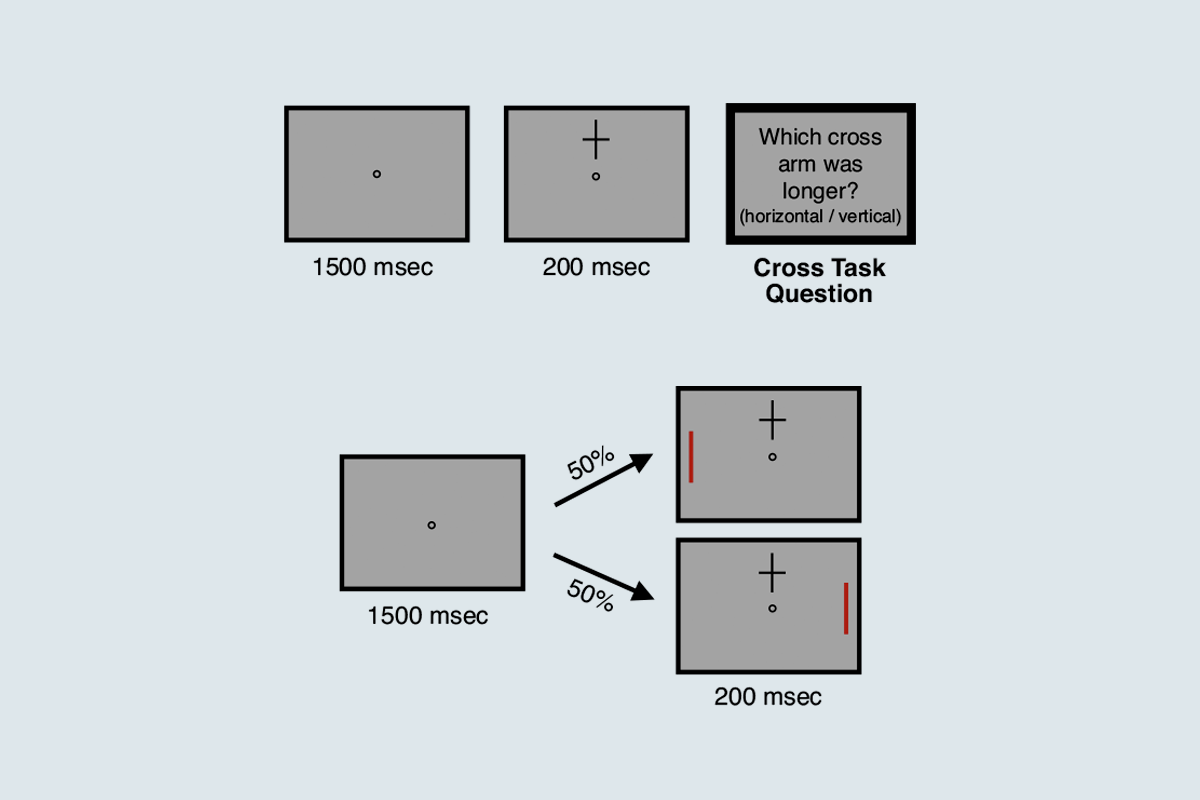

So Phillips and his team came up with ways to quantify biases in participants’ responses and gauge their visual sensitivities. More than 25,000 people participated in one of the team’s five-part online experiments, which required participants to focus their attention on simple shapes, such as moving black or white squares, or a cross with varying arm lengths in the center of a screen.