Beyond the algorithmic oracle: Rethinking machine learning in behavioral neuroscience

Machine learning should not be a replacement for human judgment but rather help us embrace the various assumptions and interpretations that shape behavioral research.

Machine learning has enabled researchers to extract meaningful patterns from datasets of unprecedented scale and complexity, revolutionizing fields from protein-folding prediction to astronomical object classification. Just as microscopes opened spatial scales inaccessible to the naked eye, machine-learning tools can reveal patterns at data scales that exceed human cognitive capacity, transforming vast collections of measurements into interpretable scientific insights.

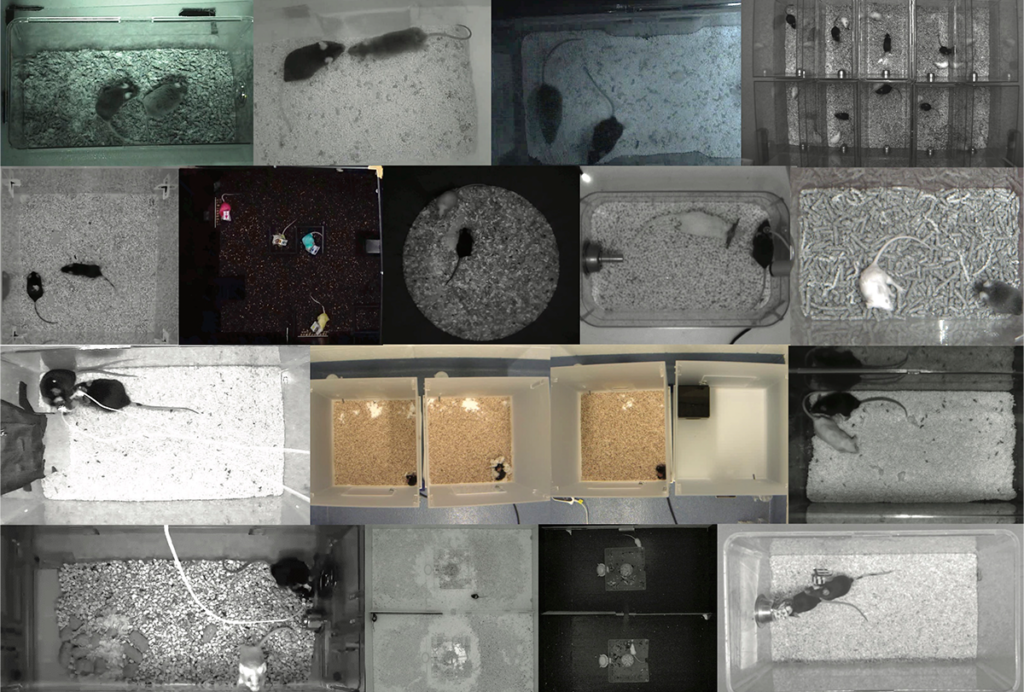

In behavioral neuroscience, new automated techniques have made it possible to study animals in an extraordinary level of detail. By sifting through terabytes of video and audio data, these methods can extract simple patterns that are time consuming for human observers to annotate, as well as surface patterns and correlations that are too subtle or complex for human eyes to catch. Their findings are already shifting long-standing dogmas around behavior, such as how and when information is integrated for decision-making. Importantly, these techniques are also expanding the ability to study naturalistic behavior, enabling researchers to capture the complexity of real-world behavior without sacrificing the control and precision that traditional lab studies afford.

Unsupervised methods appear especially promising because of their potential to help the field address two enduring challenges: moving from restrictive experiments that have traditionally yielded easily measurable—yet simple—movements to those that more fully capture the repertoire of natural animal behaviors; and, second, defining and organizing the basic units of behavior without importing the categories and intuitions of the human observer. In other words, scientists are increasingly optimistic that the machine can carve nature at its joints.

However, it is important to remember that algorithms can subtly encode the very human assumptions that unsupervised methods are supposedly designed to bypass, influencing not just which patterns they detect but what ultimately counts as “behavior” in the first place. How can researchers define behaviors—especially when they are complex or occur during novel tasks or in unfamiliar species—in a way that respects both the precision demands of computational analysis and human interpretability? We believe the answer lies in treating machine-learning tools as interpretive instruments whose outputs reflect the assumption of their designers rather than ground truth.

I

n practice, behavioral quantification using machine learning usually begins with pose estimation, which automatically extracts the position of an animal’s body parts from video frames, followed by action segmentation, which divides continuous animal poses into discrete behavioral units such as grooming, rearing or exploring. This computational pipeline promises to reproducibly scale analysis far beyond the limits of manual annotation, revealing temporal structure and behavioral variability that would be invisible to a researcher watching videos.Action segmentation, typically via supervised classification or unsupervised clustering, appears to be a straightforward technical procedure. However, it is a crucial site of scientific judgment where philosophical assumptions about the nature of behavior become embedded in code. Deciding which features to extract from pose data, how temporal boundaries between behaviors should be defined, and what constitutes meaningful behavioral structure all reflect particular theories about animal behavior. These modeling choices determine not only which patterns the algorithm can detect but also what aspects of behavior remain systematically invisible to its analysis.

The scientific consequences of these design choices become apparent when researchers deploy behavioral analysis tools in practice, often without a clear sense of which method will perform best for their specific data. As they compare different approaches, they may notice that some methods struggle with particular aspects of their data, whereas others perform well. These differences are commonly attributed to technical factors, such as insufficient training data, incorrect hyperparameters or lack of previous validation on a particular model organism. But these differences in performance may actually stem from mismatches between algorithmic assumptions and researchers’ assumptions about the behaviors they are measuring.

Rather than viewing the challenge of parsing behavior as a problem to be solved solely through better algorithms, we might instead recognize it as revealing something essential about the nature of behavioral research itself. Experimentalists with hundreds of hours of experience observing their animals develop pattern recognition that differs fundamentally from researchers working with large, multispecies datasets processed through standardized pipelines. What an algorithm might flag as noise or error could represent, to an experienced observer, an intriguing individual variation that opens new avenues for investigation.

Resolving these differences may require embracing the human observer in the analytical process, rather than removing them from it. Careful video review remains crucial for understanding not just what behaviors are being detected but how and when segmentation decisions are made. Watching algorithms parse behavioral sequences teaches us far more about the nuances of movement and the assumptions embedded in computational models than statistical summaries alone can do.

The real power of machine learning may lie not in greater objectivity, as is often claimed, but in making explicit the assumptions and interpretations that have always shaped behavioral research. Behavioral analysis tools, for example, do not simply reveal preexisting structures; they help reshape what behavior means as a scientific category, opening new ways of seeing animal movement and generating novel empirical questions to explore.

S

cientists make choices at every stage of behavioral experimentation, including when designing tasks, selecting recording instruments, developing analysis algorithms, interpreting results, and so on. For example, researchers may represent behavior in their machine-learning algorithms as continuous or discrete, or decide when variation across trials reveals adaptive and flexible behavior versus when it reflects genuine error. Thus, the active role of the experimenter—even in algorithm design—challenges the belief that machine-learning techniques provide theory-free insight into complex systems, as interpretation plays a crucial role in both behavioral quantification and its understanding.This limitation isn’t insurmountable, however. We view it as an opportunity to develop a more sophisticated understanding of how to incorporate machine learning into scientific practice. As Liam Paninski and John Cunningham argue in their 2018 review, these techniques must exist within an experiment-analysis-theory loop, in which data analysis not only extracts meaningful information from experimental data but also generates hypotheses, suggests new experiments and helps to refine theories. As researchers refine each step of this loop, they need to explicitly consider the assumptions embedded in both their experiments and the algorithms they use. Such an approach transforms machine learning from a replacement for human judgment into an instrument for reflection—one that both surfaces human assumptions and explicitly encodes them in algorithm design to reveal new dimensions of behavior.

This perspective transforms potential limitations into scientific assets. Behavioral research is by its nature interdisciplinary, but various perspectives and conceptual frameworks about behavior may not naturally standardize and cohere. Instead of eliminating their variability, however, we can leverage these differences to develop more robust and nuanced understandings of behavior. Recognizing the interpretive nature of behavioral analysis will not impede scientific progress but instead make it more meaningful by ensuring that sophisticated analytical capabilities serve genuine scientific understanding rather than replace it.

AI use disclosure

Recommended reading

‘Bird Brains and Behavior,’ an excerpt

Nonsense correlations and how to avoid them

On fashion in neuroscience: In defense of freezing behavior

Explore more from The Transmitter

Should neuroscientists ‘vibe code’?

Competition seeks new algorithms to classify social behavior in animals