How artificial agents can help us understand social recognition

Neuroscience is chasing the complexity of social behavior, yet we have not answered the simplest question in the chain: How does a brain know “who is who”? Emerging multi-agent artificial intelligence may help accelerate our understanding of this fundamental computation.

Who are you?

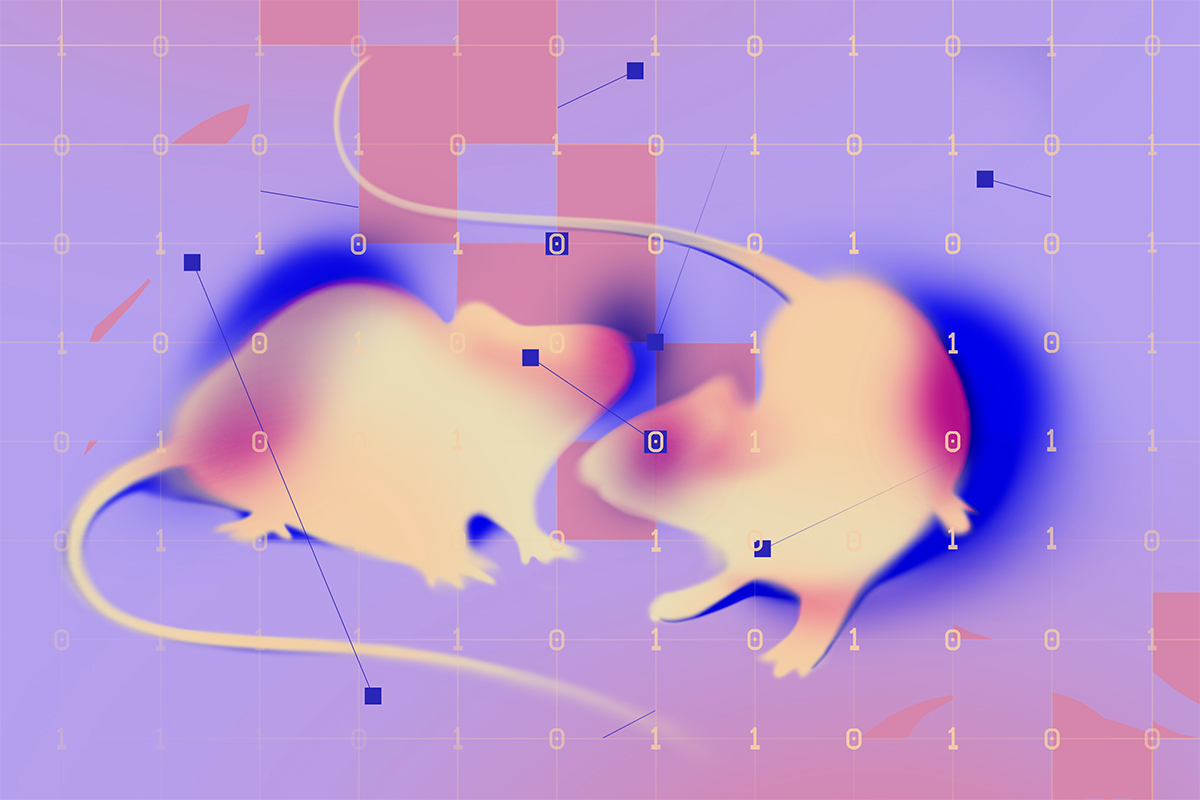

It sounds trivial, but this question sits at the heart of every social encounter. When we meet a stranger at a party or catch a glimpse of a familiar colleague across the room, our brain must rapidly determine who this person is, retrieve the relevant memories and update expectations about how the interaction will unfold. Animals face the same challenge: In natural social groups, survival depends on rapidly distinguishing individuals—beyond simple familiarity detection—and recalling relevant information, such as dominance rank or past interactions, within seconds. Across species, social recognition is the first computation that enables all subsequent social behavior.

Yet, even as the field dives into increasingly complex social behaviors—communication, cooperation, competition—we still lack a mechanistic understanding of this most fundamental step in building successful social relationships: How does a brain know who another individual is? Where is identity encoded, and what neural machinery allows recognition to be so fast and accurate?

Across the brain, multiple regions contribute to social memory, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex and hypothalamus. When it comes to computing individual-specific information, the hippocampus has emerged as a key hub. Recent work demonstrates that the hippocampus performs specialized neural computations for individual recognition across its subregions. Yet how identity information flows from the synapse level to the broader circuit level remains unknown.

Combining experimental neuroscience with multi-agent artificial-intelligence systems, such as large language models, offers a promising strategy for elucidating the neural architecture of social recognition, potentially revealing principles inaccessible via either approach alone.

LLMs support compositional reasoning, long-range associative integration and in-context learning—properties that make them well suited for exploring how identity representations emerge, update and generalize across many interacting partners. These traits transform LLMs from passive text predictors into platforms for studying individual-specific social computations in the brain.

LLMs also display coordinated, social-like behaviors, making it possible to study these kinds of interactions at a larger scale. In a study published last year in Science, researchers showed that multi-agent recurrent neural networks can learn cooperative strategies that mirror animal behavior—an exciting demonstration that artificial agents can acquire socially relevant computations.

LLMs extend this approach by enabling much richer long-range associative structure and flexible context-dependent inference, while avoiding the temporal bottlenecks and limited memory capacity of recurrent architectures. This allows a larger number of agents to interact, influence one another and maintain structured social models at scale.

S

First, we need to break down synaptic mechanisms that support identity coding. Synaptic plasticity is widely considered the substrate of learning and memory, yet we still do not know which types or timescales of plasticity enable the neural computations involved in distinguishing individuals. A new in-vivo synaptic imaging tool developed by the Allen Institute now allows hundreds of synapses to be monitored during behavior. Applying these approaches to social-memory hubs such as hippocampal subregions could reveal the “synaptic fingerprint” of identity representations. Multi-agent recurrent neural network models can accelerate this effort. When equipped with biologically inspired plasticity rules, these networks allow us to observe how identity representations emerge across layers, track weight updates as agents interact, and manipulate experience histories in ways impossible to do in animal experiments. Such models can generate candidate synaptic rules for rapid identity recognition, offering hypotheses that biological experiments can directly test.

A second question is the capacity of social intelligence: How many distinct individuals can a brain accurately distinguish? By comparison, studies in spatial coding have revealed discrete details about the brain’s processing, such as how many place fields single hippocampal neurons can form. We know much less about the capacity and sparsity of social identity coding. Addressing this will require behavioral paradigms in which animals interact with many social partners, combined with advances in simultaneous multi-animal recording techniques—for example, miniaturized two-photon imaging and wireless electrophysiology that enable neural activity to be monitored from several interacting animals at once. This is where multi-agent LLMs can shine. The machine-learning field has already begun to scale up interacting agents, including recent demonstrations of human-like social dynamics emerging among five LLM-based agents. These systems offer the flexibility to increase the number of agents far beyond what is feasible in animal experiments. By examining how internal embeddings evolve as agents encounter and differentiate one another, we can infer potential social capacity limits and representational strategies that biological circuits might use.

Finally, animal behavior is often shaped by task design, making it hard to study the mechanisms underlying social recognition that occurs spontaneously in naturalistic settings. Multi-agent LLMs, by contrast, allow us to observe which identity-sensitive computations arise without explicit reinforcement, offering insight into the intrinsic structure of social recognition. These emergent patterns can point to computations the brain might perform even in the absence of external instruction.

Social recognition happens within seconds but shapes social behavior across a lifetime. When this computation breaks down—as in autism and related neurodevelopmental conditions—the consequences cascade across social learning and interaction. Clarifying how identity is encoded—from synapses to population-level computations and even across interacting brains—is essential for understanding more complex social dynamics. Achieving this will require much tighter collaboration between experimental neuroscientists and AI researchers, working together to identify where identity representations fail and how they might be restored.

Recommended reading

Seeing the world as animals do: How to leverage generative AI for ecological neuroscience

Explore more from The Transmitter