Oligodendrocytes need mechanical cues to myelinate axons correctly

Without the mechanosensor TMEM63A, the cells cannot deposit the appropriate amount of insulation, according to a new study.

Oligodendrocytes are master sculptors: They wrap central nervous system axons in cloaks of insulating myelin that have a thickness and length tailored to each axon’s diameter. Yet it was unclear how these glia arrive at such precise proportions.

Schwann cells, which myelinate peripheral nerves, respond to the levels of the growth factor neuregulin 1 type III on an axon to apply the appropriate amount of insulation. Oligodendrocytes, however, operate without neuroregulin and can myelinate synthetic nanofibers, which do not give biochemical cues. Oligodendrocytes also have a more complex job than Schwann cells. Each Schwann cell produces one sheath of myelin on one part of a single axon; a single oligodendrocyte wraps up to 60 axon segments of varying diameter.

“All this decision-making has to come by [a] single cell,” so relying on biochemical cues is “not the way to go,” says Amit Agarwal, a group leader at Heidelberg University.

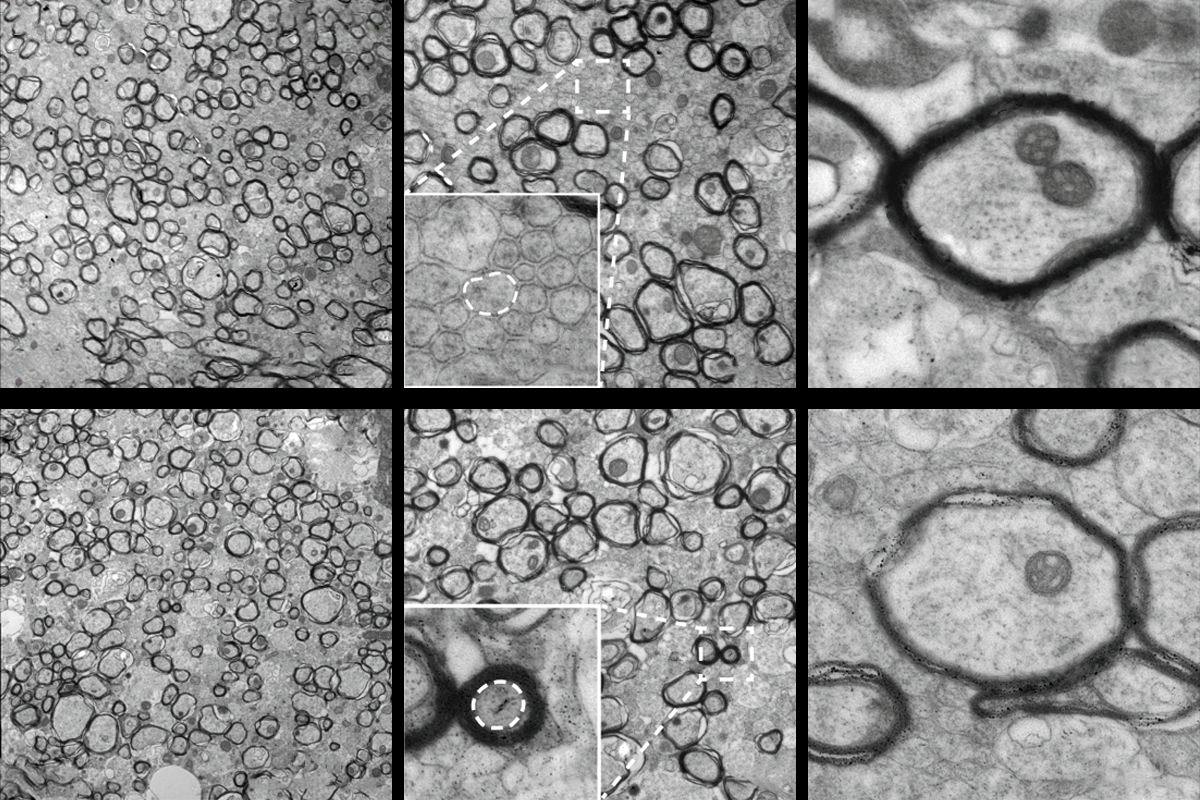

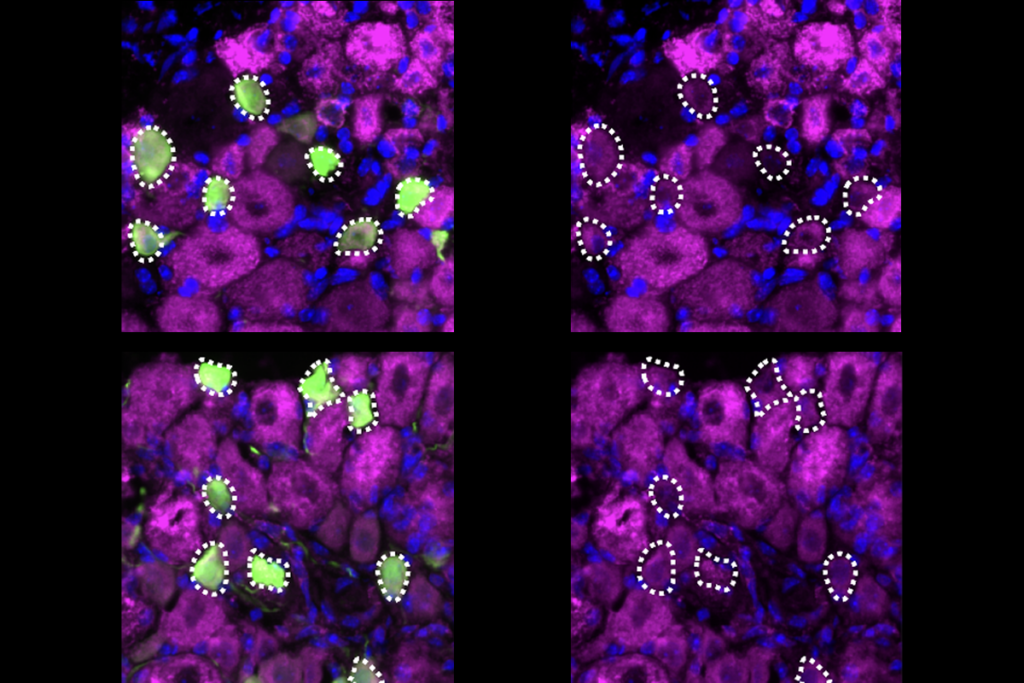

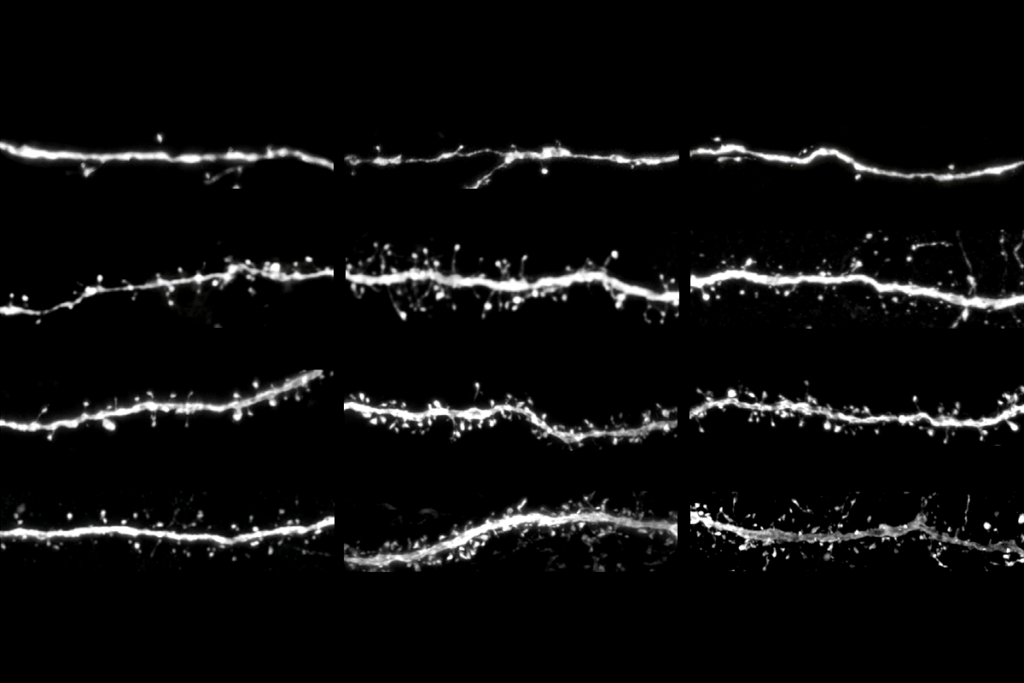

Instead, oligodendrocytes harness mechanical cues—detected through the force-gated ion channel TMEM63A—to determine the proper amount of myelin to deposit, according to a paper from Agarwal’s group published in Neuron last month. The cells stretch more when wrapping around thick axons than around thin ones, the team hypothesizes, which may open the channels more and lead to increased calcium signaling.

The paper corroborates and builds on a growing body of work highlighting TMEM63A’s importance for myelination in mice, zebrafish and humans, says Swetha Murthy, assistant professor at the Vollum Institute, who was not involved in the Neuron paper but reported related findings last year.

K

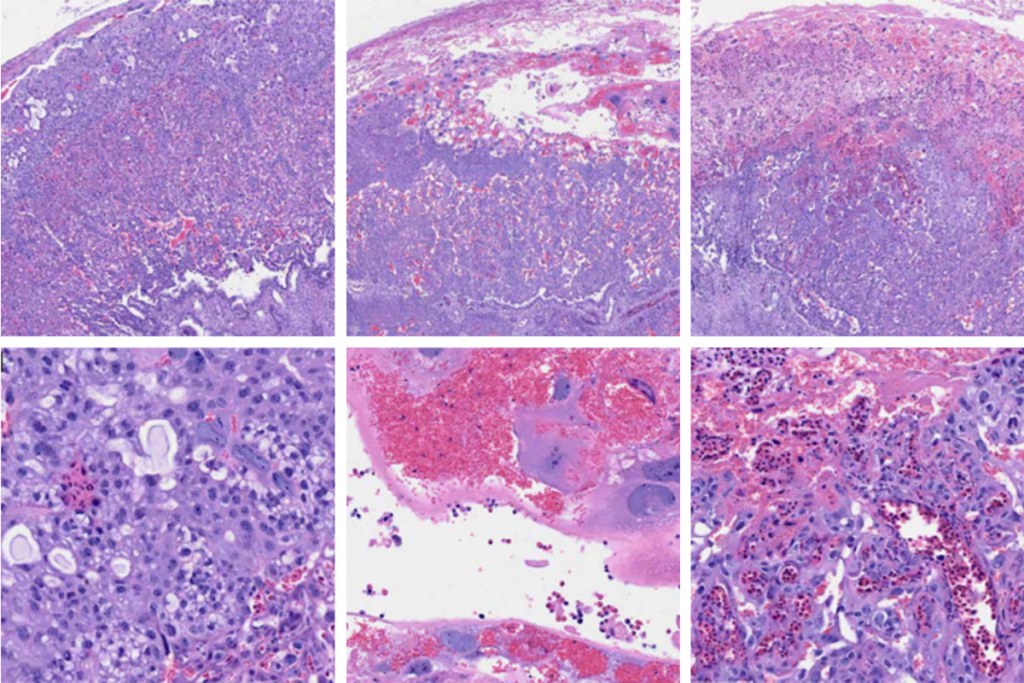

“The geometry is completely messed up,” Agarwal says.

The delayed myelination phenotype resembles that of a rare myelinating disorder called infantile hypomyelinating leukodystrophy 19, which is caused by a loss-of-function mutation in the TMEM63A gene. Infants with the condition show severe hypomyelination at as early as 9 months of age but near-normal myelin by age 2 or 3 years. This link is an “important” demonstration that the function of the channel is “conserved in all vertebrates,” Murthy says.

The TMEM63A channel communicates the size of an axon via calcium signaling, the study demonstrates. Poking oligodendrocytes in a cell culture triggers an influx of calcium, which does not occur in cells without TMEM63A. In developing zebrafish, calcium currents appear specifically within the myelin sheath; TMEM63A knockouts have fewer and shorter bouts of calcium activity than controls.

This pattern implies that as the arms of an oligodendrocyte stretch and wrap around an axon, channels in the arms open and allow calcium into the cell, Agarwal says. Larger axons would stretch the processes more and therefore lead to more calcium signalling.

“I’m fully convinced that TMEM63A is required for myelination,” says Lu Sun, assistant professor of molecular biology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, who was not involved in the work. He adds that it would be nice to see in future work if TMEM63A indeed localizes to the oligodendrocytes’ processes rather than the cell body.

I

This is a curious finding, says Patrizia Casaccia, professor of biology at the City University of New York Graduate Center, who was not involved in the new study. If touching a small axon is typically not sufficient to trigger myelination, she adds, why does removing TMEM63A create a “myelinate-me” signal for those small fibers?

The fact that myelin still develops in the knockout mice, albeit improperly, indicates that additional receptors and cues contribute to other aspects of myelination, Murthy says. “It’s a striking phenotype, but it’s not all gone. The animal doesn’t die, which is the most striking phenotype you would see.”

TMEM63A is the most abundant mechanosensor expressed in mature oligodendrocytes, the new work shows, but it’s possible that other mechanosensors such as PIEZO are involved in other stages of development or can step in to replace TMEM63A, Murthy adds.

“I don’t think there’s one sensor that’s going to do it all,” Murthy says. “Myelination is very important. So nature has somehow come up with the scheme of employing different types of mechanosensors to regulate independent and individual steps.”

Recommended reading

Two primate centers drop ‘primate’ from their name

Post-infection immune conflict alters fetal development in some male mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neurons tune electron transport chain to survive onslaught of noxious stimuli

Protein tug-of-war controls pace of synaptic development, sets human brains apart