Conditions that accompany autism, explained

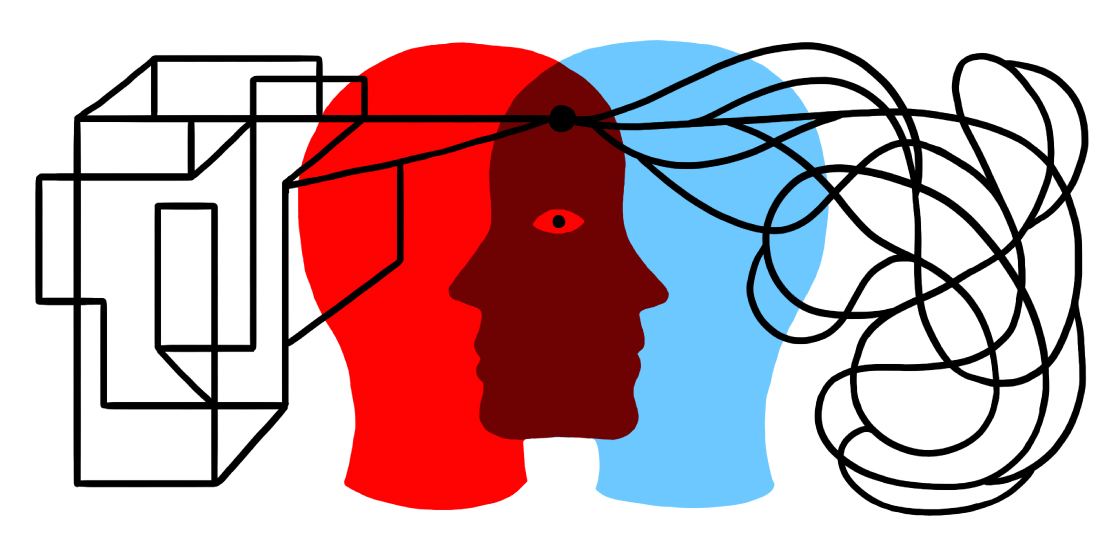

More than half of people on the spectrum have four to five other conditions. Which conditions, and how and when they appear, varies from one autistic person to the next.

More than half of people on the spectrum have four or more other conditions1. The types of co-occurring conditions and how they manifest varies from one autistic person to the next.

These conditions can exacerbate features of autism or affect the timing of an autism diagnosis, so understanding how they interact with autism is important.

Here is what researchers know about the conditions that often accompany autism.

Which traits or conditions commonly accompany autism?

The conditions that overlap with autism generally fall into one of four groups: classic medical problems, such as epilepsy, gastrointestinal issues or sleep disorders; developmental diagnoses, such as intellectual disability or language delay; mental-health conditions, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive-compulsive disorder or depression; and genetic conditions, including fragile X syndrome and tuberous sclerosis complex.

How common are these conditions among people with autism?

It depends on the condition, and estimates vary widely. For instance, between 11 and 84 percent of autistic children also have anxiety2. Similarly, serious sleep problems may affect anywhere between 44 and 86 percent of children on the spectrum3. Differences in diagnostic criteria and other study variables may explain these wide margins. And the age, sex, race and intelligence quotient of the person being evaluated can all influence whether and when they are diagnosed. For instance, autistic black children are more likely than autistic white children to be diagnosed with intellectual disability4. And if a child doesn’t speak, mood disorders may be difficult to detect. Certain conditions, such as anxiety, may also look different in people with autism than they do in other people, adding another layer of complexity.

What’s more, the tools used to identify the conditions may not work as well in people with autism. Researchers are developing autism-specific scales, such as a depression-screening questionnaire, to help solve these diagnostic puzzles.

What can scientists gain from studying these conditions?

Nearly all conditions that accompany autism can have serious effects on well-being. And some have more severe consequences than autism does.

A better understanding of these conditions could improve quality of life for autistic people. For instance, identifying the genes involved could lead to early detection — and treatment — of the conditions.

“We really need to understand the roots of problems in mood and depression, as well as problems of impulsivity,” says Paul Lipkin, director of the Interactive Autism Network at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore. “As we identify better understandings of the neurologic roots of these, we can hopefully develop more and better targeted medical treatments for them.”

Treating a related condition may also ease autism traits. For instance, treating seizures early may decrease cognitive and behavioral problems in children with tuberous sclerosis complex5.

Resolving sleep or gastrointestinal problems may also offer behavioral benefits. Sleep quantity and quality can affect mood and the severity of repetitive behaviors, for example.

How might co-occurring conditions complicate autism diagnosis?

Some autism traits, such as poor social skills and sensory sensitivities, overlap with those of other conditions. For instance, people with autism and those with schizophrenia both have trouble picking up on social cues. When a person presents with one of these common traits, her doctor may simply assign to her the most plausible diagnosis. “It can be very hard to figure out what the root of a behavior is,” says Carla Mazefsky, associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh.

ADHD traits may also mask or be mistaken for those of autism — and delay when a child receives an autism diagnosis.

Autism diagnosis may be particularly tricky in people with intellectual disability or severe language delays.

What can studies of co-occurring conditions reveal about the biology of autism?

Some of these conditions may share biological mechanisms with autism. For instance, a study published this year revealed that gene-expression patterns in the brains of people with autism are similar to those in people with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder6. People with these conditions may also share genetic variants and traits, such as language difficulties or aggression.

In other cases, the relationship to autism may be multifaceted. For instance, about one in three people with autism has epilepsy — and people with epilepsy are at an eightfold risk of autism compared with the general population. The connection may be partly genetic, but it is also possible that early seizures pave the way for certain autism features.

References:

- Soke G.N. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 2663-2676 (2018) PubMed

- White S.W. et al. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 29, 216-229 (2009) PubMed

- Maxwell-Horn A. and B.A. Malow Semin. Neurol. 37, 413-418 (2017) PubMed

- Christensen D.L. et al. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 65, 1-23 (2016) Full text

- Bombardieri R. et al. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 14, 146-149 (2010) PubMed

- Gandal M.J. et al. Science 359, 693-697 (2018) Abstract

Recommended reading

INSAR takes ‘intentional break’ from annual summer webinar series

Dosage of X or Y chromosome relates to distinct outcomes; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Machine learning spots neural progenitors in adult human brains

Xiao-Jing Wang outlines the future of theoretical neuroscience