Editor’s Note

This article has been updated to include comments from additional researchers.

The percentage of Black researchers presenting at neuroscience conferences has increased by only a meager amount since the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020.

This article has been updated to include comments from additional researchers.

Since the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, the proportion of presenters at neuroscience conferences who are Black has increased by only 3 percentage points, according to a new analysis.

The study, published Thursday in Nature Neuroscience, compared the fraction of Black presenters at 18 neuroscience conferences that took place from May 2019 to the end of January 2020 with that at 18 meetings that occurred between October 2020 and the end of May 2021.

Only 3 out of 18 conferences during the earlier time period had any Black presenters, and Black scholars made up just 1.2 percent of the total number of speakers. By the end of May 2021, those figures had risen only marginally: 7 out of 18 conferences had Black presenters, who made up 4.2 percent of the total number.

In other words, the median number of Black speakers at neuroscience conferences was zero for both time periods.

“It was about what I expected, unfortunately,” says study investigator Lewis Wheaton, associate professor of biological sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

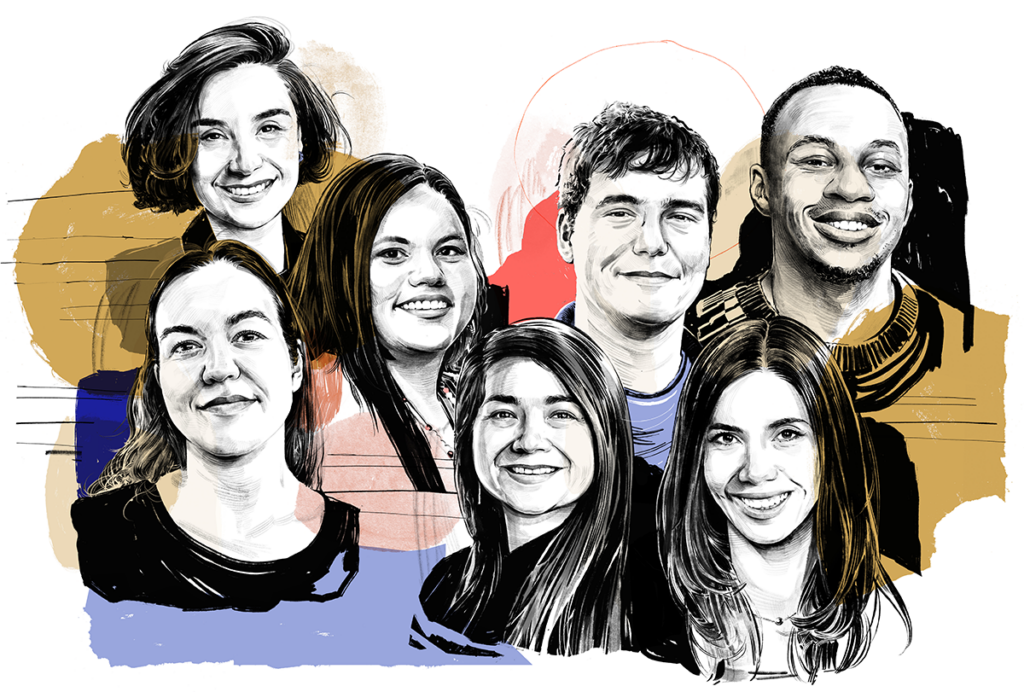

Seeing all those zeros in Wheaton’s data was jarring, but not surprising, says Rackeb Tesfaye, a graduate student in Mayada Elsabbagh’s lab at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, and co-founder of the advocacy group Black In Neuro. The conference data speak to deeper, more systemic issues facing Black researchers, whose work is cited less often in academic literature, who tend to occupy a disproportionately low number of tenured positions and who generally feel less comfortable in academic settings, she says. The data help illuminate the problems and guide discussions, but at some point the neuroscience community needs to commit to making use of the talent and resources that are already available.

As an illustration, Black In Neuro attracted 70 abstract submissions from Black graduate students when it put on its own virtual conference in 2020, after the Society for Neuroscience (SfN) annual meeting was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic, Tesfaye says.

“If a group of trainees is able to do that, it kind of begs the question: What are some of these committees doing?”

The global conversation around race seemed promising in the middle of 2020, Wheaton says. “I saw a lot of people passionate on social media and things like that, and I saw a lot of calls even for change at [the National Institutes of Health].” But as neuroscience conference organizers started putting out requests for presenters in the months that followed, that enthusiasm and introspection largely did not translate into a commitment to racial equity and inclusion, Wheaton says.

To conduct his analysis, Wheaton combed through the selected conference programs and used the profile photos therein or ran a Google Images search to visually identify Black presenters. When in doubt, he contacted individual presenters directly. Among 512 presenters before February 2020, he identified 6 who are Black, and among 479 presenters after October 2020, he found 20 who are Black.

The annual meeting of the American Society for Neurorehabilitation (ASNR), for which Wheaton served as program chair in 2019 and 2021, was one of the top-ranked meetings for Black speaker participation, with 9.7 percent Black speakers before the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests and 18.8 percent after.

ASNR stands out because panel diversity is an active component of the organization’s review criteria, Wheaton says. When demographically homogenous teams of scientists submit proposals for presentations, Wheaton and his fellow organizers ask them to include more ethnic minorities, women or scholars from smaller universities on their projects and resubmit. “It took that active desire to shift things around,” he says.

Wheaton excluded the Society for Neuroscience (SfN), whose annual conference starts today, from his analysis because the program did not clearly separate the speakers from a list of co-authors on a given presentation. But SfN has done a good job of intentionally pushing to increase representation among speakers and participants, says Damien Fair, professor of pediatrics and child development at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, whose team is presenting its research at the meeting.

“The Program Committee and I believe that the brain is an incredibly complex organ and likely requires a diversity of perspectives, skills and approaches to understand,” says SfN 2021 program committee chair Sheena Josselyn, professor of psychology and physiology at the University of Toronto in Canada. “Our unifying goal is to program a vibrant meeting that includes many different voices from all types of neuroscience.”

Part of the problem is that historical and structural inequalities have made the organizations putting on these conferences insufficiently inclusive, so when decisions are being made about the events, Black scientists and scientists from other underrepresented groups are not being properly represented, Fair says. “There aren’t always a lot of Black scholars at the table when talking about Black issues.”

The conferences are “the parades that show that the emperor has no clothes, says David Mandell, professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. “We can talk all we want about diversity, but until we are more aggressive and inclusive in our recruiting efforts and the support we provide to marginalized scientists, from undergraduate through faculty, we won’t have diversity.”

Inclusion efforts are not just about fulfilling criteria, but about ensuring that scientists have equal access to career opportunities, Wheaton says. “If Black scientists are not invited to give platform presentations, you’re keeping opportunities away from those Black people to be able to disseminate their science nationally and internationally.”

Missing out on these opportunities prevents Black scientists from meeting potential mentors or mentees, connecting with new collaborators and exposing their work to potential grant reviewers, Wheaton says. “If you’re not actively doing it, whether you intend or not, you are actively suppressing the careers of those scientists, including people that look like me.”

For many Black scientists, the lack of racial equity and inclusion may lead to self-doubt, angst and chronic feelings of isolation, and it can deprive them of or stagnate opportunities to develop strong networks, says Michelle Antoine, section chief on neural circuits at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, whose team is presenting at SfN. “Such connections are very valuable in promoting intellectual exchange, sharing and amplifying access to resources, as well as the training needed to give the present and future generations the tools to be successful.”

More diverse conferences and labs grant more opportunities to more researchers. And increasing the diversity of thought and background in a lab improves the quality of the science, Fair says.

“The pure variability and diversity of ideas will lead to better questions and answers to the actual scientific discipline itself,” he says. “We’ve known this for years.”

This article has been updated to correct David Mandell’s title.