How pragmatism and passion drive Fred Volkmar—even after retirement

Whether looking back at his career highlights or forward to his latest projects, the psychiatrist is committed to supporting autistic people at every age.

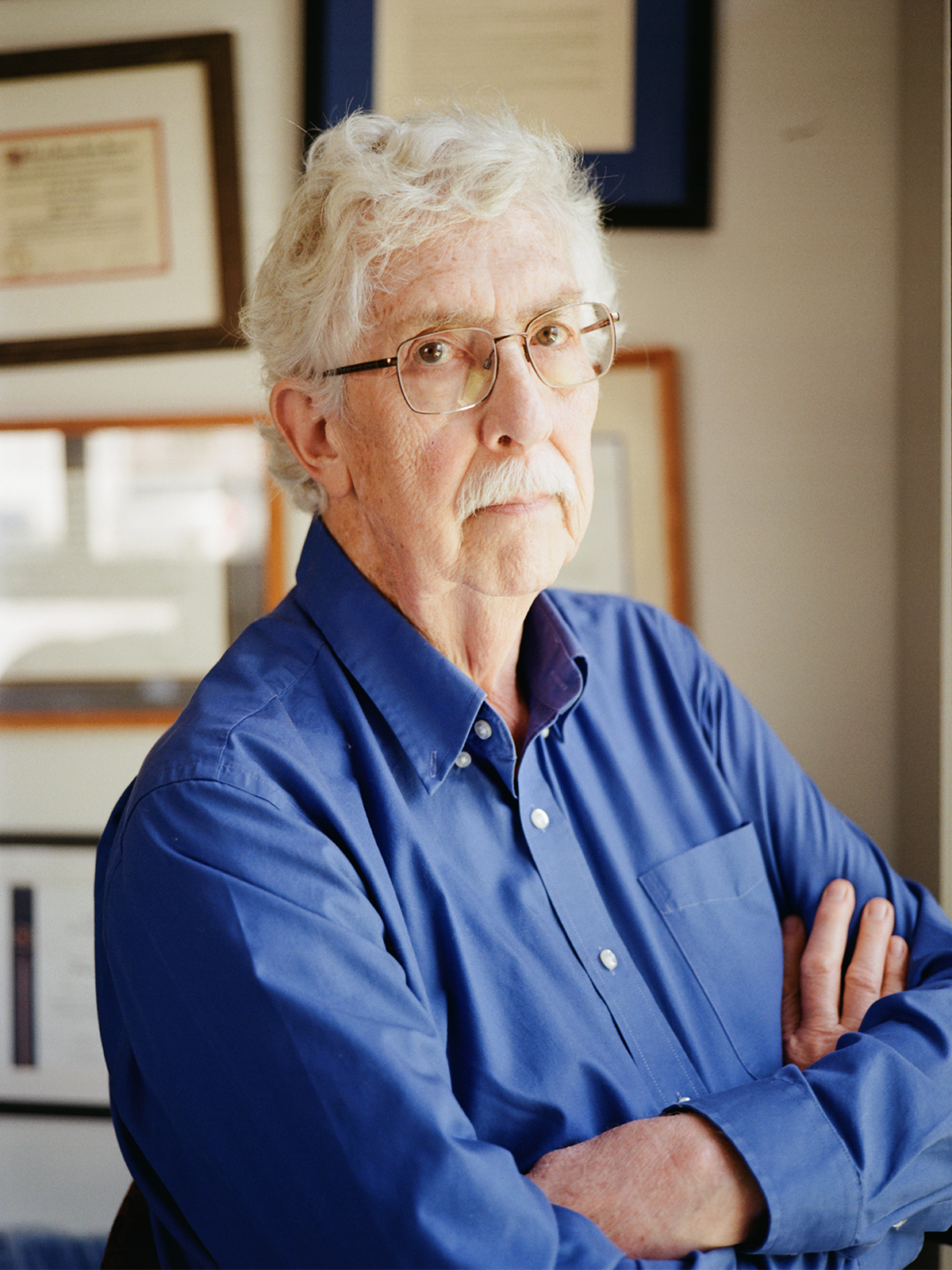

Sitting in his sunny office at Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU), casually dressed in a plaid shirt and khakis, Fred Volkmar gives the impression that he has all the time in the world—though that is far from the truth.

His shih tzu, Charlie, visiting for the day, reposes in a nearby armchair exuding a similar spirit. Charlie’s fuzzy white muzzle is a near match to Volkmar’s wavy hair and bushy mustache.

In October, Volkmar retired after 44 years at Yale University’s Child Study Center, including 10 as director of the Autism Program, and moved from active faculty as Irving B. Harris Professor of Child Psychiatry, Pediatrics and Psychology to emeritus status. But he holds an endowed chair in special education at SCSU—the school’s only named chair, in fact—from whence he continues to direct a wide array of activities.

In addition to several writing and editing projects, he oversees a program that gives local autistic high school students a taste of college at SCSU, and he continues to teach his popular undergraduate course on autism at Yale—reputedly the first course of its kind when Volkmar introduced it in 1984. And together with one of his recent undergraduate students, he published findings in March on a model program to help young autistic adults interact with police during traffic stops—a nontrivial issue, he notes, because “driving is key to employment.”

Volkmar has long been a towering figure in the field: an influential and observant clinician, a mentor to generations of autism researchers and a strong advocate for people on the spectrum and their families. “There aren’t that many places where the researchers are actively involved in the clinic,” says Catherine Lord, George Tarjan Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry and Education at the University of California, Los Angeles, who has worked alongside Volkmar on many projects, committees and publications for decades, “and Fred was.”

Volkmar has authored hundreds of research papers and dozens of books on autism—including several for laypeople. Since 1987, he has edited every edition of the Handbook of Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders, the fifth edition of which he is busy editing. And he was editor-in-chief of the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders from 2007 to 2022.

Perhaps most famously, Volkmar led the committee of the American Psychiatric Association that modernized the definitions and diagnostic criteria for autism in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published in 1994—though in 2012 he made waves with his public critique of the fifth edition’s approach to autism and his decision to leave the DSM-5 work group.

For Volkmar, a foundational principle is pragmatism—a steadfast focus on strategies that he believes will be helpful to autistic people in their daily lives. That value underpinned some of his objections to the DSM-5, and it remains central to his thinking today.

“Fred was always ‘big picture’ and very practical,” says Giacomo Vivanti, associate professor at the A.J. Drexel Autism Institute, who trained under Volkmar at Yale.

“For any idea, he would ask: How is this going to be beneficial for the lives of autistic people or their parents? There was no attempt to encourage scholarship for the sake of scholarship.”

V

olkmar started life in a family of modest means in the tiny town of Sorento, Illinois. He was admitted to a select program of small classes at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and found his calling almost immediately. “I got into a Psych 101 class with 20 students, a teacher and a TA, as opposed to 600 students,” he recalls.Smitten by child psychology in particular, he began volunteering at a school that served children with autism—his first encounter with the condition that would become his lifelong focus. Volkmar’s senior thesis on mouse brain plasticity was overseen by the late, trailblazing neuroscientist William T. Greenough, who helped get the work published in Science. “We had some very nice data—and, by gosh, he made me first author,” Volkmar remembers.

Volkmar credits that paper with opening the door to Stanford University, where he earned both his M.D. and an M.A. in psychology. From there, he followed his interest in autism to Yale, to work with Donald J. Cohen, another pioneer in the field.

At Cohen’s suggestion, Volkmar began gathering clinical experience at Benhaven School, a local school for children with autism, eventually serving as chief psychiatrist. Volkmar also got to know residents at Benhaven’s home for adults. “I ended up being the psychiatrist for that house for 40 years.”

That hands-on experience helps explain why Volkmar was an early proponent of investigating autism in adults as well as children. “He had a long-standing interest in development across the lifespan before studies of adults with autism became popular,” Lord points out.

Volkmar never forgot the opportunities he received early in his career and has paid it forward many times. “Fred is extraordinarily good at including young researchers and providing them with opportunities, trust and loyalty,” says Roald Øien, professor of special education and developmental psychology at the Arctic University of Norway, who earned his doctorate under Volkmar at the Yale Child Study Center and retains an adjunct appointment there. “Mentorship is a big part of what he’s offered to the field.”

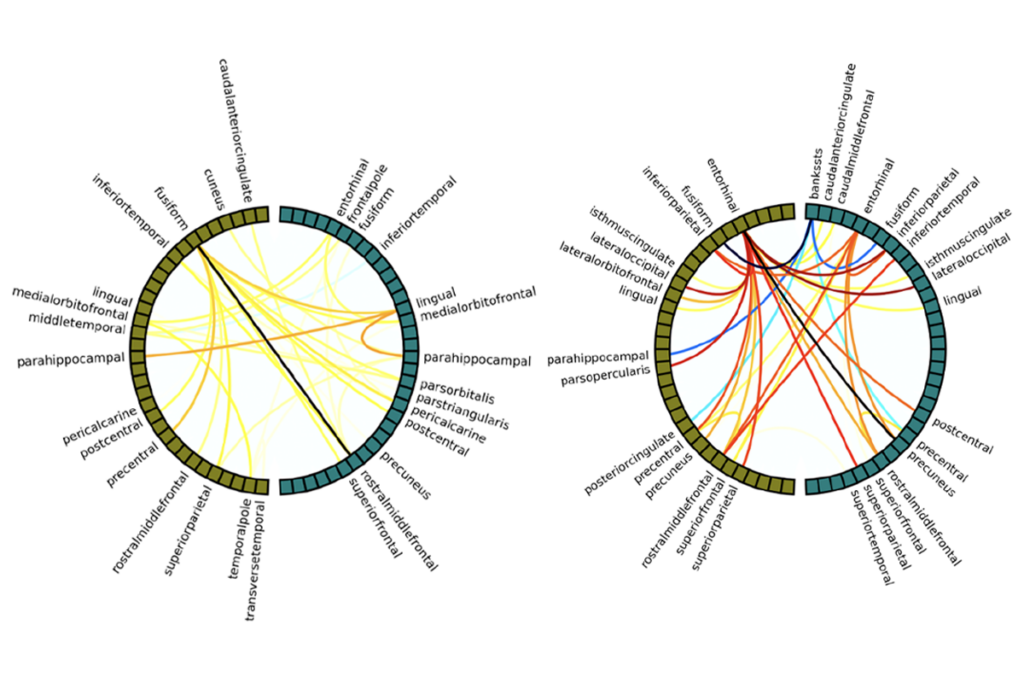

Volkmar’s research is wide-ranging, but he has been particularly interested in how autistic people process social information. In the early 2000s, he and his colleagues at Yale found that people with autism—unlike their neurotypical peers—process images of faces in the same brain regions where objects are processed and that they focus less on people’s eyes during social interaction than do neurotypical people.

When he discusses such findings with teachers and therapists, Volkmar suggests that instead of training autistic children to make eye contact, “we should take a step back and ask how we could give them information that would be more helpful. Maybe they’re avoiding the eyes.”

Such efforts to see things from an autistic child’s perspective led Volkmar and several Yale colleagues to investigate puppets as a tool to improve social engagement. In a 2021 study, they discovered that children with autism looked at puppet faces as much as neurotypical children did, hinting that puppets might be useful in social-skills therapy.

V

olkmar’s deep clinical experience with autistic people of all ages and abilities guided his thinking about the DSM. Under his leadership in the 1990s, the DSM-IV work group defined diagnostic criteria for autism subtypes, such as Asperger syndrome and pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS). And, for the first time, it aligned them with the criteria in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD).“Fred was very instrumental in making the DSM-IV rational,” Lord says. “He worked with the [DSM] group both to get it to be in sync with ICD-10, which was really important, and also to represent the range of autism.”

Volkmar joined the autism work group for the fifth edition of the DSM, but he did not lead it and objected to the updates the group proposed. Having helped define subtypes of autism, Volkmar disagreed with a plan to fold these categories into a single autism spectrum.

His principal concern was that autistic people with low support needs would no longer meet the diagnostic criteria and would lose needed services. He went so far as to conduct a study, also controversial, that aimed to demonstrate this risk.

His second objection was that the committee commissioned no field studies to support their proposed changes, although other research was done. Volkmar, by contrast, had organized international field studies to help define diagnostic categories for the DSM-IV.

Unhappy with the new direction, Volkmar quit the work group, as did a few others. Lord says she agrees about the field trials but that it was “a shame” Volkmar quickly resigned rather than staying involved to argue his case. Volkmar’s concerns about the new criteria missing people on the low-support-needs end are still under debate. Edwin Cook, director of child psychiatry at the University of Illinois Chicago, served on the DSM-5 committee with Volkmar and remains a frequent and admiring collaborator. He appreciated Volkmar’s concerns at the time, he says, but suspects that “if anything, moving to a spectrum included more people.”

I

n Volkmar’s 40-plus years in the autism field, probably the most consequential developments, he says, are earlier detection and better, more evidence-based interventions. “When I first got into the field, a 4-year-old was a young child with autism. These days, we’re seeing babies,” he says.Earlier diagnosis and treatment have led to better outcomes for some two-thirds of children with autism, he says. But that leaves “a hard core of 30 percent” who, despite having access to good programs, don’t do well. “We don’t understand why, so then the problem is, what can we do for them?”

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Volkmar says he worries that “kids with autism are like high school graduates,” even when they have college degrees. “They get menial jobs, and half of those who want jobs don’t get jobs.”

These ongoing challenges were part of the conversation at Volkmar’s retirement party at the Yale Child Study Center last October.

“We were talking about how the science of intervention has evolved a lot,” Vivanti recalls. “Yes, Fred said, but for certain populations, such as older individuals who are not speaking, the science is pretty much the same as it was years ago. People are not addressing that gap.”

It was vintage Volkmar: a clear-eyed focus on the unmet needs of the autism population and on the hard work ahead.

Correction

Recommended reading

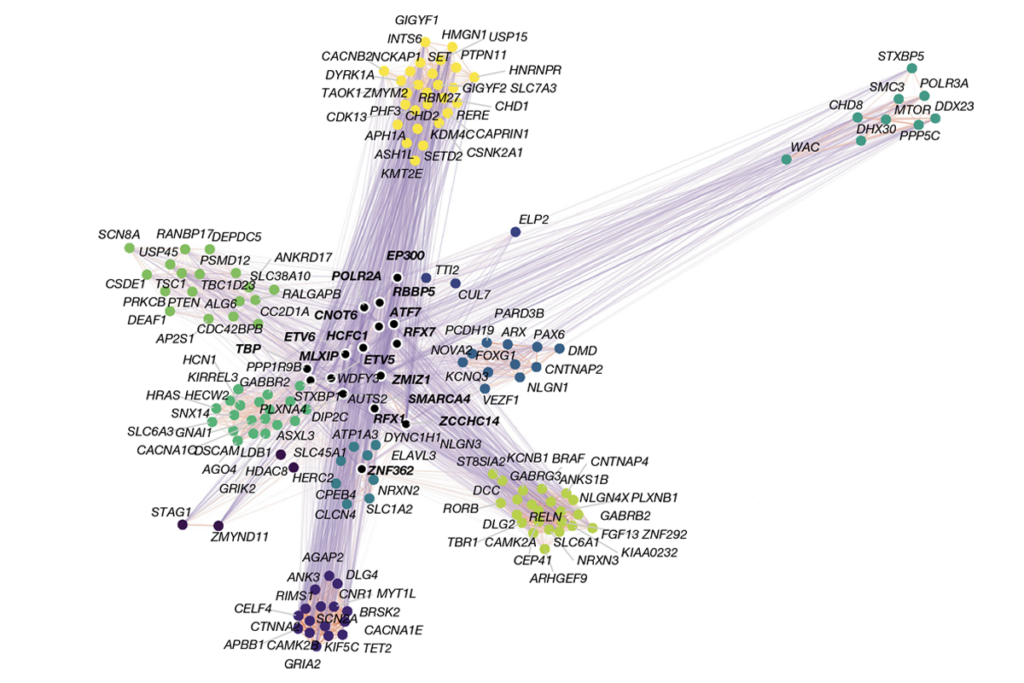

Organoid study reveals shared brain pathways across autism-linked variants

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

Explore more from The Transmitter

Emotional dysregulation; NMDA receptor variation; frank autism

Vasopressin boosts sociability in solitary monkeys