Q&A with Luca Santarelli: Targeting neuronal connections

Luca Santarelli, head of neuroscience at Roche, explains why he is optimistic that pharmaceutical companies can overcome the obstacles in autism drug development.

When Swiss pharmaceutical giant Roche gathered a cadre of autism experts in April for the Roche Translational Neuroscience Symposium, one message soon became clear: The disorder is even more complex than scientists had thought.

Results published in the past few months suggest that hundreds of genes are likely to be involved, making it difficult to identify the core molecular deficits. That in turn creates a challenge for drug developers, who don’t know which mechanisms to target.

But Luca Santarelli, head of neuroscience at Roche, is optimistic that pharmaceutical companies can surmount this obstacle. He points out that many of the autism genes discovered thus far play a role at the synapse, the junction between neurons, narrowing the field for drug makers. Existing drugs might even prove effective, he says, if we can figure out who is most likely to benefit from them.

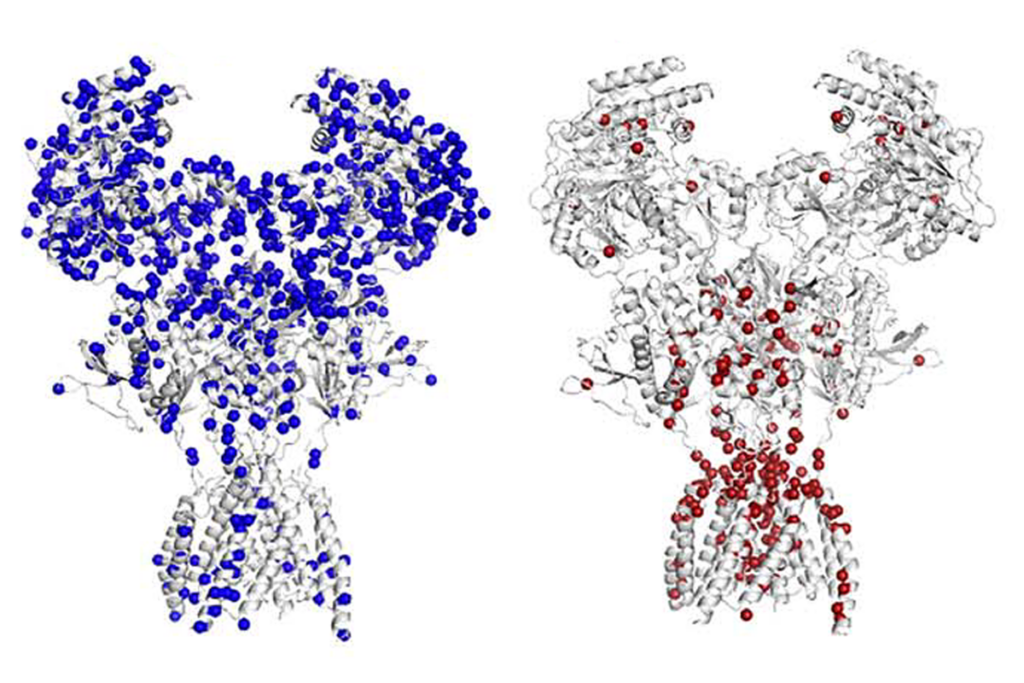

Roche is developing at least two compounds for autism and related disorders. The first is a compound for fragile X syndrome that blocks a receptor called mGluR5, and the second is an antagonist of the V1A vasopressin receptor, which is thought to modulate emotional and social responses.

Roche is also heading a multinational partnership between academia and industry, funded by the European Union, to speed up basic and clinical research in autism. Santarelli tells SFARI.org why he thinks drug development for autism is at a turning point.

SFARI.org: Autism has long been ignored by drug developers. What prompted Roche’s interest in this disorder?

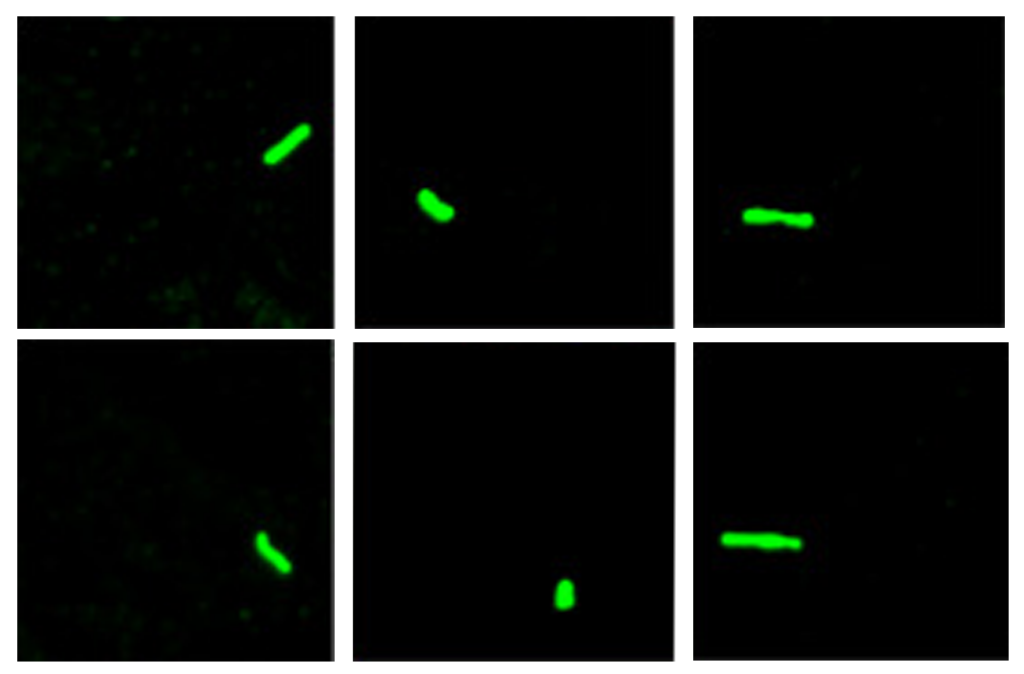

Luca Santarelli: Autism is becoming amenable to drug treatment. We have animal models with the same genetic deficit as in humans and with a full set of symptoms, from molecular changes to behavior. We have the ability to model cell and molecular changes in patients with induced pluripotent stem cells. Proof-of-concept research in schizophrenia and Timothy syndrome has shown you can identify targets from the patients themselves.

We view our commitment to neurodevelopmental disorders as a sign of willingness to take risks and be more innovative. We have learned from our legacy in oncology over the past decade, which has helped us focus more on disease mechanisms than on phenomenology. The past decade of oncology success has proven the importance of understanding the mechanisms of disease.

SFARI.org: How do we get at the mechanisms underlying autism?

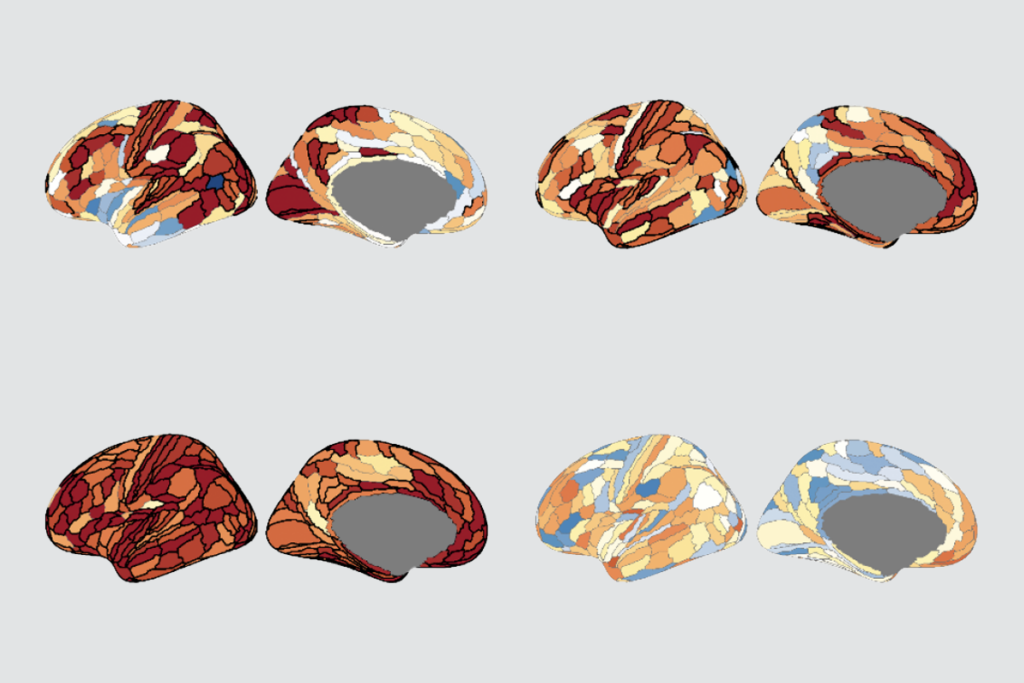

LS: Genetics is showing us the way as far as what type of biology is altered in autism. We are also starting to see some activities that better define the clinical side of the disorder, such as from functional and anatomical imaging. But I think those are really in infancy, especially when it comes to the ability to standardize across different sites.

SFARI.org: Is the complexity of autism a major barrier to drug development?

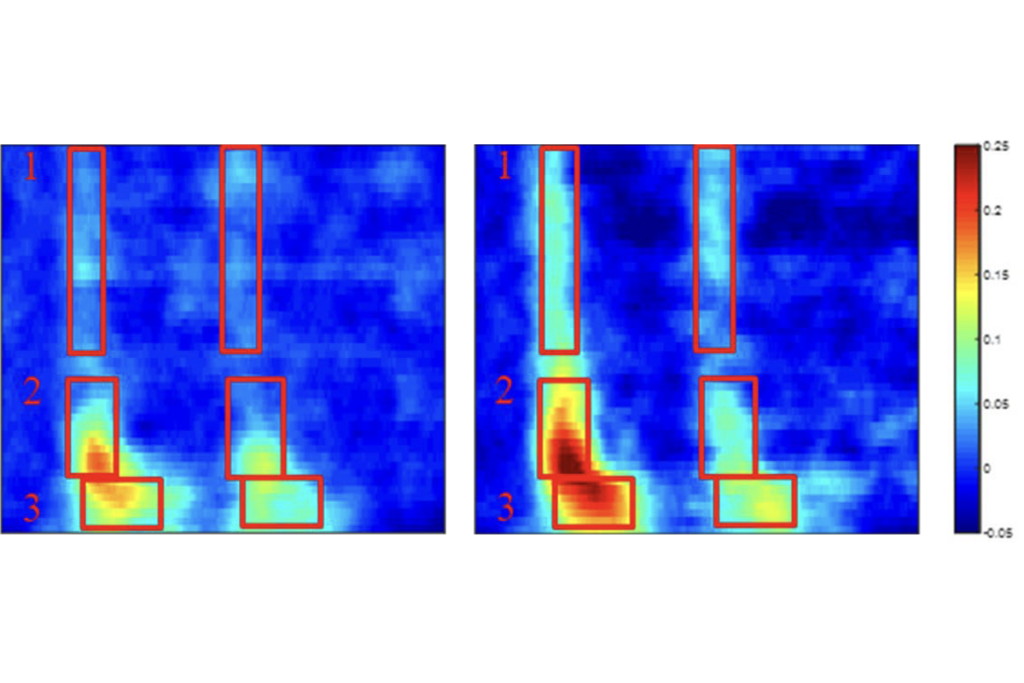

LS: Understanding everything from the bottom up is very challenging. For example, you can’t make mouse models for all the genes that are linked to autism. As we think about drug discovery, we’ll probably have to examine a number of models until we identify clear patterns. Perhaps there are certain clusters of pathophysiology that underlie the disease. If we can reduce the problem to those clusters, it becomes more tractable from a pharmaceutical perspective.

SFARI.org: What are the most promising drug targets for autism?

LS: From a pharmaceutical standpoint, we can’t develop drugs for all the rare mutations linked to autism. So I think that reduction to the synaptic level is a great opportunity. The synapse has a number of druggable targets that can only be modified in certain ways. If we know what synaptic defects define individuals, I think we’re in good shape.

The real question is, how do you know what patient has what synaptic effect? We likely already have drugs for autism sitting on our shelves; we just don’t have the right patients to give them to.

Recommended reading

Protein interactions important to SYNGAP1-related conditions; and more

Autism-linked copy number variants always boost autism likelihood

New findings on Phelan-McDermid syndrome; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Anti-seizure medications in pregnancy; TBR1 gene; microglia

Vasopressin boosts sociability in solitary monkeys