Questions for Amaral, Halladay: Boosting brainpower

A new network of brain banks aims to collect and disburse tissue donations to U.S. autism researchers.

Autism is a complex and heterogeneous condition, and understanding it takes brains —literally.

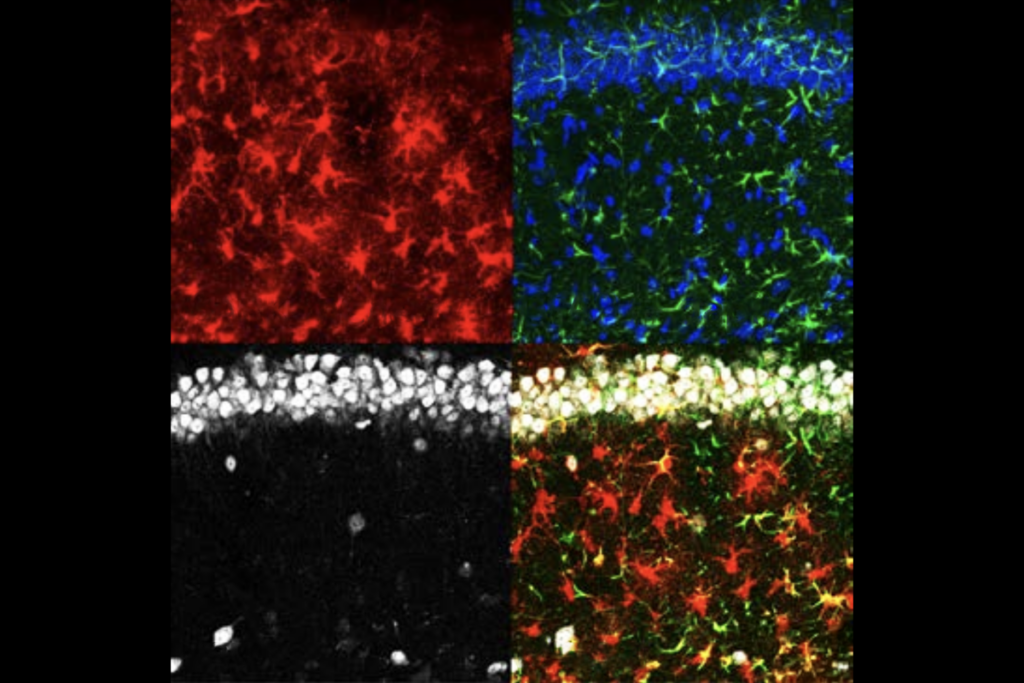

Studying postmortem brain tissue from people with autism can provide important clues about the biology of the condition and pave the way to treatments. But to do such experiments, researchers rely on donations from families affected by autism.

With this need in mind, a team of researchers created Autism BrainNet — a network of brain banks that collects donations from anywhere in the U.S. and parts of the U.K. The initiative’s leaders aim to ensure that donated tissue is put to the best possible use (the effort is funded in part by the Simons Foundation, Spectrum’s parent organization). A mammoth outreach effort, coordinated by the Autism Science Foundation (ASF), boosts awareness of the need for brains.

We asked Autism BrainNet director David Amaral, distinguished professor of psychiatry at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis) MIND Institute, and Alycia Halladay, chief science officer of the ASF, about BrainNet’s role in advancing autism research.

Spectrum: Why did you establish Autism BrainNet?

David Amaral: From 2003 to 2011, a special-interest group focusing on postmortem brain studies gathered each year at the International Meeting for Autism Research. Instead of talking about the exciting research being done, we would complain about the lack of postmortem brain tissue. It had become a crisis for autism research, slowing the pace of genetic research and hobbling attempts to identify the underlying biology of the condition.

In 2010, Cynthia Schumann and I started a pilot program at the MIND Institute called Brain Endowment for Autism Research Sciences. The program was based on the principle that the research community needs to be engaged in the effort to collect brains, and that families needed to feel comfortable donating the brain of a loved one. But we realized we needed to scale up our efforts, so we outlined our vision for a national network to collect autism brain donations and circulated it to leaders at funding organizations.

Eventually, Autism Speaks and the Simons Foundation agreed to support Autism BrainNet. We now have four tissue collection ‘nodes,’ located at the UC Davis MIND Institute, the University of Texas Southwestern, Beth Israel Hospital and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. We also have one international site at Oxford University in the U.K. Any brain donated to any of these sites goes into a consolidated collection that will be distributed to researchers through a centralized process.

S: What are the biggest hurdles in setting up a program of this sort?

DA: One big challenge is getting the word out that brain donations are key to understanding autism, so that we can move toward effective treatments. We also need to get the word out on how to donate. We have heard from families that were interested in making a brain donation that they couldn’t find information about how to do it. Because a donation needs to be made relatively quickly to allow for the highest-quality research, it’s important that families and individuals affected by autism discuss the possibility of brain donation during life.

Alycia Halladay: I think the biggest challenge is what we call the ‘ick factor.’ People can get behind research, and they understand why we need to study brain tissue, but the whole idea of removing the brain is not appealing. People don’t want to think about their child’s death.

S: How will you publicize this program?

AH: We developed the ‘It Takes Brains’ campaign to encourage families and individuals with autism to learn more about why tissue donation is so important, and to register for additional information.

ASF works closely with Dr. Amaral and all four nodes to identify opportunities to speak to community members and explain the science in ways that are meaningful to families. It is incredibly important for families and individuals affected with autism to see why this is an important initiative and learn how they can get involved.

S: What does it mean for a family to join Autism BrainNet?

AH: Joining the Autism BrainNet Registry (at TakesBrains.org) is not a binding agreement but a declaration of interest. It means that you become part of Autism BrainNet and receive quarterly newsletters that provide updates about the program, as well as summaries of studies and what they might mean for people with autism. We have about 3,000 registrants and hope that another 1,000 or so register each year. People who register are superheroes in our book. They want to be part of scientific progress.

S: What types of brains do you need?

DA: We encourage donation from anyone with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. This includes individuals with related disorders, such as fragile X syndrome, duplication of the 15q11.2-13.1 chromosomal region, tuberous sclerosis and epilepsy. Because it is essential for researchers to have a control match for each of our donors with autism, we encourage donations from people who are not affected by autism as well.

S: How many brains do you aim to collect?

DA: Autism is an incredibly heterogeneous disorder. This means we need to collect a large number of brains to get a complete picture of its biology. We have collected dozens of brains in the past, but we really need hundreds. We hope that Autism BrainNet will accomplish this goal.

S: How do you plan to allocate the donated brain tissue?

DA: An independent panel of scientists reviews every application for tissue. This process is entirely transparent and no one has special access to the tissue — not even the node directors. The goal is to enable the largest amount of autism research by the most highly qualified researchers worldwide.

Rather than one or two scientists studying a particular brain, we are aiming for dozens or even hundreds of researchers to use the tissue. Importantly, all data will come back to Autism BrainNet and will be posted on our website for investigators worldwide to access.

S: What have you discovered so far?

DA: I have been surprised and encouraged by the fact that our most ardent supporters are the next of kin of many of our donors. Family members tell us that making a brain donation that will support research leading to better lives for children now and in the future helps with their grieving process. It is a positive facet of an otherwise difficult time in the family’s life.

Recommended reading

INSAR takes ‘intentional break’ from annual summer webinar series

Dosage of X or Y chromosome relates to distinct outcomes; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

Null and Noteworthy: Neurons tracking sequences don’t fire in order