Long-standing theoretical neuroscience fellowship program loses financial support

Funding from the Swartz and Sloan Foundations helped bring physicists and mathematicians into neuroscience for more than 30 years.

A program that has funded more than 100 theoretical neuroscience postdoctoral fellows at more than a dozen institutions is ending this year.

After more than three decades, the Swartz Foundation is shuttering the program due to “financial constraints,” according to an email, which was reviewed by The Transmitter, from the foundation to a grantee. Since 2012, the foundation has had a negative annual income and its assets have been steadily declining, according to its form 990 tax filings. The Swartz Foundation did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The fellowships helped seed a field, says Paul Miller, professor of biology and director of the Swartz Center for Theoretical Neuroscience at Brandeis University. “When they started, there were just a handful of places that would do computational neuroscience,” he says. Now, “every major research university in the world probably has a professor with computational neuroscience skills.”

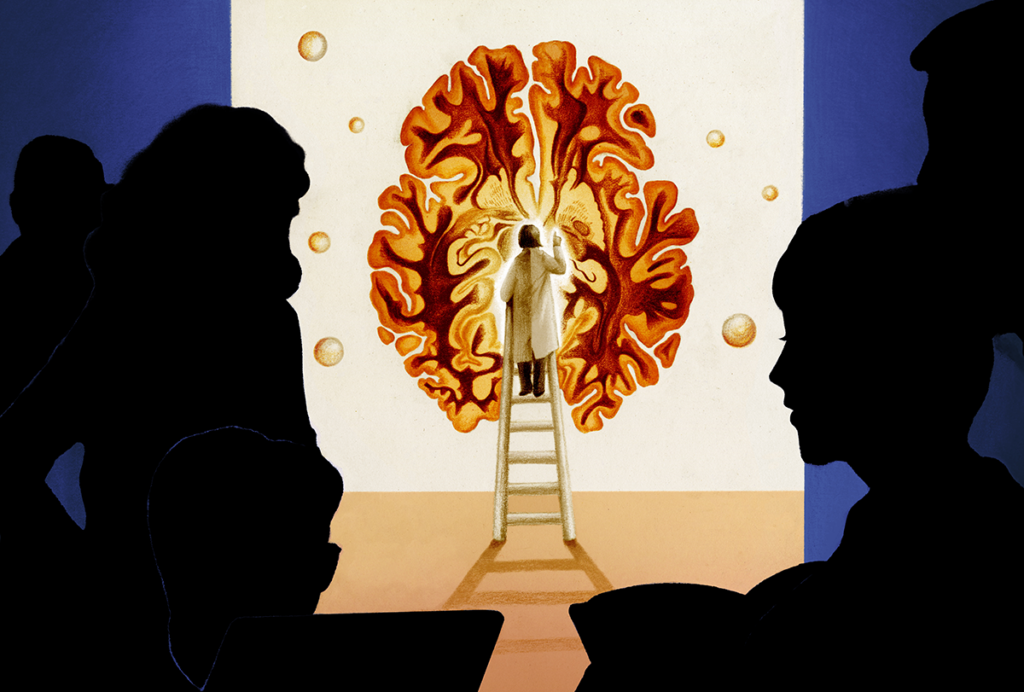

The foundation’s origins trace back to the early 1990s, when neuroscience was “long on experimentalists and short on theorists,” says J. Anthony Movshon, professor of neural science and psychology at New York University. In mature fields, “theorists tell experimentalists what to measure,” Movshon recalls a colleague telling him, whereas in immature fields, “experimentalists tell theorists what to model, which is backwards in terms of how we imagine the science is supposed to work.”

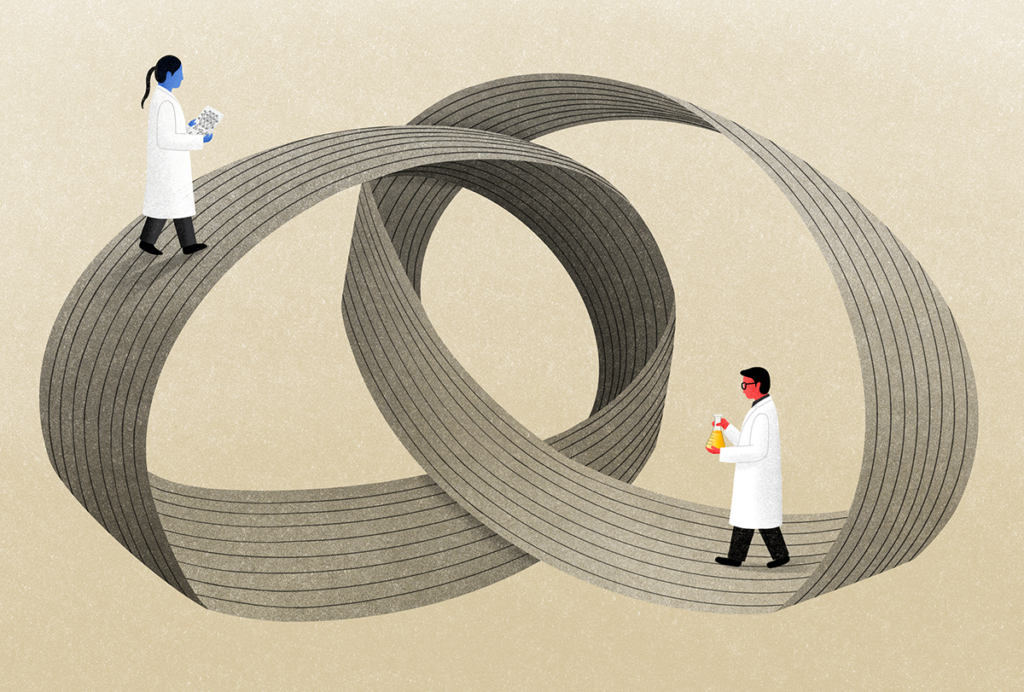

Charles Stevens, then a professor at the Salk Institute, had an idea for solving this problem: recruit people trained in mathematics, engineering, physics or computer science and convert them into theoretical neuroscientists by embedding them in experimental neuroscience labs. Stevens approached Hirsch Cohen, then a grant officer at the Alfred P. Sloan foundation, a science and engineering grant-making nonprofit, with his idea.

In 1994, the Sloan Foundation funded theoretical neuroscience centers at five institutions: the Salk Institute, Brandeis University, the California Institute of Technology, New York University and the University of California, San Francisco. The foundation split $7 million among the centers over the course of three years and renewed the grants in 1997 for another three years.

The Sloan Foundation typically funds new projects for a few years rather than support them in perpetuity, Movshon says, so in the early 2000s Cohen persuaded Jerome Swartz, an engineer who created the handheld barcode scanner and had become interested in computational neuroscience, to take over the program. His foundation, the Swartz Foundation, eventually added centers at six other institutions and funded fellowships for individual students at several others.

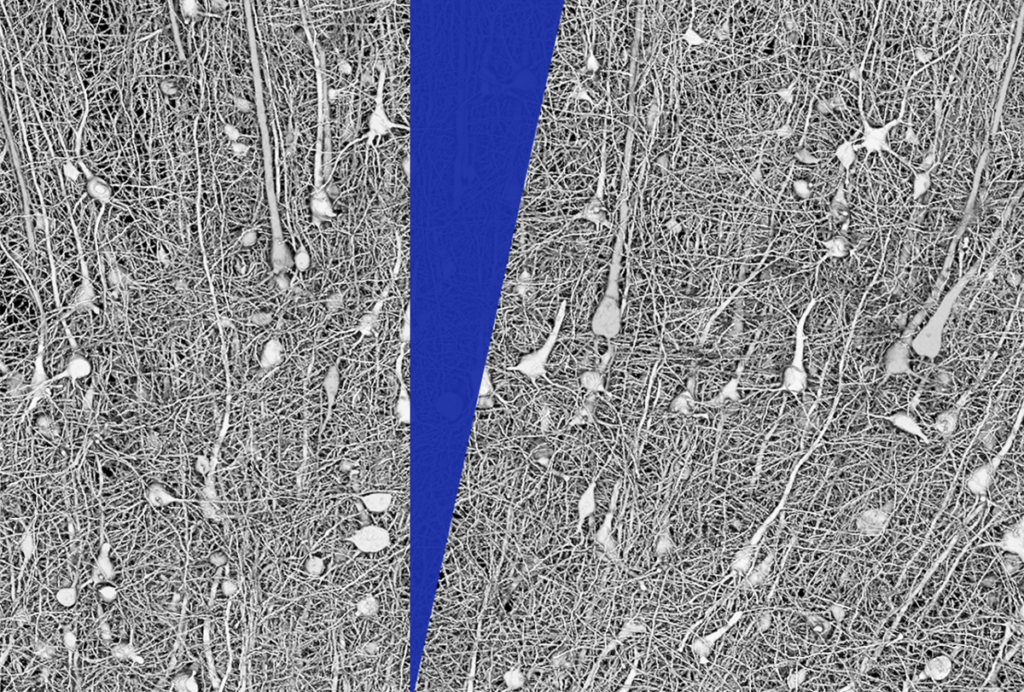

S

ome of the centers used the funding to hire faculty, but the bulk of it went toward recruiting postdoctoral researchers who were trained in physical sciences. Scientists with a mathematical or physics background are well equipped to grapple with neuroscience’s complex concepts and problems, but they need time to learn enough biology so that the models and theories they develop adhere to biological realities, says Eve Marder, university professor of biology and founding director of the Swartz Center for Theoretical Neuroscience at Brandeis University.“In a sense, you want the biological intuition of a really good biologist or biophysicist,” Marder says, “and the quantitative tools that a really well-trained physicist or mathematician might have.”

That’s exactly what the centers enabled, Miller says. Because the trainees had their own funding, it granted them time to get up to speed on biology and familiarize themselves with experimental labs, whereas a principal investigator funding a postdoc through their main grant needs “to hire someone who’s going to be productive right away.” As a result, the Sloan fellows learned “how neuroscience actually functions in the wild,” Movshon says.

Ann Kennedy credits the fellowship as part of the reason she secured a postdoc position in David Anderson’s lab at the California Institute of Technology. “The fact that I could have this external source of funding helped him hedge his bets a bit and try things out without having to put his funding on the line,” says Kennedy, now associate professor of neuroscience at the Scripps Research Institute. Plus, because the funding wasn’t tied to an experimental grant, it gave the fellows “a little room to breathe and think about things in the abstract,” which is important, yet rare, she adds.

T

he centers grew a “critical mass” of theorists at each institution, Miller says. The fellowships were open to people from any country, which “created an international field,” Marder says.Each year, faculty and fellows from all of the centers gathered for a scientific meeting to discuss current work and debate new ideas, such as the nature of working memory, recalls Xiao-Jing Wang, professor of neural science at New York University. “Discussions at those meetings were quite interesting and important for the field.”

During the scientific talks, Swartz sat in the front row with index cards in his shirt pocket, some filled with questions and some empty for taking notes, recalls Jessica Cardin, professor of neuroscience and co-director of the Swartz Center at Yale University. He asked “fabulous, really on-point questions.” Swartz was a “real cheerleader” for the field, Marder says.

The timing of the loss is particularly difficult, as it comes while the United States faces a “devastating destruction of science funding,” says Anthony Zador, professor of neurosciences at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory. But the original goals of the centers have largely been achieved: In the 1990s, neuroscientists often complained “that theorists were completely out of touch with experimental data,” Zador says. Today, “I very rarely hear that.” So while the loss is sad, it’s “maybe almost sad in the way that seeing your children go off to college would be sad.”

Recommended reading

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models

Breaking the barrier between theorists and experimentalists

Two primate centers drop ‘primate’ from their name

Explore more from The Transmitter

NIH cuts quash $323 million for neuroscience research and training

Multisite connectome teams lose federal funding as result of Harvard cuts