Aging neurons outsource garbage disposal, clog microglia

Degradation-resistant proteins pass from neurons to glial cells in a process that may spread protein clumps around the brain, according to a study in mice.

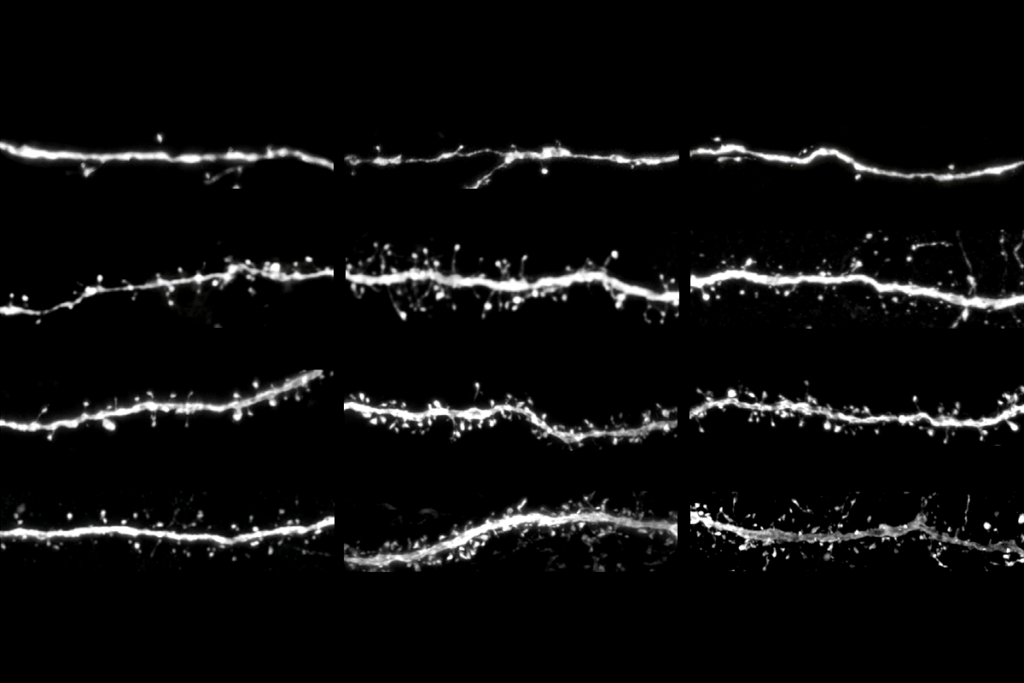

Synaptic proteins degrade more slowly in aged mice than in younger mice, a new study finds. Microglia appear to unburden the neurons of the excess proteins, but that accumulation may turn toxic, the findings suggest.

To function properly, cells need to clear out old and damaged proteins periodically, but that process stalls with age: Protein turnover is about 20 percent slower in the brains of older rodents than in youthful ones, according to an analysis of whole-brain samples. The new study is the first to probe protein clearance specifically in neurons in living animals.

“Neurons face unique challenges to protein turnover,” says study investigator Ian Guldner, a postdoctoral fellow in Tony Wyss-Coray’s lab at Stanford University. For instance, their longevity prevents them from distributing old proteins among daughter cells. And unlike other proteins on the path to degradation, neuronal components must first navigate the axon—sometimes traveling as far as 1 meter, Guldner says.

In the new study, Guldner and his colleagues engineered mice to express a modified version of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase—a component of the protein synthesis machinery—in excitatory neurons. Every day for one week, mice of different ages received injections of chemically altered amino acids compatible only with that mutant enzyme. Neurons used the labeled amino acids to replenish proteins, enabling the group to track how quickly those proteins degraded over the subsequent two weeks.

“The achievement lies in the technical advance, namely by being able to look at protein degradation and aggregation specifically in neuronal cells,” says F. Ulrich Hartl, director of the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, who was not involved in the study.

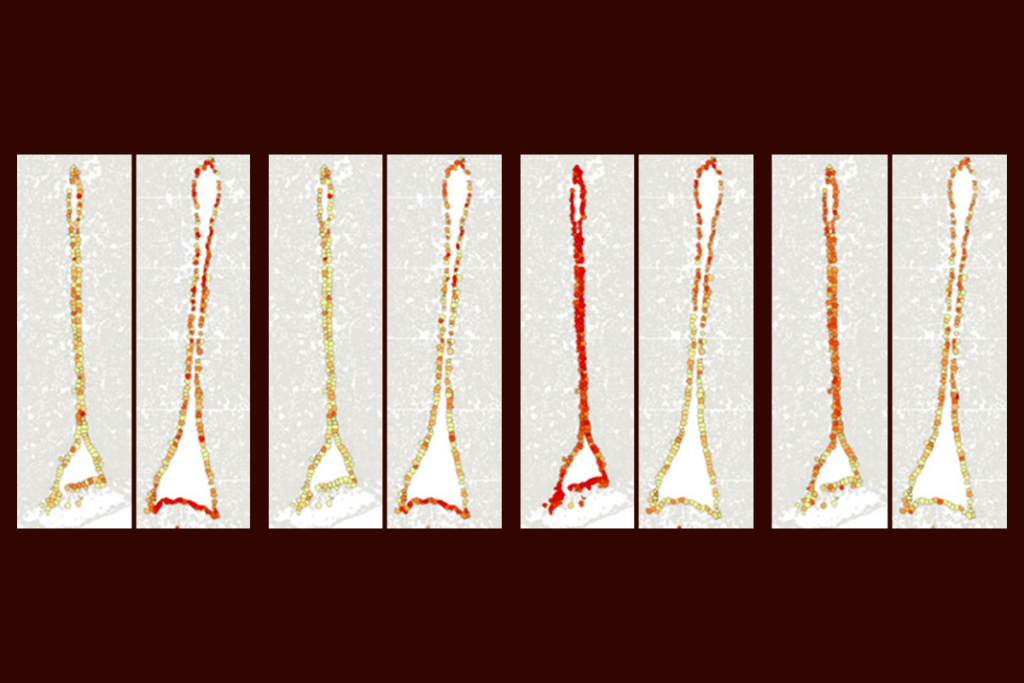

In excitatory neurons, the average half-life of proteins doubles between young and aged mice—4 and 24 months old, respectively—and increases from middle age onward, the study found. Many of those destruction-resistant proteins are involved in synaptic function, suggesting that synapses may be especially vulnerable to declining protein turnover.

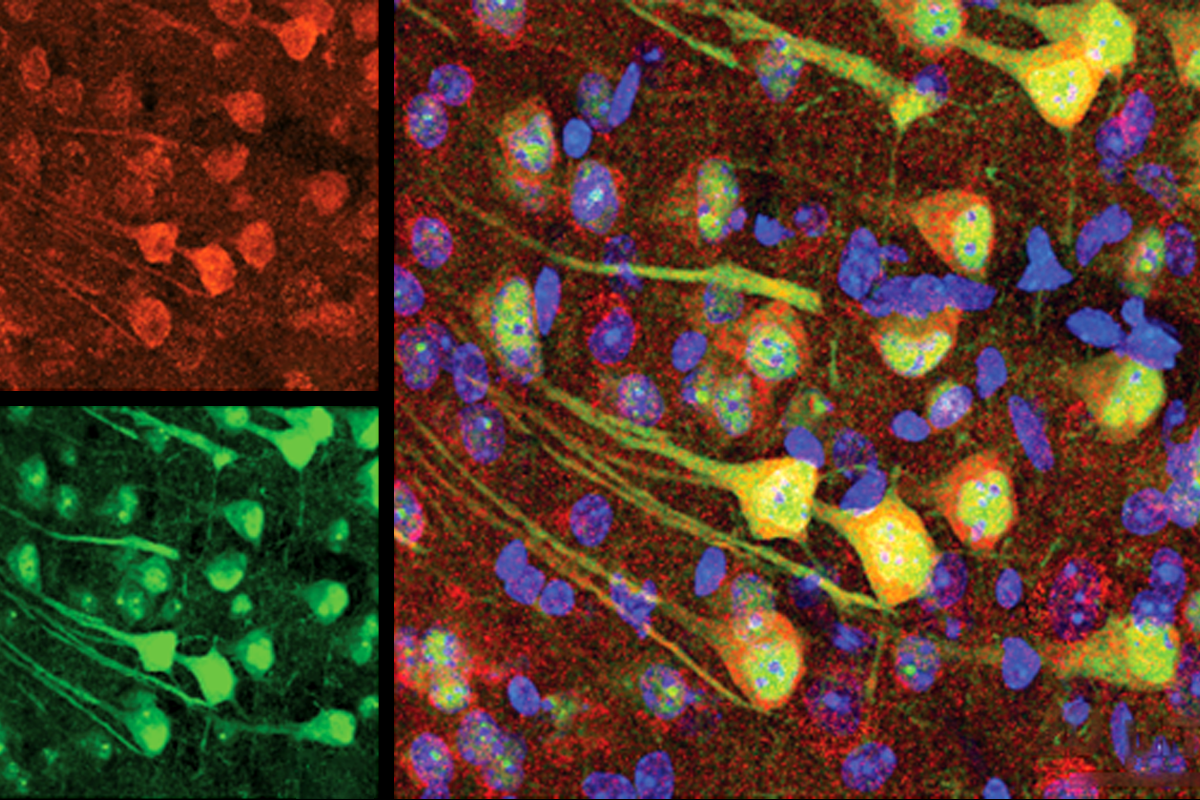

Because protein aggregation also rises with age—and those clumps are thought to clog the degradation machinery—Guldner and his colleagues isolated tagged protein aggregates to identify all of their protein components. Of the 1,726 proteins that make up the neuronal “aggregome,” about half show age-related increases in longevity, including many synaptic proteins.

And some of those proteins show up in microglia, the study also found, especially those from aged mice. Of the 1,027 proteins enriched in microglia from aged rodents, 390 were prone to aggregation and 326 were resistant to degradation. A total of 166 cropped up in all three protein sets.

T

It is unclear, however, if neurons create more waste with age or if microglia are worse at dealing with it, Mayor says. “I think this is the next series of questions to answer.”

Both scenarios likely occur simultaneously and compound each other, Guldner says. “Our hypothesis is that this is probably a protective mechanism. Neurons are basically trying to save themselves by releasing this waste,” he says.

But what starts out as a protective mechanism could backfire as microglia face their own age-related stress. Instead of tidying up, older microglia begin to hoard dysfunctional proteins while continuing to consume overburdened synapses. That process could contribute to the spreading of protein aggregates—a hallmark of neurodegenerative disease—and age-related synapse loss, Guldner says.

Some synaptic components persist for more than one month, so two-weeks of protein tracking in the new work may not have captured all neuronal proteins, says Jeffrey Savas, associate professor of neurology, pharmacology and medicine at Northwestern University, who was not involved in the study.

Still, “at the end of the day, protein half-life is an estimation,” Guldner says. And if the labeling window is half the length of the average protein’s lifespan, “you should be able to make fairly accurate conclusions.”

A possible next step is to investigate whether the changes observed in aged mice are accelerated in Alzheimer’s disease models, Guldner says. The group is also interested in how protein turnover varies across brain cell types and tissues, including the cerebellum and white matter. Microglia within those regions are particularly sensitive to aging, according to previous studies from the lab.

Such experiments would require more sensitive equipment, or pooling animals to reach detectable protein levels, Guldner says. “These are ambitious efforts.”

Recommended reading

Aging as adaptation: Learning the brain’s recipe for resilience

Age-related brain changes in mice strike hypothalamus ‘hot spot’

Two primate centers drop ‘primate’ from their name

Explore more from The Transmitter

Protein tug-of-war controls pace of synaptic development, sets human brains apart

Aging as adaptation: Learning the brain’s recipe for resilience