Bringing African ancestry into cellular neuroscience

Two independent teams in Africa are developing stem cell lines and organoids from local populations to explore neurodevelopmental and neurodegenerative conditions.

Humans first emerged in Africa, but neuroscience research is largely skewed toward people of European ancestry. Most large genome-wide association studies of schizophrenia, autism, depression, Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, each enrolling hundreds of thousands to millions of people, have no participants of African ancestry, a 2020 paper found. And stem cells have a similar diversity problem; about 67 percent of lines come from donors of European ancestry, according to a 2022 study.

“There’s a big gap in terms of the stem cell lines that have been made from humans and our genetic origins,” says Mubeen Goolam, senior lecturer in human biology at the University of Cape Town.

Goolam and others are working to change that by developing stem cell lines and organoids from African donors. Their hope is to ensure that an entire continent doesn’t lose out on the benefits of advanced neuroscience research.

At the same time, research rooted in Africa could uncover information—such as protective gene variants—that benefit the global population.

“Individuals of African ancestry are the most genetically diverse people on the planet,” says Daniel Weinberger, who directs the Lieber Institute for Brain Development, where he launched the African Ancestry Neuroscience Research Initiative in 2019.

More than 3 million new variants were identified in the genomes of 426 African participants from 50 ethnolinguistic groups in a 2020 study by the Human Heredity and Health in Africa consortium; another 1,950 groups are yet to be sampled. Including people of African ancestry in research “will have implications for understanding illness across all populations,” Weinberger says.

N

Once he and his team have created the models, Goolam says, they hope to attract funding for their next steps, which include provoking neural tube defects, studying their progression and testing folic acid or other potential treatments. The team also plans to model hydrocephalus, another developmental condition that disproportionately affects African children.

“There are a whole lot of neurological diseases and disorders that occur more commonly in Africa than they do in other parts of the world,” he says. Given the dominance of the Global North in shaping the research agenda, these conditions are seldom prioritized.

That means if African scientists don’t launch these kinds of projects, no one will, he says. “Interest has to be driven by people who want that work to happen.”

A

“It’s now well established that the more African you are, the more APOE-4 is not a risk,” says Mahmoud Maina, a Wellcome Trust-funded neuroscientist and founder of the Biomedical Science Research and Training Centre in Yobe State, in northern Nigeria.

Still, APOE-4 is used as a therapeutic target and to recruit participants for clinical trials, Maina says, so future treatments based on it may have limited relevance for people of African ancestry.

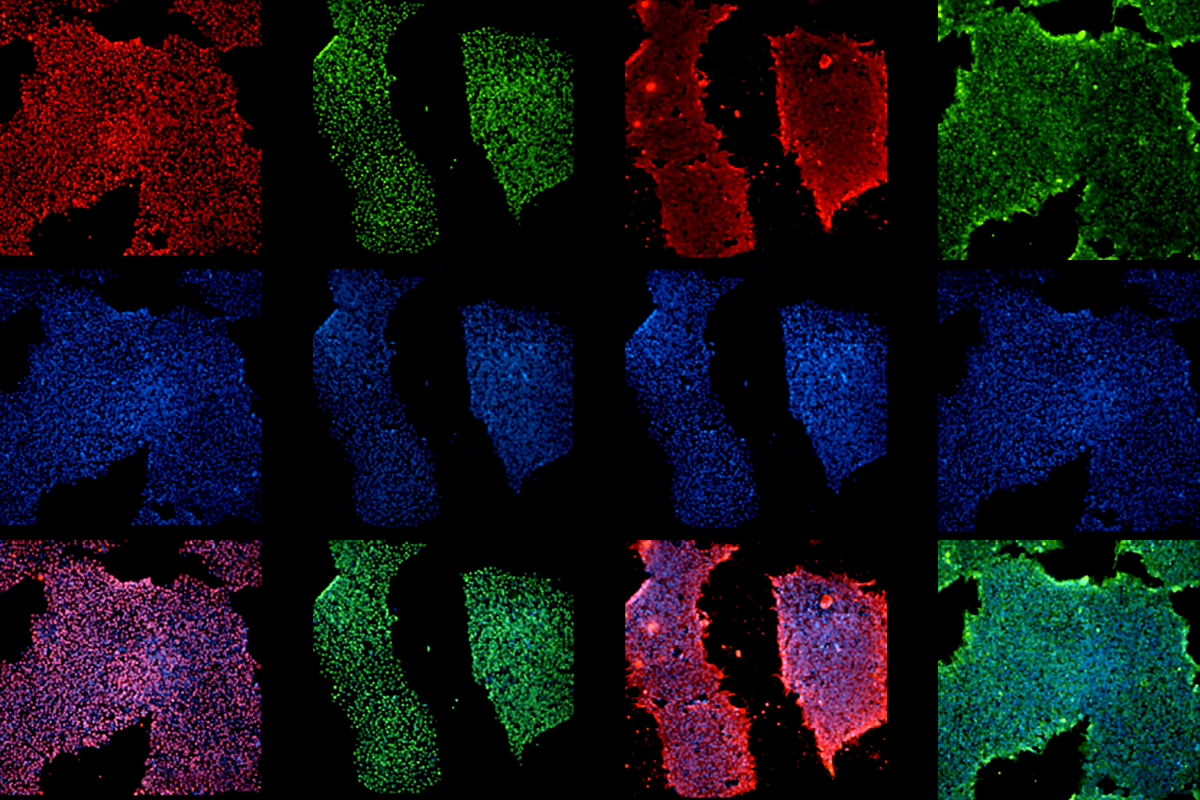

To help identify novel mechanisms, Maina and his colleagues have launched the African iPSC Initiative. Donating postmortem brain tissue, which is crucial for Alzheimer’s research, is often culturally taboo in Africa, Maina says. But iPSCs, or induced pluripotent stem cells, are easier to accept, and it helps that Maina has been doing outreach locally for more than a decade and has a special status as a Shettima Ilmube, or “custodian of knowledge,” in his local community.

So far, the team has established 11 iPSC lines from local donors without Alzheimer’s disease, representing five ethnic groups in the region. One of the initiative’s projects involves introducing genetic variants associated with frontotemporal dementia or Alzheimer’s disease into the lines to study disease mechanisms in an African genetic background.

Maina and his colleagues are also registering a cohort of people with Alzheimer’s from six local hospitals whom they plan to follow over time, using whole-genome sequencing, comprehensive neuropsychological diagnoses and iPSCs to study how disease severity and progression is related to genetic and other risk factors. In August, they collected 1,200 blood samples and about 1,000 skin biopsies from adults aged 60 years and older from local communities; these can be developed into iPSC lines for a cohort that the researchers will follow and screen for Alzheimer’s as they age.

The team plans to share all lines with international cell banks. After all, most of what we know about African genetics comes from African Americans, which means that knowledge is biased toward regions that were involved in the slave trade, Maina says. Northern Nigerians, for example, unlike their southern neighbors on the Gulf of Guinea, are underrepresented in those datasets. “It could be that in our populations, we can find something that can tell us something entirely different,” he says.

Alzheimer’s research conducted in another Global South country, Colombia, found Aliria Rosa Piedrahita de Villegas, who, despite belonging to a family group that genetically disposed her to develop Alzheimer’s disease in her 40s, didn’t show signs of cognitive decline until her early 70s, protected by a rare variant in APOE that is now being explored for treatment possibilities.

“That’s the value of studying differential effects in different ancestral groups,” Weinberger says.

In search of such protective mutations, the African iPSC Initiative is collecting cells from centenarians. “We [may] have a lot of Aliria Rosas sitting down in villages,” Maina says.

S

The research didn’t receive much attention at the time, Loring says, and the project’s funding dried up. But now, more than a decade later, Loring plans to develop the lines into organoids through a company founded with two of her former postdocs.

As for Maina’s and Goolam’s new initiatives, Loring says she is “delighted.”

She published a paper in June calling for the establishment of ethnically diverse iPSC reference lines that better represent the world population. “There’s so many things you could do with these cells,” she says.

Given Africa’s enormous diversity, Maina and Goolam know that genetic representation is still an issue. “Because I’m in South Africa with my colleagues, we’re making lines from South Africans, and [Maina] is a Nigerian making lines from Nigerians,” Goolam says. But by developing a proof of concept in one region, he says, “if you gain enough traction and funding to expand things, then you can make little nodes of this kind of work around Africa.”

On a continent where national budgets are slim, and science funding from the Global North tends to be earmarked for infectious disease research, it can be difficult to make a case for funding less critical topics, Goolam says. But he argues that investing in neuroscience and stem cells there could build knowledge and specialization comparable to what Africa has achieved in infectious disease: “You will grow local expertise in those fields.”

Recommended reading

Addressing the lack of infrastructure and training that stymies African neuroscience

First Pan-African neuroscience journal gets ready to launch

Sharing Africa’s brain data: Q&A with Amadi Ihunwo

Explore more from The Transmitter

Organoids and assembloids offer a new window into human brain

Everything, everywhere, all at once: Inside the chaos of Alzheimer’s disease