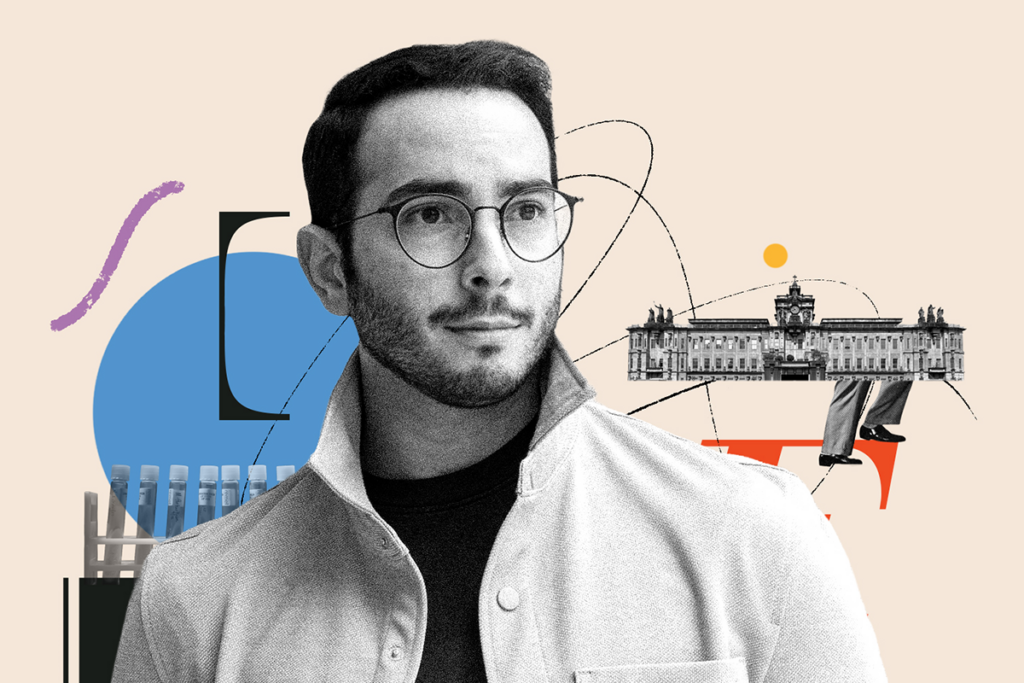

Frameshift: Raphe Bernier followed his heart out of academia, then made his way back again

After a clinical research career, an interlude at Apple and four months in early retirement, Raphe Bernier found joy in teaching.

Raphe Bernier became a researcher to help people, but every advancement in his career moved him farther from the patients he cared about. After nearly two decades in academia, he left his position as a full professor and endowed chair at the University of Washington for a job at Apple, where he spent several years creating and testing tools to support mental health. Now he’s back at UW teaching psychology to tomorrow’s scientists and clinicians. He spoke with The Transmitter about following his heart and finding his way back to the science he loves.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: How did the nature of your work evolve during your time in academia?

Raphe Bernier: When I started out at UW, it was awesome. I got to work in the lab and be super hands-on with study participants and their families. I loved it. But as time went on, I spent more and more time writing grants and reading and revising my team’s papers. Eventually, I was running the Seattle Children’s Autism Center, which serves between 3,000 and 4,000 patients a year. I spent most days wearing a tie and talking to potential donors, trying to get money so I could keep everything running, or sitting in a room by myself writing grants. I felt so removed from the stuff I loved. I wanted to figure out how to become an assistant professor again or try something new somewhere else.

TT: How did Apple enter the picture?

RB: In 2019, someone from Apple approached me. I knew them through the Autism Center and I didn’t realize they were approaching me for a job; I thought they just wanted to pick my brain about ways technology could be helpful in the field of psychiatry. I said, “I don’t know anything about technology, but here are my thoughts,” and threw out some ideas. Then they invited me down to Cupertino to give a talk. Again, I didn’t think anything of it because I was used to going places to give talks. Then, after that, they said, “We’d like to offer you a job.” And I was like, “Wait, what?”

TT: What was your role at Apple?

RB: I was a clinical scientist on the health products team, in the children and mental health space. I kind of saw myself as an internal consultant. Sometimes the engineers would figure out how to do something with the technology and then ask me if there was a use for it. I would help them explore what was possible. Sometimes I’d say, “That’s bonkers”; other times I’d say, “That’s super cool. Here’s what we could do and how we could test it.” I would design the studies, write the ethics protocols, and if the study involved interviews, I would do some. I was suddenly back doing the stuff I loved doing as a grad student, but being well compensated.

TT: How did it compare with academia?

RB: The people who work at Apple are just brilliant. The way they think about things is incredible. It’s different from the way I think about things, but it’s amazing. And so many of my skills from academia transferred. You have to be able to efficiently explore and evaluate the current research literature, formulate and pitch ideas, and conduct research—everything from designing studies to recruiting participants, analyzing data and sharing findings. Basically, I applied all my expertise and experience from clinical research to product development.

But Apple CEO Tim Cook called all the shots. I used to call all the shots in my own research, and now I was calling zero shots. Sometimes we’d have projects that were super cool and pretty far along in terms of development and we’d put them on the shelf because they “didn’t fit the ecosystem.” The culture was great, though. If I’m going to work for a company, I want to make sure the company’s values align with mine. And our whole job on the health team was to figure out ways to use technology to improve lives.

TT: So what got you thinking about leaving?

RB: I really wanted to help build something that could help people, and we did. We built a screening tool for depression and anxiety that millions of people have on their phones, and I feel really good about that. We would get letters—we called them “Dear Tim” letters—in which people would say their watch saved their life, or the screening tool changed their life, and Tim would share these with us. They were so inspiring, but they were few and far between, and I felt pretty far removed from the impact I wanted to make.

Also, my daughter was in her senior year in high school, and I wanted to spend more time with her and go to all her cross-country meets. Even though I had a pretty flexible schedule at Apple, I wanted to fully control my schedule. I would have stayed at Apple had I been able to work part-time, but that’s not how Apple rolls. My salary at Apple was very generous, so I decided to retire so I could spend more time with my kids. But then a buddy of mine at UW called and said, “Raphe, for years you’ve talked about teaching and how much you love it. Can we get you to teach a class or two?” That’s what brought me back in.

TT: So you didn’t retire after all?

RB: I think I retired for about four months.

TT: And how do you like teaching?

RB: I love teaching with all my heart, and it’s all I’m doing now. I have no administrative responsibilities, no research responsibilities. I just teach, which is actually why I went to graduate school. I teach research methods and psychopathology. In the spring, I’m teaching a new course on artificial intelligence and psychology. I’m excited to figure out what I’m going to do for that. I love what I get to do each day. I will do this until they roll me out of the building.

TT: What do your colleagues in research think about your moves?

RB: When I was at Apple, I don’t know how many of them said, “Dear God, Raphe, get me a job there.” And there were also some who said, in a good-natured way, “Oh, you sold out.” But I worked so hard in academia—so many long hours, and I was always stressed. I was pretty burnt out in 2019. And I feel like the world was looking out for me, because I don’t think I could have managed running a huge autism center when COVID happened. I just didn’t have the emotional energy for it. When I went to Apple, I had no stress and was paid a billion times more than I got as a professor.

I did get teased a little bit from some of my research friends when I moved to teaching. They were like, “What are you doing? Why do you want to do that?” But I love it, and we need teachers who love it.

TT: What advice do you have for folks who feel like their career has moved away from what they once wanted?

RB: The first thing I would say is ignore the idea that you’re somehow failing by choosing to try something new. I had that idea in the back of my head, that industry is where you go when you can’t hack it in academics. And that’s why I felt like I had to do everything—get the endowed chair, my own building, all the grants—before I could try something else. The second thing I would say is you can always go back to being an academic. There’s this notion that once you leave, you can’t do it again. But there are plenty of us who have done it. And the third thing I want to say is you’re going to find super awesome, exciting people wherever you go—so embrace that.

Recommended reading

Securing the academic pipeline amid uncertain U.S. funding climate

Frameshift: At a biotech firm, Ubadah Sabbagh embraces the expansive world outside academia

Tracing neuroscience’s family tree to track its growth

Explore more from The Transmitter

Frameshift: Shari Wiseman reflects on her pivot from science to publishing

‘How to Change a Memory: One Neuroscientist’s Quest to Alter the Past,’ an excerpt