Neuro’s ark: How goats can model neurodegeneration

Since debunking an urban legend that headbutting animals don’t damage their brain, Nicole Ackermans has been investigating how the behavior correlates with neurodegeneration.

An urban legend permeates the scientific literature: Animals that frequently butt their head do so without sustaining any brain damage.

Intrigued by this bit of trivia, Nicole Ackermans decided to spend her postdoctoral fellowship investigating how the skull anatomy of headbutting animals shields their brain from damage. She examined the brains of four bighorn sheep and three muskoxen, publishing her findings in 2022.

“Long story short, we found brain damage,” says Ackermans, assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Alabama.

Phosphorylated tau, a protein marker of neurodegeneration, clumped at the bottom of the animals’ brain folds and around blood vessels—the same pattern that occurs in athletes, military personnel and other people diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy. “And actually, evolutionarily, it doesn’t really make sense to not get brain damage, because why would you have a headbutting competition where nobody loses? There has to be somewhat of a downside,” Ackermans says.

Now Ackermans studies goats and other animals with extreme head-hitting behavior as a model of brain injury and neurodegeneration in people.

Ackermans spoke with The Transmitter about what she is currently working on, what nontraditional models can offer neurodegeneration research and how to coax goats into headbutting.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Transmitter: What makes goats a good model for studying neurodegeneration?

Nicole Ackermans: Goats self-inflict their own brain injuries. They headbutt each other and things in their environment. So it’s a lot more realistic than a weight drop model with a mouse, where you anesthetize them, drop a weight on their head to create a brain injury, and then keep them under anesthesia and monitor them. Goats’ brains are closer in size to humans’, and they have folds. So we suspect the forces distributed would be a little bit more representative of real life.

The main question is how often and how hard you have to hit your head to get brain damage and to get chronic disease—we don’t know the answer.

TT: How are you tackling that question?

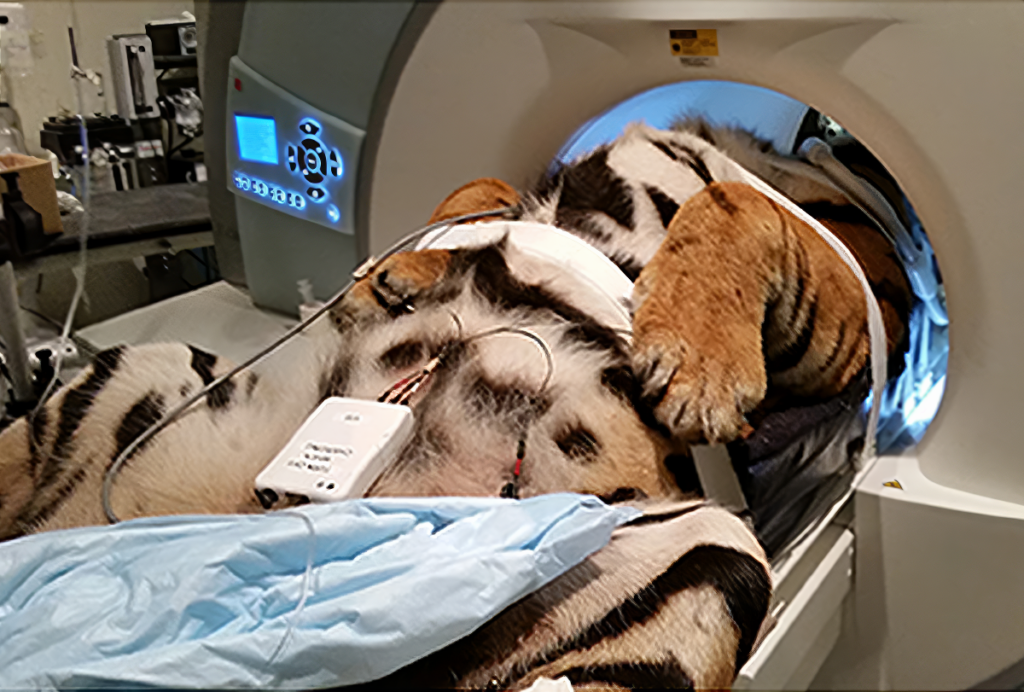

NA: I’m trying to basically take everything you would use to diagnose a human with traumatic brain injury or chronic traumatic encephalopathy and apply it to our models. We did a six-month pilot study of three goats, in collaboration with Mississippi State University, a vet school about an hour away. They have barns and everything that we need. They take care of the animals, and we just let the goats perform their natural behavior, which is apparently headbutting all day long. I was like, “We’re going to pretend that they’re patients.” We did blood draws, spinal taps, PET-MRI scans and behavioral tests, and at the end, we collected brain samples and did immunohistochemistry as well.

At the beginning of the experiment, they didn’t headbutt, and I was really worried that they never would. It’s not something you think about: How do you make goats headbutt? I talked to some farmers, and they told me you have to give them something to compete over. So we got them a little bridge to climb, and then they would fight over who got to stand on top of it.

The results are not published yet, but it’s looking like even at 1 year old, they already show signs of brain damage, including phosphorylated tau and neuroinflammation. We have six months’ worth of videos of these goats; we want to count every single headbutt and correlate how many headbutts equal how much brain damage. Overall, it seems that they each headbutted about 20,000 times, which is way more than we expected.

TT: How does that number compare with the hits an athlete takes?

NA: The goats hit more frequently but at lower forces. I believe this still makes them comparable to humans. Evidence is emerging that shows repetitive mild impact is also a large contributor to neurodegeneration, although much more work needs to be done to find out exactly which forces and how many hits.

TT: What scientific tools are on your wish list?

NA: It’s hard to use a lot of the big, fancy equipment on our organisms, because it is really attuned to humans and mice and is not going to work on, quote, unquote, “weird species.” We get a lot of background with our fluorescence. A lot of the automatic counting or staining methods don’t work.

More money for more goats is really what I want. I have plans for a five-year, 40-goat experiment that I submitted to the National Institutes of Health. But the way that funding is going right now, I don’t know when that’s going to happen. I really want to look at sex and age differences. It’s really hard to get old goats because nobody keeps them on their farm when they’re old; it’s kind of a waste for agricultural systems. So we would have to age our own goats.

TT: What would you like other neuroscientists to know about this model?

NA: Some of the more traditional neuroscientists think this work is silly. I’m not trying to convince them that goats are better than mice, because I’d rather stick with my own work. I just want people to know that there’s potential here. One of the reasons that we are stuck and haven’t found a cure for Alzheimer’s disease is because of mice. There’s only so much that you can translate from mice. But by being a little bit more open-minded with these different animals and looking at how they survive in nature, hopefully we can get new ideas about where to direct our search for therapies.

Recommended reading

The non-model organism “renaissance” has arrived

Everything, everywhere, all at once: Inside the chaos of Alzheimer’s disease

Explore more from The Transmitter

Home makeover helps rats better express themselves: Q&A with Raven Hickson and Peter Kind

Diving in with Nachum Ulanovsky