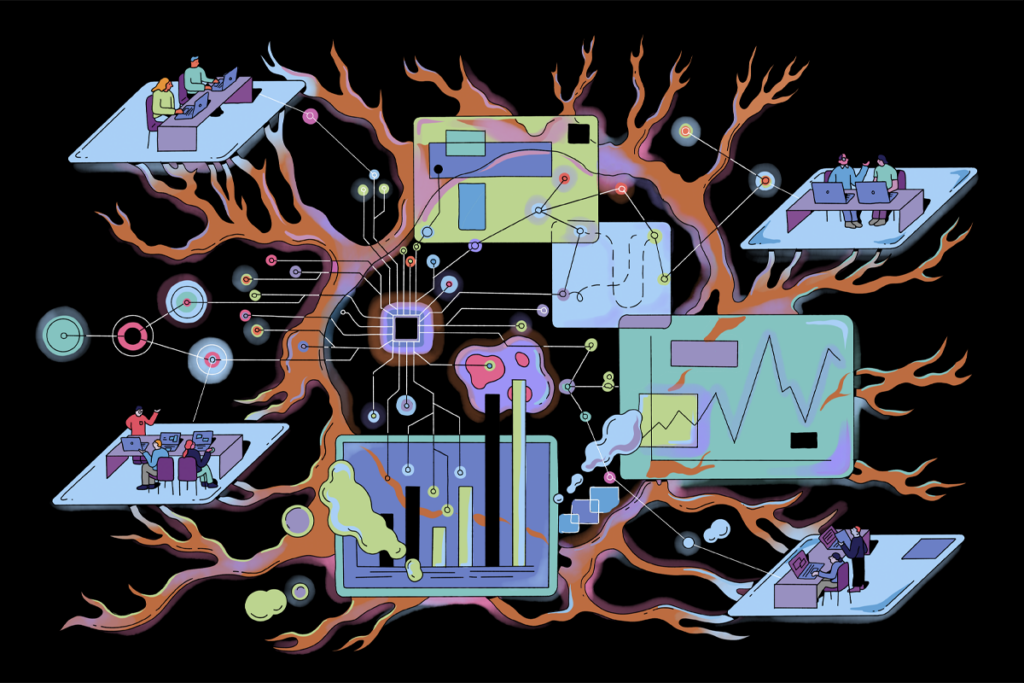

Neuroscientists study brain computation using the traditional academic model—individual laboratories leading independent research programs—that has worked so well in other fields. This system has delivered incredible insights: breakthroughs in synaptic learning, revelations about how the cortex encodes visual scenes, and more. It has been broad, detailed in places, and remarkably productive.

Despite these successes, the task ahead remains daunting. To achieve a deeper understanding of how the brain functions as a whole, these isolated pieces of knowledge must be assembled, piece by piece. And as a field, we struggle to integrate knowledge, facilitate data-sharing and validate insights across laboratories. These challenges seem almost inherent to the system, rooted in our recruitment practices, individual incentive structures and even our funding mechanisms. The brain demands integration, yet our system incentivizes fragmentation.

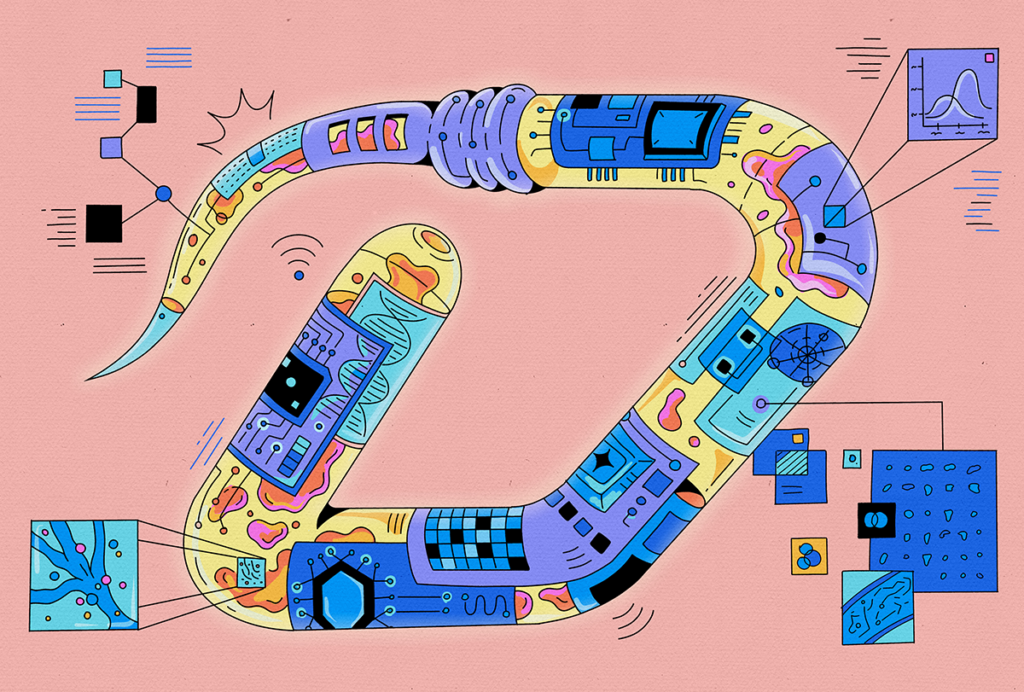

Recognizing these challenges, Christof Koch, myself and many colleagues at the Allen Institute created OpenScope, a platform for shared, high-throughput neurophysiology experimentation. Modeled after large-scale observatories in fields such as astronomy and physics, OpenScope conducts new experimental projects proposed by scientists around the world. In those projects, we record from thousands of neurons across the mouse brain, using either multi-probe Neuropixels recordings or multi-area two-photon calcium imaging. The resulting datasets are then shared with the selected research teams, who carry out their proposed data analyses, and subsequently made available to the broader community.

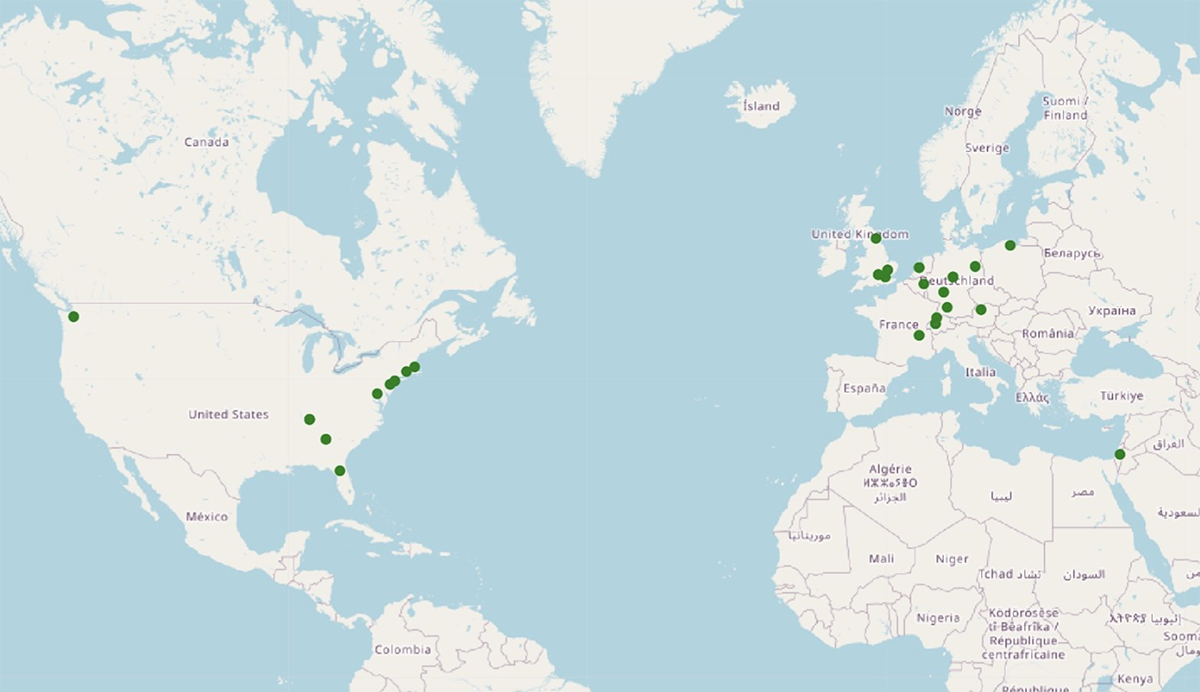

Initially, OpenScope focused on executing independent projects selected through a double-blind review process to ensure neutrality and alignment with the field’s evolving interests. After several cycles, however, a clear opportunity emerged: Many proposals converged on questions related to predictive processing. With guidance from our steering committee—Adrienne Fairhall, Satrajit Ghosh, Mackenzie Mathis, Konrad Körding, Joel Zylberberg and Nick Steinmetz—and support from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, we decided to unite multiple laboratories around a single, community-defined experiment. The idea was to commit OpenScope’s resources to a collaboratively designed project to help to unify the disparate theories and data that have emerged from experiments on predictive processing.

O

ur first step was to submit a proposal for a workshop on predictive processing at the 2024 Cognitive Computational Neuroscience conference in Boston, together with Körding, Colleen Gillon and Michael Berry. In preparing for the event, we realized organizing a discussion during a workshop would not be enough to design an actual experiment. So, months before the conference, we created a shared Google Doc to begin shaping the conversation, conducting a deep review of the predictive processing literature and dedicating hours each day to reading, summarizing and synthesizing.