Psychedelics research in rodents has a behavior problem

Simple behavioral assays—originally validated as drug-screening tools—fall short in studies that aim to unpack the psychedelic mechanism of action, so some behavioral neuroscientists are developing more nuanced tasks.

For the past two and a half years, a team of five labs in the San Francisco Bay Area have endeavored to nail down how psilocybin affects the way mice behave.

Psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs have been shown to improve anxiety and depression symptoms in people, but results in mouse studies are less consistent. Those inconsistencies spell trouble for researchers trying to unpack the drug’s mechanism, because if behavioral changes in mice don’t mirror those in humans, the underlying biological changes might be irrelevant, says team member Boris Heifets, associate professor of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine at Stanford University.

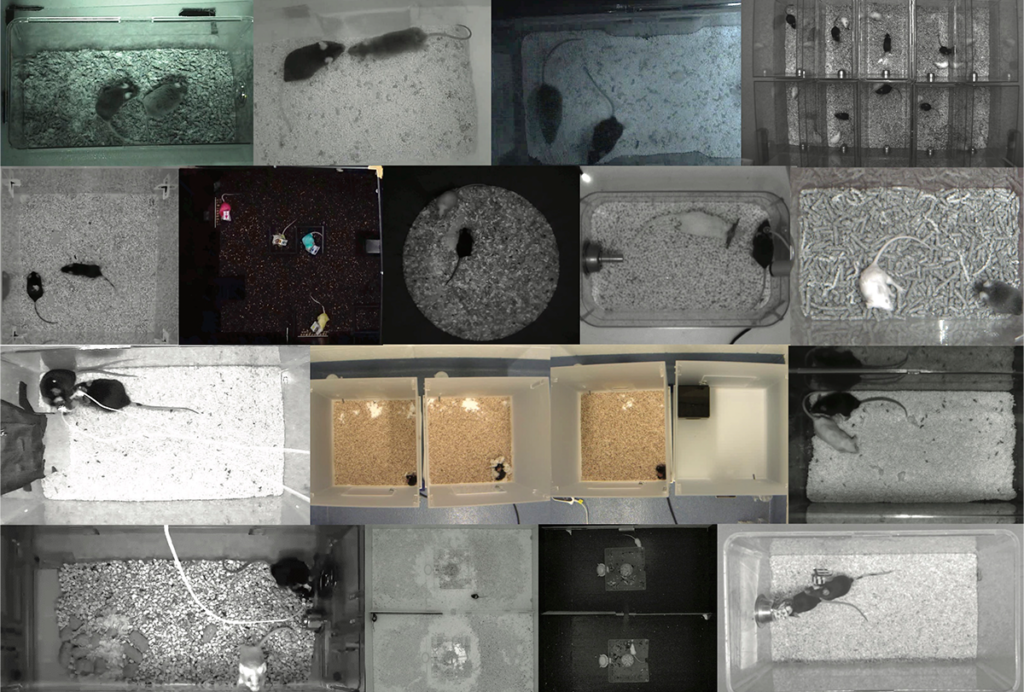

So, to establish a behavioral ground truth, the five labs gave about 200 mice the same dose of psilocybin and measured how the drug affected the animals’ performance on a range of simple behavioral assays, including the elevated plus maze and open field, tail suspension and forced swim tests, while taking the drug as well as 24 hours later.

While on psilocybin, the mice showed a temporary increase in anxiety-like behaviors, including spending less time than usual exploring new objects and open areas, the team reported in April. But, unlike in people, the drug had no lasting effects once it wore off.

“We were a little dismayed to find very little to go on,” Heifets says.

The issue, some behavioral neuroscientists argue, is not replication between labs—it’s the assays themselves.

“I love the idea of these multisite experiments in animal models, but the models—the behavioral models—still have to be the right ones,” says Jennifer Mitchell, professor of neurology and psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, San Francisco. “The tests themselves—I’m not sure how much they tell us about what a psychedelic is actually doing.”

Some scientists are working to outgrow the field’s behavior problem. Instead of identifying a simple test that produces a universal result, they are designing more sophisticated tasks that more accurately reflect human behavior. Their results are beginning to tease apart the circuits underlying negative affective states and hallucinations, and they hope those observations will translate to insight into how psychedelics work—and how they can be improved.

“I believe to find new treatments, we need this mechanistic understanding that we can only gain from using more theory-driven behaviors,” says Katharina Schmack, group leader at the Francis Crick Institute.

P

For example, the forced swim test, created in 1977, involves placing a rodent in a water tank and timing how long it takes the animal to stop trying to swim or escape, a state coined “behavioral despair.” Doses of monoamine reuptake inhibitors reduced the time an animal spent immobile, whereas other drug classes had no effect.

The test detected “stress-induced states that were reversed by SSRIs” and proved a useful tool for pharmaceutical companies to reduce the drugs’ side effects without losing their efficacy, says Adam Kepecs, professor of neuroscience and psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Where the problem has potentially emerged,” Robinson says, was when researchers began using the forced swim test as a more general model of depression in experiments designed to figure out the underlying biology of the disorder or the mechanism of action for new types of depression treatments—such as psychedelics. “We don’t know if the mechanism that drives this change in immobility behavior is the same as the mechanism that’s important in treating depression.”

One reason it’s difficult to use the forced swim test and other simple assays to study mechanisms of action is that they are a “one-shot deal,” says Rosemary Bagot, associate professor of behavioral neuroscience at McGill University. Novelty plays a role in how animals behave in assays such as the open field test, in which researchers measure how much time an animal spends against the walls of an enclosure versus in the middle, which means animals cannot be tested repeatedly.

In addition, the standard assays are too blunt to detect nuanced changes, yet sensitive to small experimental differences—such as the identity of the researcher handling the animal, the temperature and lighting of the room, and the animal’s overall stress level—that can affect how the animal behaves, Bagot says.

Tasks that involve training an animal to perform a more complex behavior, however, “are perhaps more sensitive to detect subtle differences,” Bagot says. And they generate much more data. “You’re getting data that you can do interesting analysis with,” she says, “where you can abstract out these underlying processes that might be influencing behavior.”

R

Robinson’s approach has been to develop a task related to an objective measure of depression in people—negative affective bias, or a tendency to interpret experiences in a negative light—and test how a dose of a psychedelic modifies that behavior, “rather than taking a subjective, self-reported symptom in a human that I can never ask a rat to tell me if it has that,” Robinson says.

In the task, rats dig through two bowls, each filled with a different material but only one containing a food reward; rats are “brilliant at” the task and learn which material has food in it within one session, Robinson says. The animals repeat the task with different stimuli under a positive, negative or neutral affective state and then choose which food-related material they prefer. “If they favor one over the other, then we know that that’s because there was an affective state change at the time that they learned it,” Robinson says.

The rats preferred a neutral digging material over one associated with a negative experience—an injection of a benzodiazepine inverse agonist or the stress hormone corticosterone—Robinson and her team reported in 2024. A dose of ketamine or psilocybin delivered an hour before the test removed this preference, and a dose delivered 24 hours before the test resulted in the animals preferring the previously negative-coded material over the neutral one.

“The negatives become positive. So there’s been this relearning effect,” Robinson says. Robinson is still validating the assay, but in future work her group plans to tease apart the underlying circuit by inhibiting different brain regions and seeing how it affects the rats’ preference, she says.

Kepecs and his team, including Schmack when she was a postdoctoral researcher in his lab, have taken a computational psychiatry approach to study hallucinations in mice; the work is meant to be a model of psychosis, but the underlying principles can apply to studies of psychedelic mechanisms, he says. In this assay, mice stick their head in a port and listen for a tone that is played at unpredictable times amidst background noise. They poke their nose in one port if they hear it and in another if they do not hear it. They receive a water reward for correct answers, but the treat comes at different times—so Kepecs and his team can measure how confident the animal is in its answer by how long it waits for a reward. This enabled the researchers to rule out mistakes—the animal does not wait long—from moments when no tone played but the mouse demonstrates confidence that it heard one—in other words, a hallucination.

Increased dopamine signaling in two parts of the striatum before the stimulus played correlated with a hallucination. Both administering ketamine and boosting dopamine signaling using optogenetics increased hallucination events without affecting overall decision-making, whereas haloperidol, an antipsychotic drug that blocks D2 dopamine receptors, prevented them.”

This type of task provides “many trials to compare against, to isolate a moment,” as opposed to the simpler assays that only provide information on a session-by-session basis, Kepecs says. And once you isolate a moment, you can begin to probe the mechanism driving it. This approach is common in systems neuroscience labs focused on broader questions about brain function but is relatively rare in labs dedicated to basic psychiatric science, Kepecs says.

The best way forward for basic psychedelics studies, Kepecs, Robinson and Bagot say, is not to abandon all simple behavioral assays but rather to think about their most appropriate uses and, when more sophisticated research questions are involved, to collaborate with behavior experts to develop more nuanced tasks.

“I think that using well-designed, computationally modelable decision-making tasks can help us to tease out how psychedelics are changing the way the brain processes information,” Bagot says.

Recommended reading

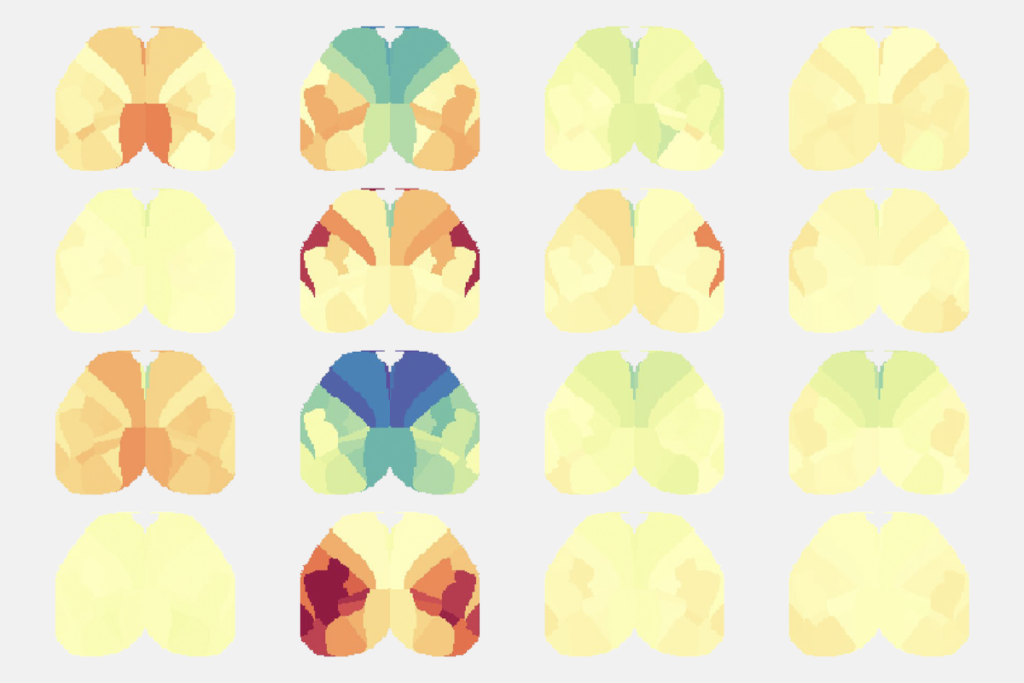

Psilocybin rewires specific mouse cortical networks in lasting ways

Psychedelics muddy fMRI results: Q&A with Adam Bauer and Jonah Padawer-Curry

Why we need basic science to better understand the neurobiology of psychedelics

Explore more from The Transmitter

Competition seeks new algorithms to classify social behavior in animals