Adults with autism may have high burden of health problems

Adults with autism may suffer from various health problems, ranging from psychiatric conditions to motor symptoms that resemble Parkinson’s disease, according to two studies presented Thursday at the 2014 International Meeting for Autism Research in Atlanta.

Aging in autism: Men over 50 with autism look old for their age and may move particularly slowly, with a rigid gait.

Adults with autism may suffer from various health problems, ranging from psychiatric conditions to motor symptoms that resemble Parkinson’s disease, according to two studies presented Thursday at the 2014 International Meeting for Autism Research in Atlanta.

Some of the conditions may stem from people with autism feeling like outsiders in society, says Lisa Croen, director of the Autism Research Program at Kaiser Permanente, an integrated healthcare delivery system in California. Croen led one of the studies, which documents the health status of more than 2,000 adults with autism.

“From our experience, inclusion and feeling part of society really does impact on health status,” says Croen. “It’s very important to include adults with autism in all sections of society.”

The findings are also of concern given the rising numbers of children diagnosed with autism, the researchers say. They highlight how little is known about adults with autism, many of whom may be misdiagnosed with other conditions.

“There is almost no literature on older adults with autism in the field, so we have virtually no knowledge base,” says Joseph Piven, professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who presented the second study.

Piven and his colleagues pursued a “boots-on-the-ground approach,” sending queries to nearly 14,000 households and contacting several health agencies in North Carolina. After three years of searching, they found 20 men with autism who were over 50 years old.

“I think the main finding is how hard it was for Joe Piven’s group to find people,” says Catherine Lord, director of the Center for Autism and the Developing Brain at New York-Presbyterian Hospital. Lord has followed children with autism over long periods of time, but was not involved in either new study.

Hidden adults:

Most of the men in Piven’s group have markedly low intelligence quotients: 40 percent have IQs under 35 and about 60 percent have IQs below 50. This is probably because to be diagnosed with autism decades ago — when there was much less awareness about the disorder — they would have had to have severe symptoms, says Piven.

One of the men in the study was among the first group of 11 people to be diagnosed by Leo Kanner in 1943. Some of the others received a diagnosis for the first time during the course of the study and had instead been diagnosed with disorders such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. “One of the big stories here is that there are people out there who are misdiagnosed. We just can’t find them,” Piven says.

A 2012 study found, for example, that about 10 percent of adult patients in a state psychiatric hospital have undiagnosed autism1.

Of the 20 men in Piven’s group, 17 look older than their age, with a stooped posture, and about half have at least one symptom associated with Parkinson’s disease, including tremors, slow movement and rigid gait. About one-quarter of the group has two or more of these symptoms.

One of the men was already undergoing treatment for Parkinson’s disease, and the researchers referred two more for therapy. This is a possible prevalence of 3 in 20, which is much higher than the 1 in 1,000 rate of Parkinson’s in the general population, notes Piven.

“One of the big stories here is that there are people out there who are misdiagnosed. We just can’t find them.”

However, the results are preliminary, he cautions, and may be affected by the men’s medical history. Drugs for epilepsy, which commonly co-occurs with autism, can cause motor deterioration, for example.

Lord notes that many older adults with autism have spent time in institutions, where they might have received strong courses of drugs.

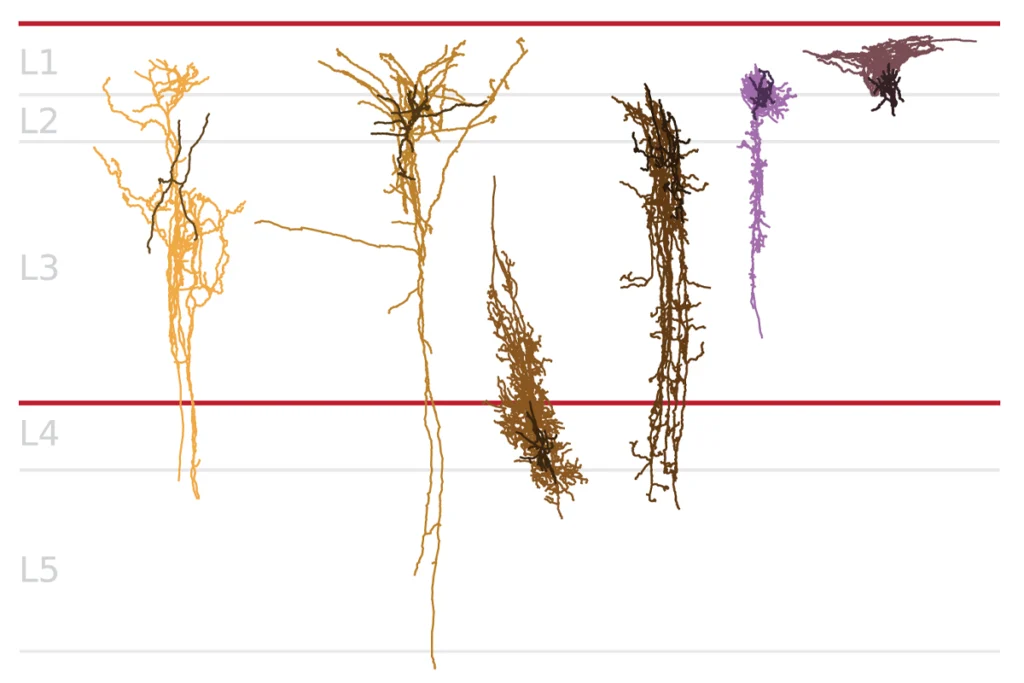

Motor deficits are also a common feature among children with autism, says Stewart Mostofsky, director of the Laboratory for Neurocognitive and Imaging Research at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, who was not involved in the study. Slow movement and rigid gait are more common than tremors, he says.

“It’s certainly possible that at least some of these features were present for many, many years, and possibly even in childhood,” Mostofsky says.

There may also be an underlying genetic overlap between autism and Parkinson’s disease, says Emanuel DiCicco-Bloom, professor of neuroscience at the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School at Rutgers University in New Jersey. A family of chemical messengers called monoamine neurotransmitters, which include serotonin and dopamine, are implicated in both disorders.

Health registry:

Piven and his colleagues are collecting detailed life histories for each of the participants, aiming to understand how the disorder manifests throughout a lifetime. In contrast, Croen’s study began with medical records to find and study a large number of adults with autism. She and her colleagues found 2,108 adults with autism enrolled in Kaiser Permanente.

They compared these adults — about 1,000 of them are over 30, and 300 are over 50 — with ten times as many controls matched for age and sex.

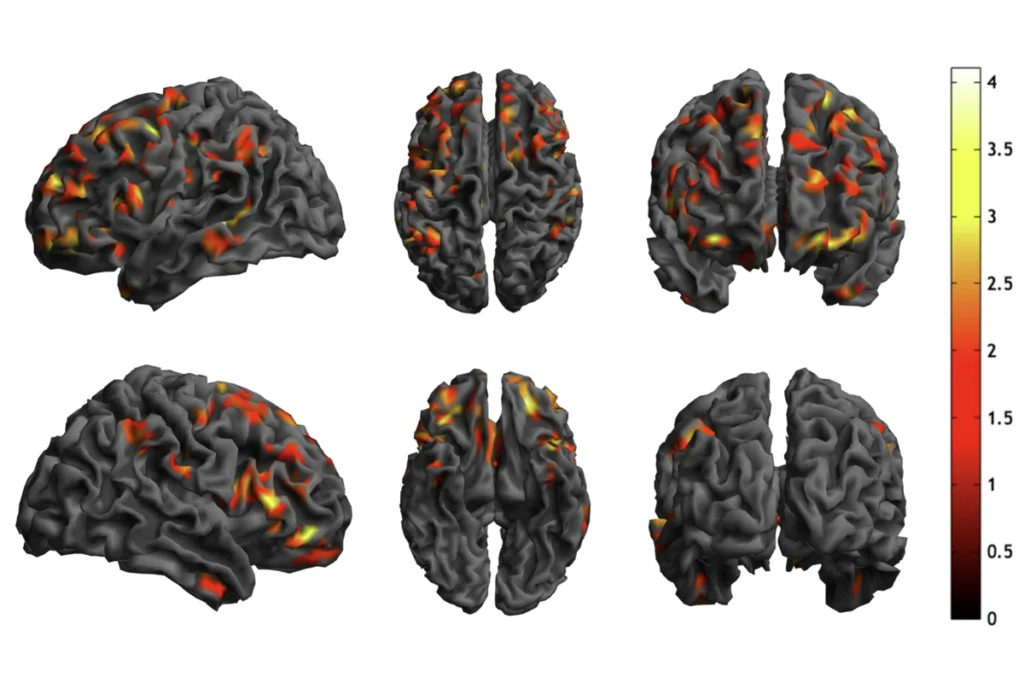

Overall, the adults with autism are more than twice as likely as controls to have depression, anxiety or bipolar disorder, and to attempt suicide, the study found. They are also more likely to have diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders, epilepsy, sleep disorders and high blood pressure.

Interestingly, only the women with autism have a higher chance of having immune disorders than controls do. The rate of cancer is the about the same as in controls, despite the overlap between some autism and cancer genes.

People with autism are also half as likely as controls to use alcohol and to smoke, the researchers found. “The smoking [finding] is quite interesting,” says Lord. This may be because smoking and drinking are social activities and people with autism are less susceptible to peer pressure, she says.

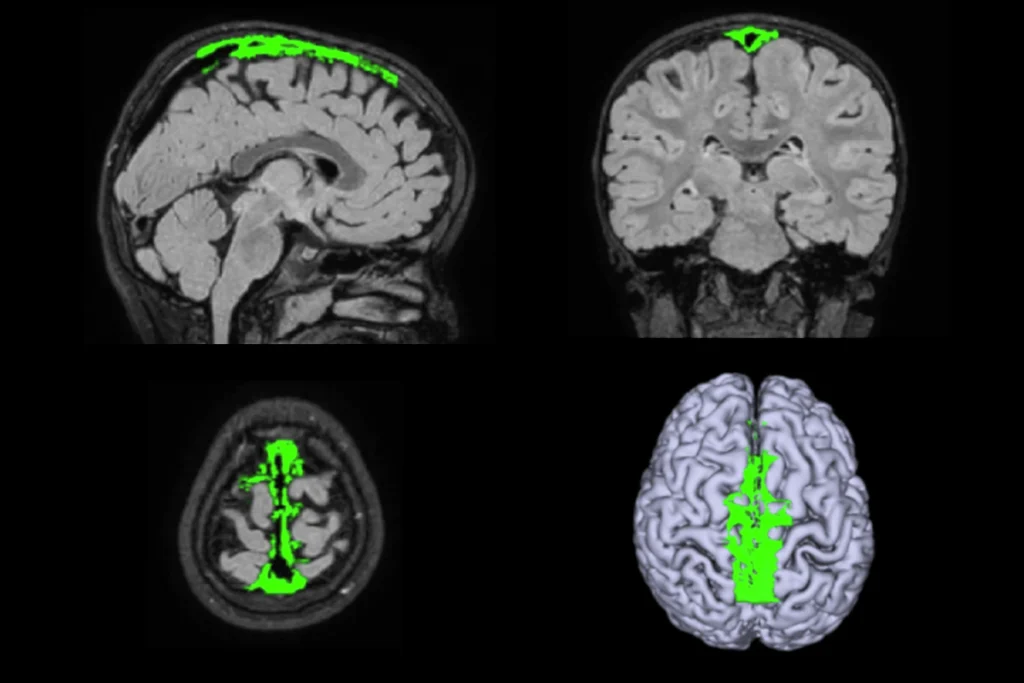

Although health registries are rich with information, Piven warns against relying solely on their diagnosis of autism, which is based on insurance codes. When trying to find adults with autism in North Carolina, his team quickly found 20 people through a health registry — but later discovered that they had a form of dementia that leads to social deficits.

These individuals were diagnosed with autism only after their dementia set in, he says. “I think when you dig into these databases, you’re going to find all this crazy stuff.”

For more reports from the 2014 International Meeting for Autism Research, please click here.

References:

1: Mandell D.S. et al. Autism 16, 557-567 (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

Okur-Chung neurodevelopmental syndrome; excess CSF; autistic girls

New catalog charts familial ties from autism to 90 other conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

Karen Adolph explains how we develop our ability to move through the world

Microglia’s pruning function called into question