Toddlers with autism indifferent to eye contact, study says

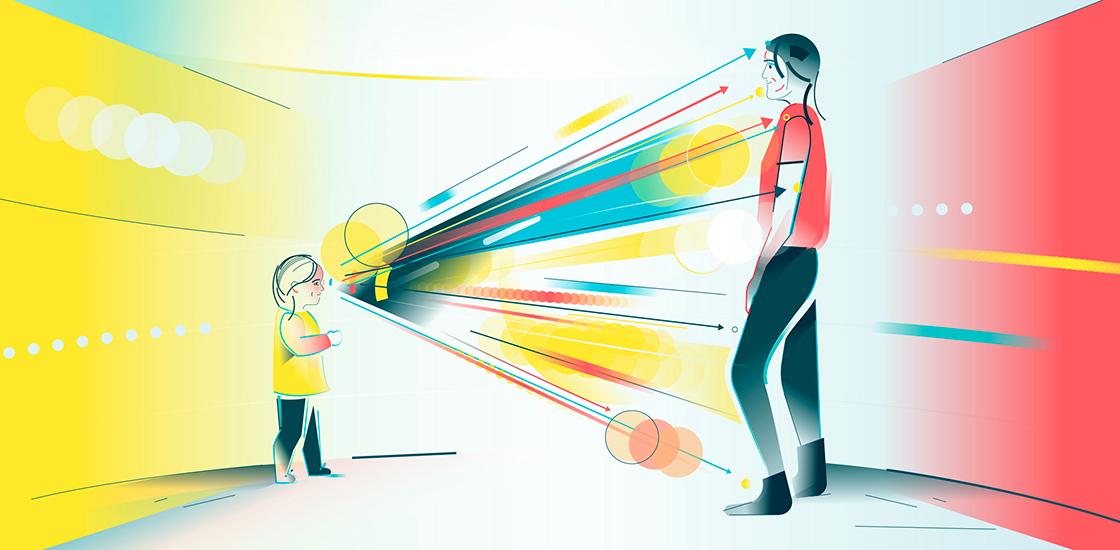

Toddlers with autism are oblivious to the social information in the eyes, but don’t actively avoid meeting another person’s gaze.

Toddlers with autism are oblivious to the social information in the eyes, but don’t actively avoid meeting another person’s gaze, according to a new study1.

The findings support one side of a long-standing debate: Do children with autism tend not to look others in the eye because they are uninterested or because they find eye contact unpleasant?

“This question about why do we see reduced eye contact in autism has been around for a long time,” says study leader Warren Jones, director of research at the Marcus Autism Center in Atlanta, Georgia. “It’s important for how we understand autism, and it’s important for how we treat autism.”

If children with autism dislike making eye contact, treatments could incorporate ways to alleviate the discomfort. But if eye contact is merely unimportant to the children, parents and therapists could help them understand why it is important in typical social interactions.

The work also has implications for whether scientists who study eye contact should focus on social brain regions rather than those involved in fear and anxiety.

Lack of eye contact is among the earliest signs of autism, and its assessment is part of autism screening and diagnostic tools. Yet researchers have long debated the underlying mechanism.

The lack-of-interest hypothesis is consistent with the social motivation theory, which holds that a broad disinterest in social information underlies autism features. On the other hand, anecdotal reports from people with autism suggest that they find eye contact unpleasant. Studies that track eye movements as people view faces have provided support for both hypotheses.

The new work is elegant, scientists say. “Among the strengths is the conceptual clarity with which they framed the study, in pitting two hypotheses against one another,” says Jed Elison, assistant professor of child development at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, who was not involved in the work.

Gaze indifference:

The study, published 18 November in the American Journal of Psychiatry, is the first to address the issue in toddlers. This makes it more likely to get at the origins of altered gaze patterns in autism than previous studies, Jones says.

Jones’ team showed a series of videos to 38 typically developing toddlers, 26 toddlers being evaluated for autism, and 22 who showed developmental delays in cognition, language or movement, but did not meet criteria for autism. The children were all 2 years old. The researchers used eye-tracking technology to follow the children’s gaze as they watched the videos.

At first, the toddlers see a small blue-and-white circle flash on the screen as chimes sound to draw their attention. As soon as the child looks at the circle, a video of an actress appears in its place. The woman then speaks to the child in an engaging way.

In some cases, the circle’s location directs the child’s gaze to the actress’ eyes. At other times, the circle leads the child to look at another part of the actress’ face or the scene around her, which is set up to look like a child’s room, full of toys and colorful pictures.

When cued by the circle to look at the actress’ eyes, the toddlers with autism don’t look away from her eyes any sooner than the other groups do. This finding suggests that eye contact is not uncomfortable or unpleasant for them.

Conceptual clarity:

During the rest of the video, the typical toddlers tend to look at the actress’ eyes when her voice and facial expressions are emotionally engaging; they sometimes look elsewhere when she is not emotionally expressive.

Toddlers with autism spend less time looking at the actress’ eyes than typical toddlers do, but their eye contact doesn’t vary with the emotional content of her face.

“It’s a very clear and concise story,” says Frederick Shic, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Washington in Seattle, who was not involved in the work. “There’s not an aversive behavior that’s occurring. This is really gaze indifference.”

Children in the developmental delay group showed gaze patterns similar to those of the typical toddlers. “It really casts that difference of kids with autism into a stark light,” Jones says.

Larger studies are needed to sort out whether all toddlers with autism show this pattern of disinterest, scientists say. What’s more, adolescents and adults with autism often say eye contact is intense or unpleasant for them, so gaze aversion may develop later in life.

References:

- Moriuchi J.M. et al. Am. J. Psychiatry (2016) Epub ahead of print PubMed

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025