What does a genetic mosaic tell us?

New work suggests that the skin, a common source for deriving induced pluripotent stem cells, is a genetic mosaic. What does this mean for stem cell research? Are there implications for the human brain?

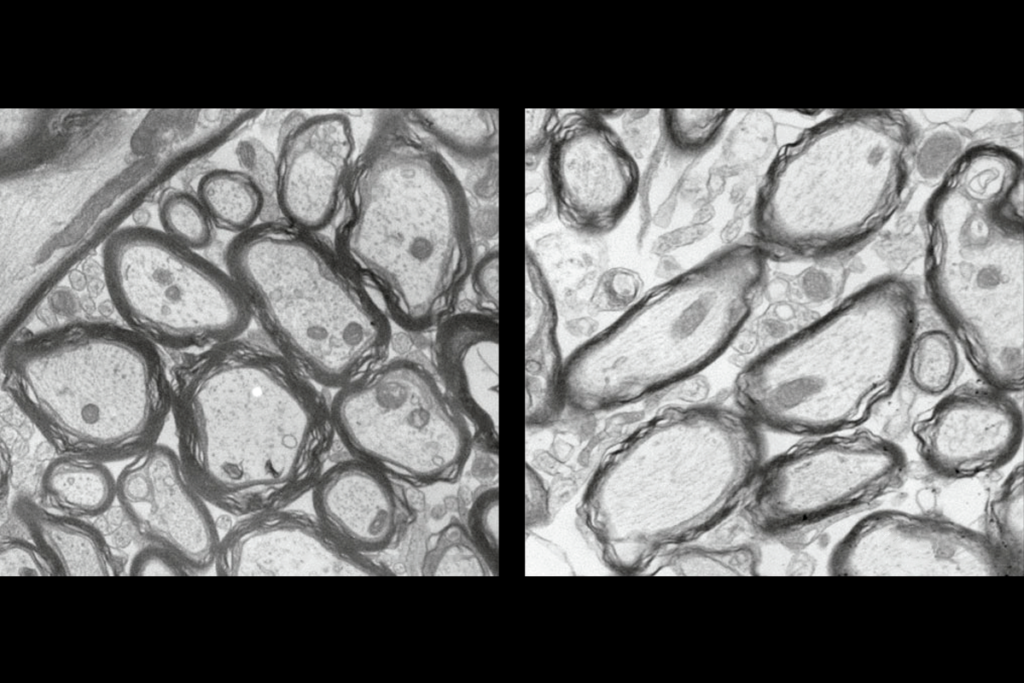

The process of deriving stem cells from fibroblasts does not introduce a lot of large mutations, according to a new analysis we covered last week.

Induced pluripotent stem, or iPS, cells are undifferentiated cells created by reprogramming adult skin cells. Because these cell lines carry the genome of the donor, they can be used to study disorders such as autism, or to screen therapies.

The new study found that at least half of the copy number variations — deletions or duplications of stretches of DNA — found in iPS cells derived from skin were present in the donor skin cells.

This finding eases some qualms about iPS cells, because it suggests the reprogramming process produces fewer mutations than had been suspected. But the fact that the skin cells themselves contain so many mutations raises a number of questions.

For example, lead investigator Flora Vaccarino says the findings suggest that iPS cells need to undergo more extensive genetic characterization. Others, however, question the wisdom of committing scarce financial resources to such an effort. We want to know what you think.

- Given the genetic variability in source cells, do we need to alter our approach to iPS cell research?

- Considering the high cost of sequencing iPS cell lines, how heavily should iPS cells be characterized?

- If genetic mosaicism is found to be common in the brain, what implications does it have for studying neurodevelopmnetal disorders?

Share your thoughts in the comments section below.

Recommended reading

The spectrum goes multidimensional in search of autism subtypes

Prosocial effects of oxytocin are state dependent; and more

Contested paper on vaccines, autism in rats retracted by journal

Explore more from The Transmitter

Deleting data or stopping its collection will erase years of valuable brain research