From genes to dynamics: Examining brain cell types in action may reveal the logic of brain function

Defining brain cell types is no longer a matter of classification alone, but of embedding their genetic identities within the dynamical organization of population activity.

In the past 10 years, neuroscientists’ capacity for characterizing cells has expanded dramatically; omics tools have enabled researchers to create entire cell atlases based on their transcriptomes, and high-volume recording tools make it possible to describe the functional properties of large populations of cells. Traditionally, these two facets of a cell’s identity remained largely separate—but that’s beginning to change.

Recent technological advances provide the tools to label and follow specific classes of brain cells while observing their coordinated activity during behavior. By combining large-scale recordings and genetic identification, researchers can now assign activity patterns to cell classes. These efforts reveal, for example, how defined neuronal populations help animals remember a route through a maze and how anatomically distinct neurons engage differently as animals switch between behavioral strategies.

As these recordings of multiple cells became possible, a central question emerged: What does it mean to define a cell type functionally?

When looking at populations of cells, a functional definition no longer refers to what a cell does in isolation but to how it participates in the population. Yet this collective view does not erase cell-type identity; rather, it places it in context. Functional organization emerges from how different cell types interact within population dynamics, and making sense of this organization requires approaches that preserve cell-type information while describing how activity evolves.

In this view, defining brain cell types is no longer a matter of classification alone but of embedding genetic identity within the dynamical organization of circuits that support cognition. Dissecting the contributions of distinct cell types and circuits to population activity is crucial for understanding how the brain constructs and transforms cognitive representations—and it’s already beginning to yield new insights.

F

The capacity for large-scale, simultaneous recordings has enabled researchers to look at how populations of cells encode information, including those with mixed selectivity. That has revealed that functional organization can arise in populations, even when individual neurons lack simple or stable tuning. For example, the way hippocampal place cells represent a specific environment can drift over time. Crucially, such drift at the level of individual neurons does not preclude stability at the population level; even when a single cell’s response properties change, the larger cell population can collectively encode the same information. Each of these views captures a different facet of circuit function. How, then, should a cell be defined functionally?

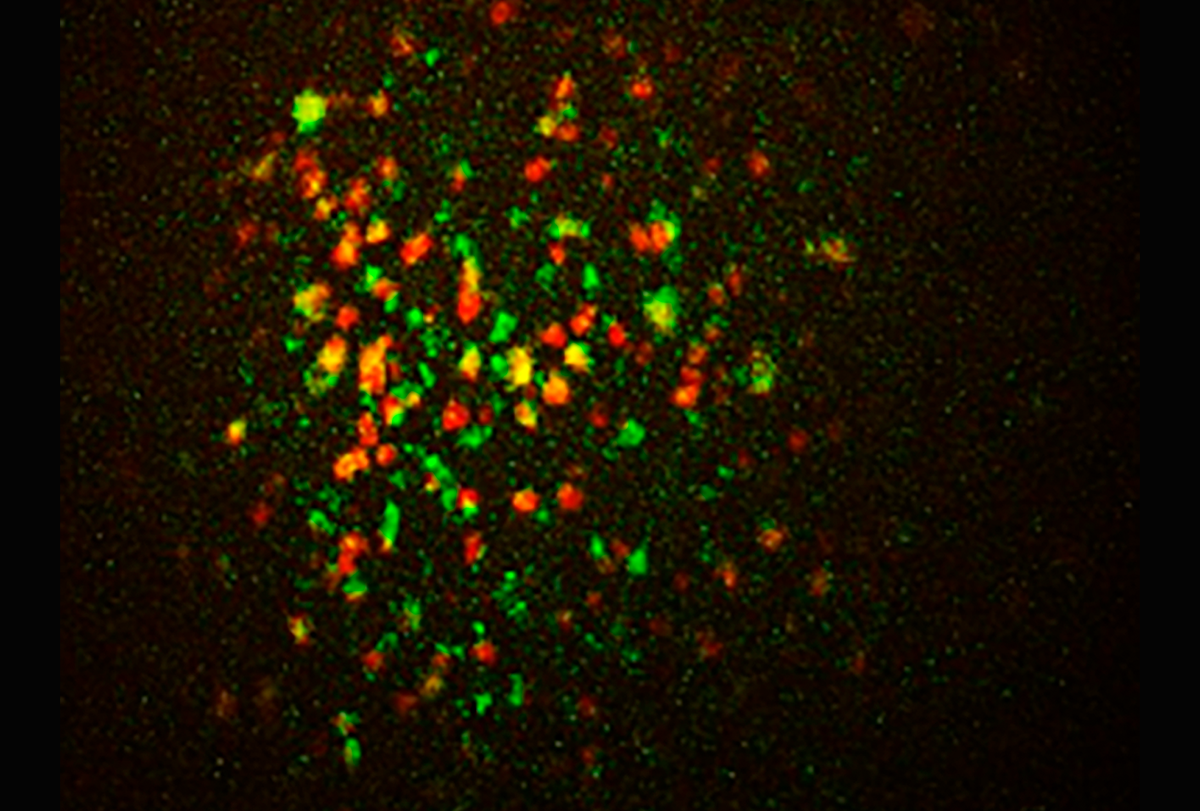

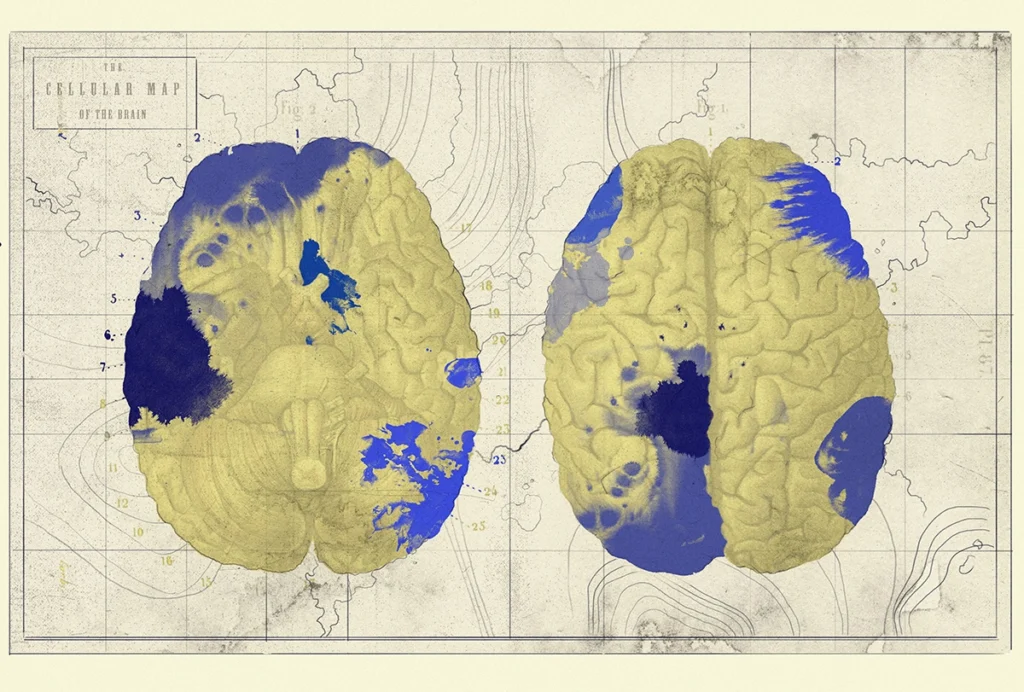

Genetically defined optical imaging further extends the observational scale and permits addressing this question directly. Cell-type-specific calcium imaging now makes it possible to monitor the activity of hundreds to thousands of neurons simultaneously, and mesoscopic approaches expand the field of view to cover large brain areas. This increase in scale shifts the emphasis from local circuits to distributed dynamics, revealing how genetically defined cell types and territories contribute to coherent brain activity.

As recordings scale up, they reveal new structure and challenge our intuitions. Patterns that are invisible at the level of individual cells emerge only when considering collective activity. Mathematical descriptions provide the necessary tools to reveal this structure, reducing complex population activity to shared trajectories and coordinated modes of variation. Much as the vast gene-expression space is reduced to lower-dimensional representations that organize cell types, population activity often organizes into simple geometrical forms such as lines, surfaces or clouds of points that reflect how information is represented.

I

Crucially, the structure that emerges depends on which cells are considered. Selecting genetically defined cell types offers a complementary view: Within the same ring-like topology, some populations rotate with internal representations, whereas others remain anchored to stable, global reference frames. This pattern suggests that different cell types contribute distinct computational roles: Some support flexible internal transformations, and others provide stable reference signals that anchor cognition to the external world.

Disentangling how distinct cell types contribute to population coding is crucial for understanding how the brain represents and transforms information. A cell-type-specific approach is also essential for targeted genetic manipulations, enabling increasingly precise control over the neural dynamics that support flexible cognition.

From bird flocks to neurons, emergent population codes remain elusive, in part because the collective structure cannot be inferred from any single element, nor is it captured by simple averaging. In neural circuits, genetically defined cell types rarely map onto fixed or isolated functional roles, making their population-level contributions strongly context dependent. Focusing on one element risks losing the collective structure, whereas averaging across the ensemble can obscure the diversity that drives changes. It is in the interplay between identity and dynamics that the logic of brain function may finally come into view.

AI use disclosure

Recommended reading

Knowledge graphs can help make sense of the flood of cell-type data

Where do cell states end and cell types begin?

Building a brain: How does it generate its exquisite diversity of cells?

Explore more from The Transmitter

Constellation of studies charts brain development, offers ‘dramatic revision’