In late February of this year, a few journalists emailed Peggy Mason asking for comment on “reviving-like” behavior in mice. A paper had just been published in Science describing a mouse approaching a familiar but unconscious mouse and performing a series of escalating actions upon it: grooming, biting its mouth and finally biting and pulling up on its tongue.

These actions, according to the paper, indicated prosocial behavior, in which one mouse was actively trying to benefit another. The journalists wanted to know what Mason thought of it.

“I’m sorry to say it, but it’s nonsensical,” says Mason, who years ago helped propel the rodent prosocial behavior field forward. The behavior seen in the work was real, she says, but she disputes the “interpretation of it,” despite studies published this year in Science Advances, Science and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that used a similar behavioral paradigm and concluded the actions were prosocial.

It is not unusual for Mason to be this assertive. She is “disputatious,” says Howard Fields, professor emeritus of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, who was Mason’s adviser for her postdoctoral fellowship. He adds that she sometimes carries her argument beyond what “is justified by the data.” Now, her opinionated nature is bumping up against a portion of the prosocial subfield that is not in line with her way of thinking.

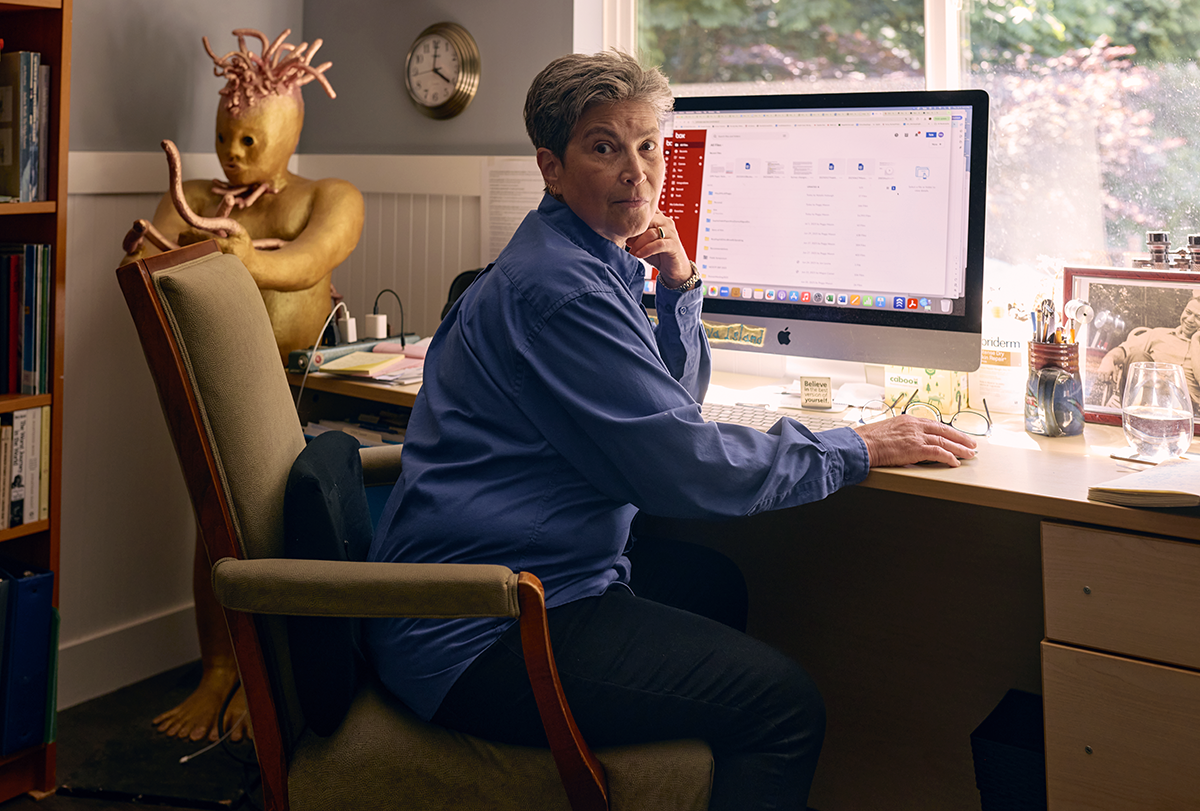

M

ason, professor of neurobiology at the University of Chicago, is currently on sabbatical in the Sunshine Coast region of British Columbia, Canada. She spends a portion of her days on her deck, which is decorated with wind chimes, mirrorballs and an electric-powered water fountain, and in the garden, tending to vegetables, herbs and flowers. She has a home office filled with books—including her own textbook, “Medical Neurobiology”—as well as family photos, a large art collection and framed pictures of all the cats she and her wife, artist Gisèle Perreault, have had over their nearly 40-year relationship.On her computer are two in-progress manuscripts concerning rat empathy and prosocial behavior research. Mason closed her rat lab in May. She has studied empathy and prosocial behavior in rats for about 17 years, but she mostly funded it through private foundation awards. She will still teach—David Zhu, a recent University of Chicago graduate in neuroscience, says Mason treated students “as her equal,” but never minded “interjecting” when she felt they were wrong—and in the fall she plans to run a neuroanatomy class for a study-abroad program in Paris. But she’s changing course from her rat research on helping and empathy.

The prosocial behavior field began in humans and then primates, long before Mason was around. Meredith P. Crawford’s 1937 experiment in chimpanzees helped define the field, showing that the animals demonstrate helping behavior. But the field really took off with the work of Frans de Waal, who showed, most notably in 1979, peacemaking behavior in chimpanzees.

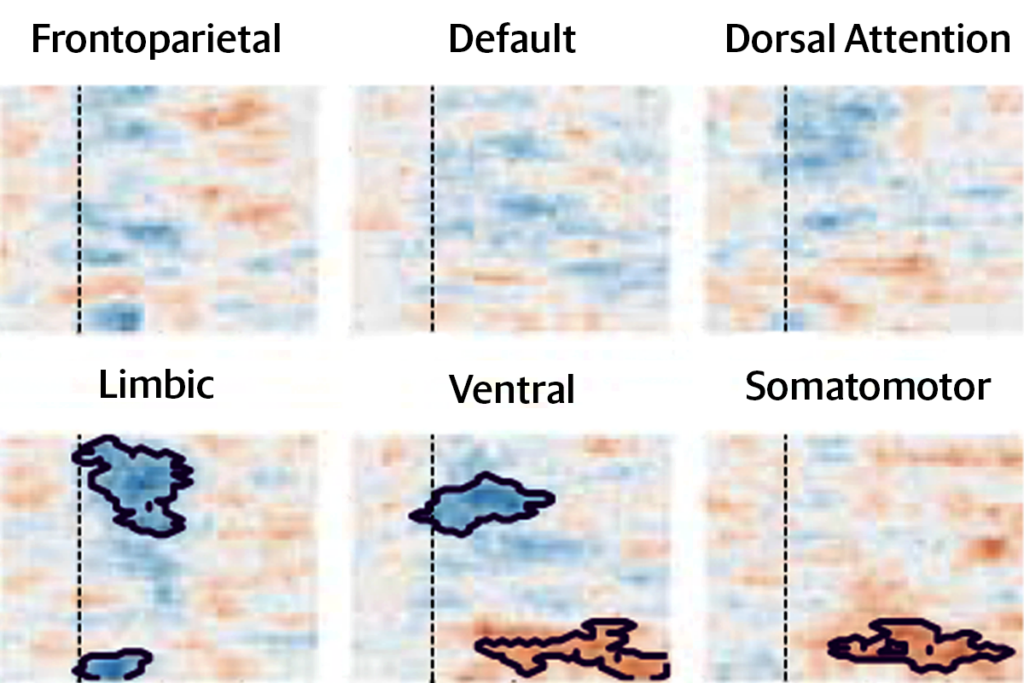

Russell Church started the rat prosocial behavior field in 1959, with contributions by George Rice and Priscilla Gainer in 1962, but it went mostly silent until 2006. That’s when Jeffrey Mogil and his colleagues published a paper in Science showing that in response to pain stimuli, mice are susceptible to “emotional contagion”—the spread of the same emotion across a social group.