‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

The atlas also offers up molecular and cellular targets for new pain therapies.

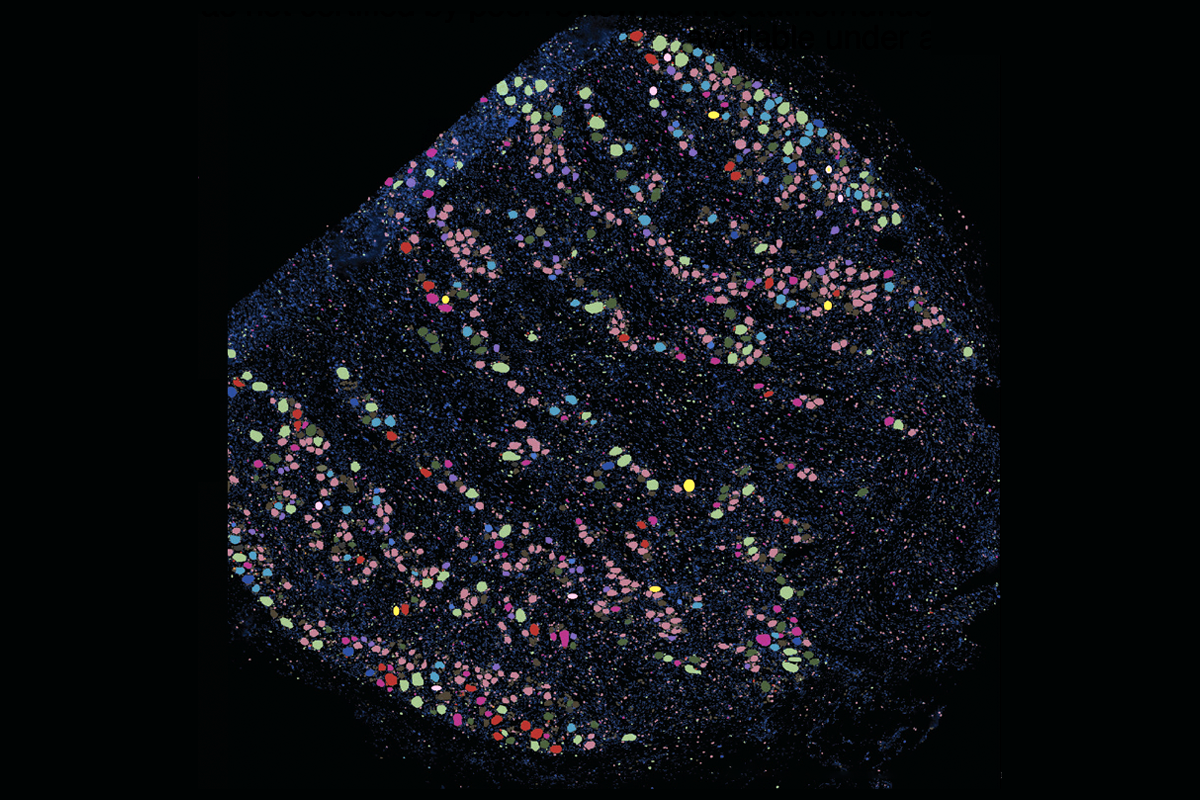

A new atlas of cells in the dorsal root ganglion details several novel types of sensory neurons and provides molecular and cellular targets for potential pain treatments. The atlas appeared as a preprint on bioRxiv last month; the data are also freely available online.

The dorsal root ganglia dangle off the spinal cord and house the cell bodies of the sensory neurons that enervate the entire body. “It’s a great tissue to study to come up with new targets to treat chronic pain,” as well as to understand how the nervous system processes touch, temperature and other somatosensations, says Theodore Price, one of the investigators on the project and professor of neuroscience at the University of Texas at Dallas.

But by virtue of their location, dorsal root ganglia are difficult to obtain. Researchers can’t order the samples they need and must instead rely on donations of varying quality collected in different ways from an array of people. “There’s a lot of uncertainty,” Price says.

To assemble the new atlas, a team consisting of Price’s lab and three others collected dorsal root ganglia over the course of two years during surgeries, autopsies and postmortem organ donations. The result contains more than 53,000 neurons and nearly 500,000 non-neuronal cells from 126 people spanning infancy to age 90.

“This is a real landmark study that really goes above and beyond in just sheer scale and number of samples to really get a very comprehensive view of what’s going on in the human sensory neurons,” says Diana Bautista, professor of cell and developmental biology at the University of California, Berkeley, who was not involved in the project. “This is unprecedented.”

T

“Finding new sensory neuron types for sensory biologists is not unlike finding new chemical elements for chemists,” says Allan-Hermann Pool, assistant professor of neuroscience and anesthesiology and pain management at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, who was not involved in the effort. “It’s truly fundamental, and it’s very important.”

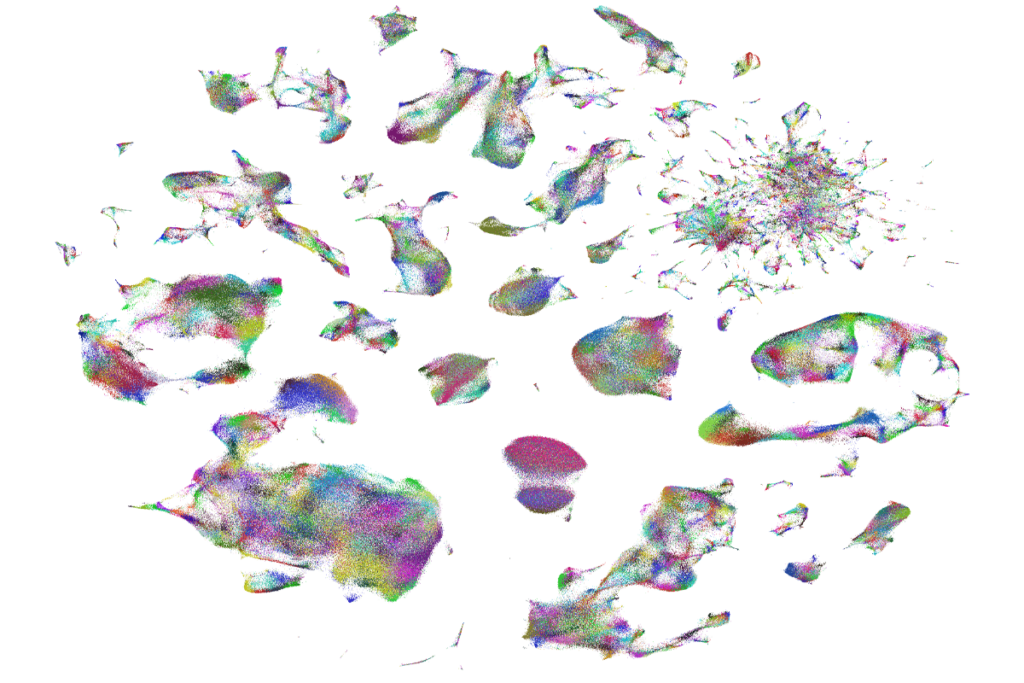

The methods each lab used to sequence the cells varied in the percentage of cells captured and sequencing depth, yet each landed on the same number of cell types.

This consistency among the teams, as well as with previous human and mouse atlases, “speaks to the fact that they were able to have some sort of robustness in this analysis, despite having to pull together a lot of very disparate datasets,” says Zack Lewis, senior scientist at the Allen Institute for Brain Science, who was not involved in the project. “It’s painting a pretty solid picture.”

R

The resource also illuminates cells and molecules implicated in pain processing in humans, which can be contrasted with those in mice both to identify “rational” targets for new pain therapies and to explain why past therapies failed to translate, Pool says.

The diversity of the donors makes it possible to ask questions about sex- and age-related differences, too. The proportion of most neuron subtypes is similar between men and women and across age, the atlas team reported in their preprint.

“The more donors you have, the more features you can start to look at,” says project investigator William Renthal, associate professor of neurology at Harvard University. The sheer number of donors in this atlas—nearly four times as many as in previous ones—“gives us a lot more confidence [in] where there are similarities and where there are differences.”

In future studies, Renthal says he hopes to examine how the medical histories of the donors—particularly those with pain disorders—correlate with gene expression in dorsal root ganglia.

T

But in the body, “cells don’t have names,” Renthal says. “Each cell is an individual; they all do their own thing.”

The atlas introduces a more detailed naming system that contains the fiber type, key genes that the neuron expresses and functional information—for example, A-Propr.HAPLN4 is an A-fiber proprioceptor neuron that expresses the HAPLN4 gene.

“Eventually, we can all be speaking the same language, not just about human DRG cell types, but comparing across different species too,” Lewis says. “That’s a nice effort and really does help to advance the field.”

Explore more from The Transmitter

Constellation of studies charts brain development, offers ‘dramatic revision’