Virtual public speaking assesses social attention in autism

To study attention in people with autism during complex social situations, researchers have developed a virtual reality version of public speaking, according to a study published 20 May in Autism Research.

To study attention in people with autism during complex social situations, researchers have developed a virtual reality version of public speaking, according to a study published 20 May in Autism Research1.

The computerized system allows researchers to repeat the experiment under the same conditions in different labs.

Preschool-aged children with autism often show deficits in joint attention, the ability to follow others’ focus. Unlike typically developing children, for example, children with autism may not look in the direction that a researcher is pointing. But there are few ways to study how older, high-functioning children continue to develop these skills.

The researchers designed the new system to study how 8- to 16-year-old children handle a situation that requires them to pay attention to themselves and others while also accomplishing a task.

In the virtual reality setup, the participants watch a monitor that shows seven avatars representing their peers. The researchers ask the participants personal questions and urge them to direct their answers to all of the avatars.

One avatar is directly in front of the participant, and others are seated farther away or to the side. The avatars all blink and nod to simulate interest. In some of the experiments, the avatars begin to fade until the participants look in their direction; in others they remain solid.

The participants wear headgear that allows the researchers to track which of the avatars they are looking at and for how long.

The 37 children with autism and 54 controls both paid better attention to the fading avatars than to those that remained solid. Both groups also looked more at the avatar in the center than at the others. The children with autism spent even less time looking at the avatars in the back and the sides than controls did, however.

The participants with autism who have symptoms of social anxiety or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, or have relatively low intelligence quotients, perform worse on the test than the other participants, the study found.

When the researchers replaced the avatars with spheres, all the participants spent less time looking at them than they had at the avatars. This suggests that children with autism don’t have an aversion to talking to people, the researchers say.

References:

1: Jarrold W. et al. Autism Res. Epub ahead of print (2013) PubMed

Recommended reading

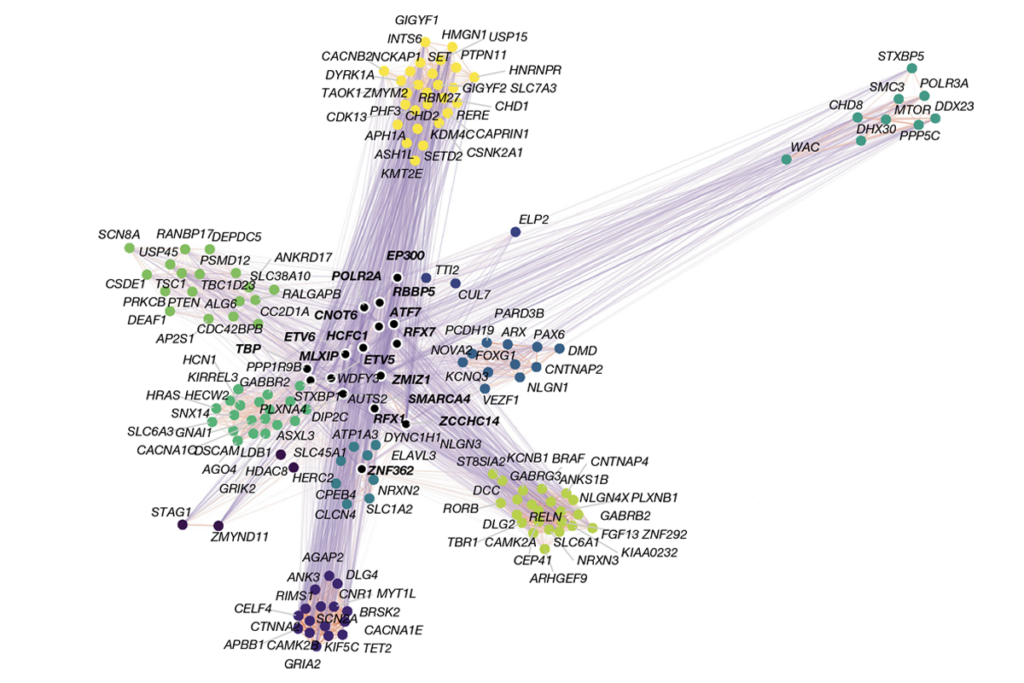

Organoid study reveals shared brain pathways across autism-linked variants

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

Explore more from The Transmitter

Frameshift: Raphe Bernier followed his heart out of academia, then made his way back again

Single gene sways caregiving circuits, behavior in male mice