Neuroscience needs single-synapse studies

Studying individual synapses has the potential to help neuroscientists develop new theories, better understand brain disorders and reevaluate 70 years of work on synaptic transmission plasticity.

Thousands of electrophysiological studies have shown that stimulating axons in precise patterns strengthens or weakens synaptic signaling—a phenomenon commonly known as synaptic plasticity. Neuroscientists have dissected the molecular mechanisms underlying synaptic plasticity, most often through perturbations of target proteins using pharmacological or genetic tools.

Most of these studies, however, use methods that record synaptic responses from large populations rather than from individual synapses. Such approaches include field recordings, in which electrodes detect the activity of hundreds or thousands of synapses on nearby neurons, and whole-cell recordings, which rely on attaching an electrode to the soma to record activity arising from the populations of synapses converging onto that one neuron.

The problem is that the interpretation of results from such studies—and the construction of influential theories from them—has relied on an assumption that turns out to be incorrect: namely, that the excitatory synapses being studied all have the same molecular and physiological properties. I have worked on these problems since 1989, initially as a postdoctoral fellow with Eric Kandel, and until just a few years ago, I—like others in the field—assumed that excitatory synapses in the mammalian brain were more or less uniform.

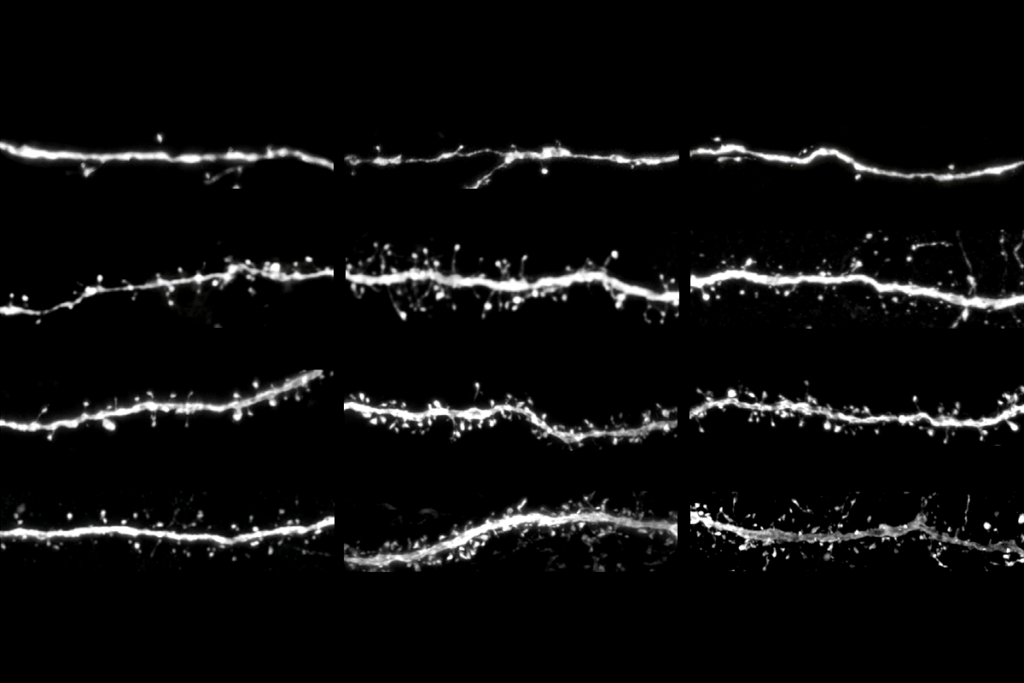

But thanks to the advances in synapse proteomics and synaptomics, we now know those assumptions were wrong. Newer research has revealed that synapses vary in a wide range of molecular properties, including protein levels; splicing and post-translational modifications; the assembly of proteins into complexes that form subsynaptic architecture; and the rates at which these proteins and higher-order structures are replaced. The complement of molecularly diverse synapses in the brain is now known as a synaptome. These diverse synapses are differentially distributed between neuronal types and even within the dendritic tree of a single neuron, forming a synaptome architecture. Every brain region has a distinctive synaptome architecture, which changes throughout the lifespan.

This clear view of synaptic diversity shows that proteins with major functional roles vary significantly from one synapse to another. For example, many excitatory synapses lack the NMDA receptor, long considered a cornerstone molecule in studies of long-term synaptic plasticity. What forms of plasticity do these synapses exhibit? How can we meaningfully interpret historical studies performed on populations of diverse synapses? To answer these questions, we need to better understand the physiological and molecular properties of single synapses and develop tools to study them at this resolution.

W

For example, in my lab, we propose that synapse diversity is a mechanism for encoding both innate and learned information and provides a parsimonious mechanism for recall. Simply put, each molecular variety of synapse responds differentially to patterns of neural activity, producing characteristic changes in the amplitude of postsynaptic currents in response to each incoming pulse of neurotransmitter.

Imagine a synapse with molecular composition X and another with molecular composition Y that respond differently to trains of action potentials such that X responds more strongly at 1 hertz and Y at 5 hertz. The distribution of X and Y synapses on neurons would determine the frequency that drives neuronal firing—a simple recall mechanism. Learning could change the number of X and Y synapses and thereby encode memories without any alteration in basal synaptic strength, challenging a core tenet of current learning models. Another exciting possibility arising from the discovery that synapses have different rates of protein turnover is that synapses with slow protein turnover may store long-term memories, and those with rapid turnover may store short-term memories.

Synapse molecular diversity also provides new explanations for the evolution of the brain and for species differences. For example, differential expression of duplicated genes generates synapse diversity, and many of these differences are species-specific, as evidenced by the additional genome duplications and their effects on synapse proteome complexity in zebrafish. Moreover, experimental studies support the idea that synapse proteome complexity and synaptome diversity drove an increase in behavioral complexity among vertebrates.

A better understanding of synaptic diversity and the role that specific molecules play could also have important implications for treating brain disorders. Nearly 1,000 synaptic genes implicated in human brain disorders are differentially expressed, resulting in distinct synaptic pathologies in subsets of synapses at different brain locations and ages. An emerging view is that each brain disorder is characterized by a distinct signature of vulnerable synapse types. Detailed interrogation of the molecular and physiological properties of these synapses may identify therapeutic strategies to restore or replenish them.

There is a pressing need to integrate single-synapse physiology and proteomics to unravel the functional importance of the extraordinary synaptome architecture of the brain. This integration is not straightforward using existing technology. The most feasible approach to recording presynaptic and postsynaptic electrical responses is likely to be voltage-sensitive optical recording. My colleagues who are developing such tools tell me that we are on the brink of having sensors that are fast and sensitive enough for single-synapse studies. At the same time, we must determine the molecular parameters of the synapses that are being recorded. Currently, it is possible to classify types and subtypes of excitatory synapses using small numbers of fluorescently labeled proteins. But to truly define molecular composition at the single synapse level, we would need to increase the depth of proteome detection to dozens or hundreds of proteins. This level of precision remains a dream, for now.

Single-synapse studies would enable the field to revisit studies of synaptic transmission and plasticity from the past 70 years at single-synapse resolution. There is every prospect that transformative theories of brain and behavior will emerge, along with entirely new approaches to treating disorders caused by synapse pathology.

Recommended reading

Securing the academic pipeline amid uncertain U.S. funding climate

Let’s teach neuroscientists how to be thoughtful and fair reviewers

Lack of reviewers threatens robustness of neuroscience literature

Explore more from The Transmitter

Protein tug-of-war controls pace of synaptic development, sets human brains apart