Enriched environment staves off autism-like behavior in rats

Rats exposed in utero to the epilepsy drug valproic acid, a risk factor for autism, do not develop autism-like behaviors if they are reared in a stimulating environment. Researchers presented the unpublished findings yesterday at the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

Rats exposed in utero to the epilepsy drug valproic acid (VPA), a risk factor for autism, do not develop autism-like behaviors if they are reared in a stimulating environment. Researchers presented the unpublished findings yesterday at the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

Creating a stimulating environment is not sufficient, however. It must also be constant and unchanging.

The work suggests that people with autism would benefit from a highly predictable environment, says Monica Favre, a postdoctoral fellow in Henry Markram’s lab at École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in France who presented the findings. “Environmental stimulation needs to be highly predictable and familiar, but it needs to be tailored to each individual’s particular hypersensitivity.”

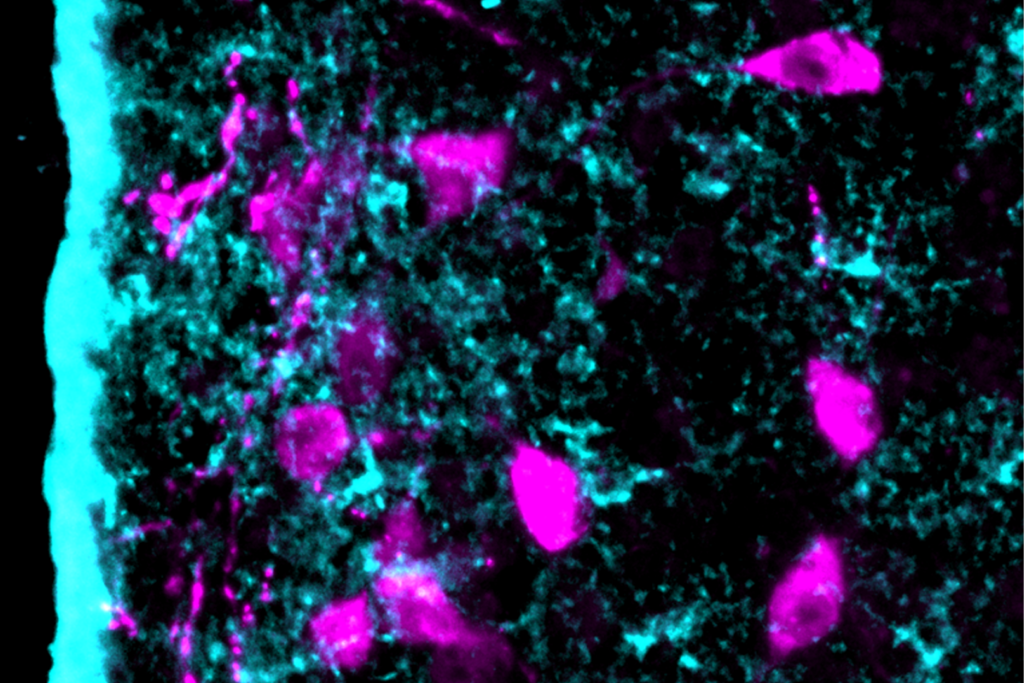

Prenatal exposure to VPA is known to trigger autism-like features in rats, such as repetitive behaviors and impaired social interactions. Certain brain regions in exposed pups tend to be overly connected and hyperreactive to stimuli1, 2.

These findings inspired the controversial ‘intense world theory,’ which suggests that super-charged brain circuits in people with autism make certain stimuli painfully intense, hindering social interactions and learning opportunities. Consistent with this idea are reports that people with autism tend to be oversensitive to loud noises and bright lights.

In the new study, researchers injected pregnant rats with VPA and reared the pups in one of three environments, with 18 rats per group.

One group grew up in a standard lab cage. The second group was raised in an enriched environment, complete with toys, hiding places, odors and other rats. This environment was unpredictable, meaning that the researchers changed the toys, sights, sounds and smells the animals experienced twice per week.

The third group also grew up in an enriched environment, but a predictable one in which the stimuli remained unchanged.

Beginning 83 days after the rats were born, the researchers assessed their performance on a wide variety of behavioral tests. They found that the VPA-exposed rats raised in either the standard or unpredictable environments were more anxious, less social and did not learn as well as controls did. This is consistent with results from similar studies.

By contrast, VPA-exposed rats raised in the predictable enriched environment performed better than other VPA-exposed rats on all these tasks. “It’s not stimulation in the environment per se that is important,” says Favre. “It’s predictable stimulation in the environment that is taming down the hyperfunctionality.”

Strangely, however, controls housed in the predictable environment performed worse than the VPA-exposed animals. Favre says she doesn’t know what to make of the results, but speculates that the brains of the controls are simply different from those of the VPA-exposed animals, and react to the world differently.

For more reports from the 2014 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

References:

1. Markram K. et al. Neuropharmacology 33, 901-912 (2008) PubMed

2. Silva G.T. et al. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 1, 1-9 (2009) PubMed

Recommended reading

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Securing the academic pipeline amid uncertain U.S. funding climate

Let’s teach neuroscientists how to be thoughtful and fair reviewers