People with autism can read emotions, feel empathy

The notion that people with autism lack empathy and cannot recognize other people’s feelings is wrong.

There is a persistent stereotype that people with autism are individuals who lack empathy and cannot understand emotion. It’s true that many people with autism don’t show emotion in ways that people without the condition would recognize1.

But the notion that people with autism generally lack empathy and cannot recognize feelings is wrong. Holding such a view can distort our perception of these individuals and possibly delay effective treatments.

We became skeptical of this notion several years ago. In the course of our studies of social and emotional skills, some of our research volunteers with autism and their families mentioned to us that people with autism do display empathy.

Many of these individuals said they experience typical, or even excessive, empathy at times. One of our volunteers, for example, described in detail his intense empathic reaction to his sister’s distress at a family funeral.

Yet some of our volunteers with autism agreed that emotions and empathy are difficult for them. We were not willing to brush off this discrepancy with the ever-ready explanation that people with autism differ from one another. We wanted to explain the difference, rather than just recognize it.

So we looked into the overlap between autism and alexithymia, a condition defined by a difficulty understanding and identifying one’s own emotions. People with high levels of alexithymia (which we assess with questionnaires) might suspect they are experiencing an emotion, but are unsure which emotion it is. They could be sad, angry, anxious or maybe just overheated. About 10 percent of the population at large — and about 50 percent of people with autism — has alexithymia2.

Ignorance of anger:

It’s tempting to think that having autism somehow causes alexithymia, but it’s worth remembering that you can have autism without alexithymia and vice versa. Also, even though there are higher rates of alexithymia in people with autism, there are equally high rates in people with eating disorders, depression, substance abuse, schizophrenia and many other psychiatric and neurological conditions.

So can alexithymia explain why some individuals with autism have difficulties with emotions and some don’t? Perhaps it is alexithymia, not autism, that caused the emotional difficulties we heard about from some of our participants, the difficulties that people often assume happen in everybody with autism.

To find out, we measured empathy for another’s pain in four groups of people: individuals with autism and alexithymia; individuals with autism but not alexithymia; individuals with alexithymia but not autism; and individuals with neither autism nor alexithymia3.

We found that individuals with autism but not alexithymia show typical levels of empathy, whereas people with alexithymia (regardless of whether they have autism) are less empathic. So autism is not associated with a lack of empathy, but alexithymia is.

People with alexithymia may still care about others’ feelings, however. The inability to recognize and understand anger might make it difficult to respond empathically to anger specifically. But alexithymic individuals know that anger is a negative state and are affected by others being in this state. In fact, in a separate test we conducted last year, people with alexithymia showed more distress in response to witnessing others’ pain than did individuals without alexithymia4.

Facing feelings:

Autism is associated with other emotional difficulties, such as recognizing another person’s emotions. Although this trait is almost universally accepted as being part of autism, there’s little scientific evidence to back up this notion.

In 2013, we tested the ability of people with alexithymia, autism, both conditions or neither to recognize emotions from facial expressions. Again, we found that alexithymia is associated with problems in emotion recognition, but autism is not5. In a 2012 study, researchers at Goldsmiths, University of London found exactly the same results when they tested emotion recognition using voices rather than faces6.

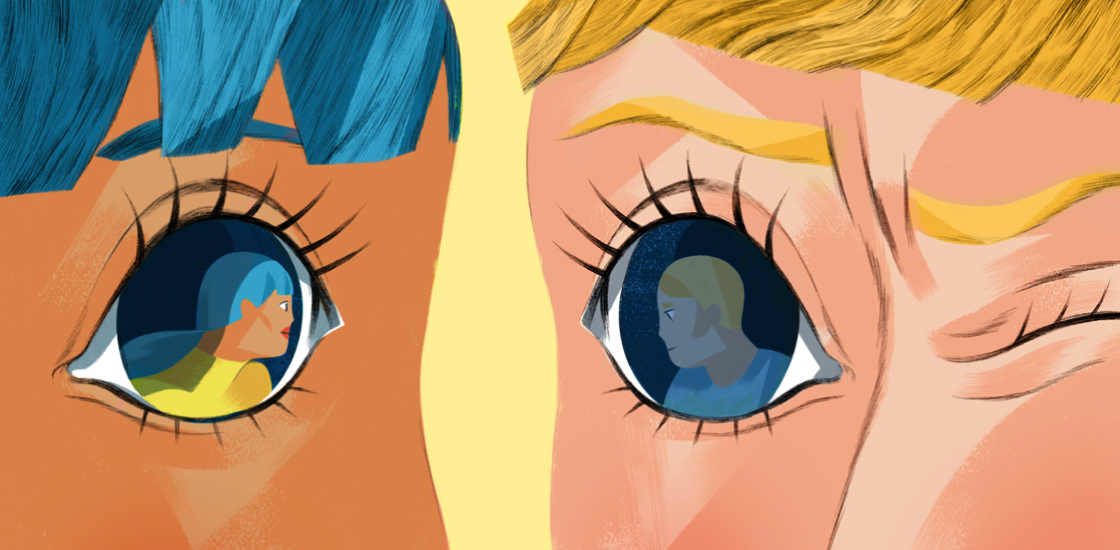

Recognizing an emotion in a face depends in part on information from the eyes and mouth. People with autism often avoid looking into other people’s eyes, which could contribute to their difficulty detecting emotions.

But again, we wanted to know: Which is driving gaze avoidance — autism or alexithymia? We showed movies to the same four groups described above and used eye-tracking technology to determine what each person was looking at in the movie.

We found that people with autism, whether with or without alexithymia, spend less time looking at faces than do people without autism. But when individuals who have autism but not alexithymia look at faces, they scan the eyes and mouth in a pattern similar to those without autism.

By contrast, people with alexithymia, regardless of their autism status, look at faces for a typical amount of time, but show altered patterns of scanning the eyes and mouth. This altered pattern might underlie their difficulties with emotion recognition7. (People who have autism or alexithymia and would like to participate in our studies can click here for details.)

Emotional rescue:

We think these results, and the others we have found since, disprove the theory that autism impairs emotion recognition8,9. If people assume that someone with autism lacks empathy, they will be wrong about half the time (because only half of individuals with autism have alexithymia). Making this assumption is unfair and can be hurtful.

What’s more, our work demonstrates that we urgently need tools to help individuals who have both autism and alexithymia understand their own and other people’s emotions. Meanwhile, people with autism who don’t have alexithymia might focus on building on their emotional strengths to mitigate the social difficulties associated with the condition.

At the same time, alexithymia doesn’t preclude acting in a prosocial and moral fashion. Indeed, one of our studies shows exactly this in individuals with autism9. Although people who have alexithymia but not autism find it acceptable to say hurtful things to others, people who have both autism and alexithymia do not. We think people with autism use other information (such as social rules) to decide whether what they say will be hurtful, rather than relying on their understanding of emotions.

We recommend that researchers test some of the basic assumptions about the capabilities of people with autism. Importantly, they should try to separate the impact of autism from that of conditions such as alexithymia that frequently accompany it10.

References:

- Brewer R. et al. Autism Res. 9, 262-271 (2016) PubMed

- Berthoz S. and E.L. Hill Eur. Psychiatry 20, 291-298 (2005) PubMed

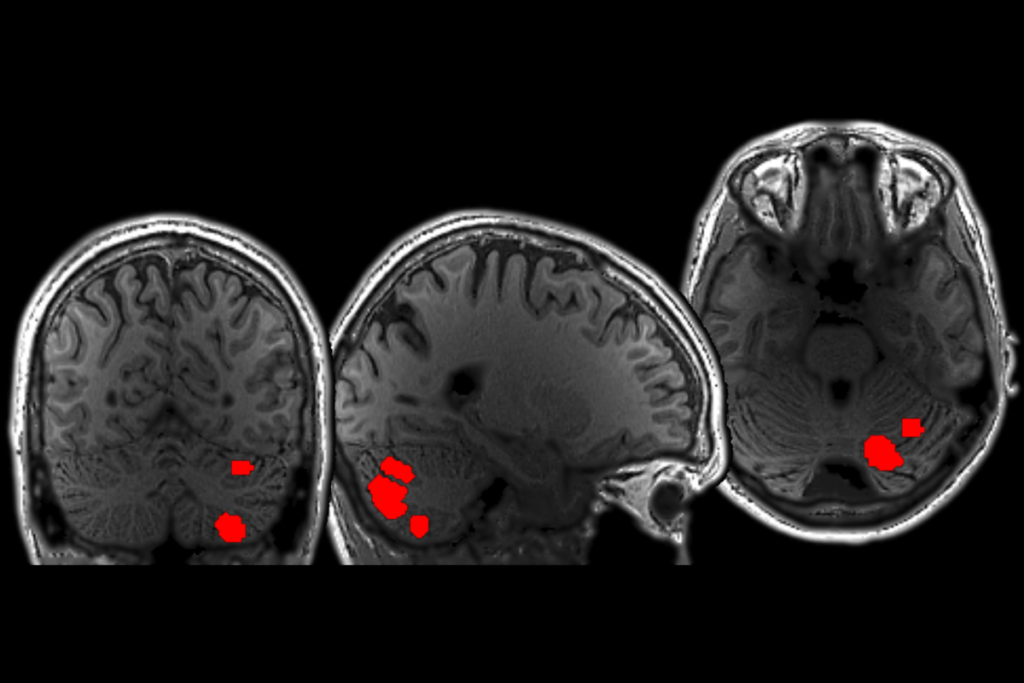

- Bird G. et al. Brain 133, 1515-1525 (2010) PubMed

- Brewer R. et al. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 124, 589-595 (2015) PubMed

- Cook R. et al. Psychol. Sci. 24, 723-732 (2013) PubMed

- Heaton P. et al. Psychol. Med. 42, 2453-2459 (2012) PubMed

- Bird G. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 41, 1556-1564 (2011) PubMed

- Oakley B.F.M. et al. J. Abnorm. Psychol. In press

- Brewer R et al. J. Affect. Disord. Under review

- Cook J.L. et al. Brain 136, 2816-2824 (2013) PubMed

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

Explore more from The Transmitter

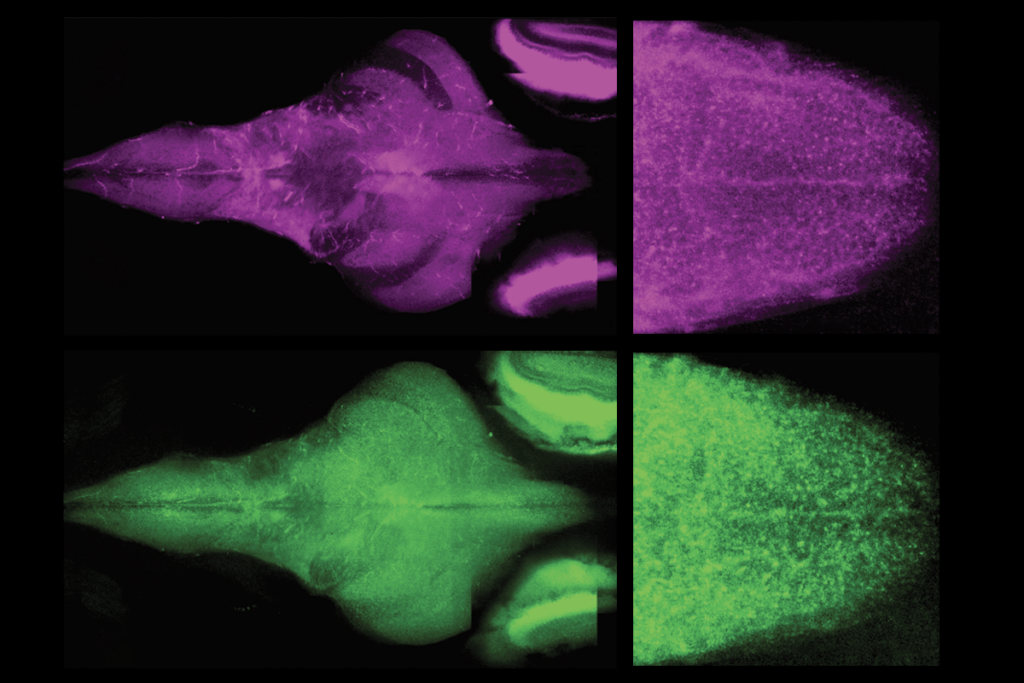

Cerebellum responds to language like cortical areas

Neuro’s ark: Understanding fast foraging with star-nosed moles