Exclusive: Recruitment issues jeopardize ambitious plan for human brain atlas

A lack of six new brain donors may stop the project from meeting its goal to pair molecular and cellular data with the functional organization of the cortex.

At least six new brain donors who can do a functional MRI scan—that’s what it will take to complete the most comprehensive human brain atlas yet, project investigators say. The Human and Mammalian Brain Atlas (HMBA) aims to capture information about the identity and location of cells across the entire brain and tie it, for the first time, to the functional organization of the cortex.

The atlas, one of several projects in the BRAIN Initiative Cell Atlas Network funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, stands to be “a quantum jump in the quality of the data and the resolution that we can analyze it,” says David Van Essen, professor of neuroscience at Washington University in St. Louis and an HMBA investigator.

The first atlas, published by the Allen Institute in 2011, contains gene expression information across the brain projected onto an MRI reference space. “By today’s standards, that’s really low-resolution information,” but it’s still “used like crazy,” says Ed Lein, co-creator of the first atlas and one of the lead investigators of the HMBA project at the Allen Institute for Brain Science.

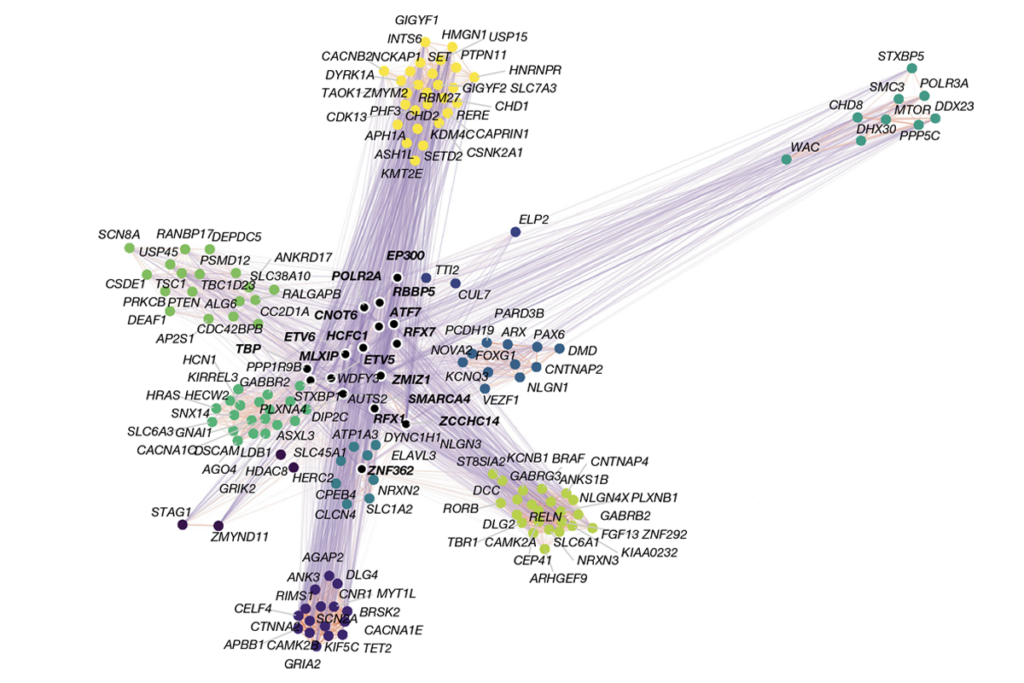

Subsequent iterations mapped more of the human brain’s cellular and molecular landscape and at higher resolution. A “first draft” cell atlas, Lein says, published in a trove of papers in 2023, employed single-cell sequencing techniques to catalog thousands of cell types in the human brain.

But as “exceptional” as these resources are, their utility is limited by a lack of functional information about the brain regions, says Avram Holmes, associate professor of psychiatry at Rutgers University, who is not involved with the project.

So for HMBA, “we wanted to connect the dots” and include the unique functional organization of each donor’s brain, Lein says. But after two years of outreach, only two participants out of the six necessary to capture individual variability have volunteered—and the grant is slated to end in three years, if it runs its full course.

“We’re sort of running out of ideas.” says HMBA collaborator Dirk Keene, Nancy and Buster Alvord Endowed Chair in Neuropathology at the University of Washington School of Medicine. “Honestly, I’m open to any suggestions.”

T

he new atlas—informed by fMRI scans of individual donors, taken while they are still alive—“would be a unique resource that is not currently available in the field,” Holmes says.Each hemisphere’s cortical sheet is roughly the size of a 13-inch pizza, “crumpled to squeeze them inside the skull,” Van Essen says. Because that folding differs from person to person, researchers cannot pinpoint functionally distinct regions and networks from structural information alone. This is particularly true for areas that contribute to higher cognitive functions, Van Essen says, such as the fusiform face area, which is involved in recognizing faces.

Yet when neuroimaging researchers previously mapped a participant’s fMRI data onto the structure of an atlas donor’s brain, they had to assume that the two brains were functionally organized in the same way, says Elvisha Dhamala, assistant professor of psychiatry at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research, who is not involved in the project. With the HMBA, however, researchers would be able to match brain areas according to their function, she adds.

“Having that structural and functional data within the same participants would be extremely important,” Dhamala says. “We can get a much more comprehensive picture of how structure and function are linked, and then how those are then related to the genetic, the cellular, the molecular components.”

T

he HMBA team needed a new approach to find prospective brain donors, Lein says. Given the project’s aims, several factors limit eligibility: Participants must have a terminal condition unrelated to the brain and no neurological disorders, live within a three-hour drive of Seattle and be well enough to complete a 30-minute fMRI scan.Initially, Lein and Keene planned to recruit volunteers in hospice care. Instead of approaching potential donors directly, which they worried would seem coercive, they asked hospice care workers to share the opportunity with their patients. But no volunteers came forward, says study collaborator Wayne McCormick, professor of medicine and division head of geriatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine. McCormick spent about one year contacting hundreds of hospice workers in the Seattle area, many of whom were “enthusiastic” but wouldn’t mention the study unless a patient expressed a desire to participate in research.

After the one-year mark, the team expanded their outreach to palliative care clinicians, oncologists and death doulas, and ran a local ad campaign, Keene says.

The most fruitful route seems to be when a clinician is excited about the project and shares it with their patients. The two participants who have volunteered since the team launched its outreach effort were both referred by the same oncologist within a two-month period, Keene says; the doctor has since moved to a city outside the geographical limits of the study.

“We feel like we just haven’t hit the ‘golden referrer’ yet,” McCormick says.

Meanwhile, work to create similar atlases for adult marmoset and macaque brains is well underway, Lein says. And as a backup, the team also has six brains previously donated by three women and three men that they plan to use to create whole-brain cell atlases, just without the functional information for the cortex. They knew recruiting people who could do an fMRI scan before donating their brain would be the hardest part of the project, he adds. “We set it up so that if it failed, we still had a very robust project. It wasn’t, like, completely mission critical, but it would be much better if we could do it.”

Lein, Keene and McCormick say they are still hopeful that the functional component of HMBA will pan out, but they also are eyeing the time left on their funding. “NIH grants have time frames,” Lein says, “and eventually, if we’re not successful, we’ll have to make some choices.”

Recommended reading

Organoid study reveals shared brain pathways across autism-linked variants

Single gene sways caregiving circuits, behavior in male mice

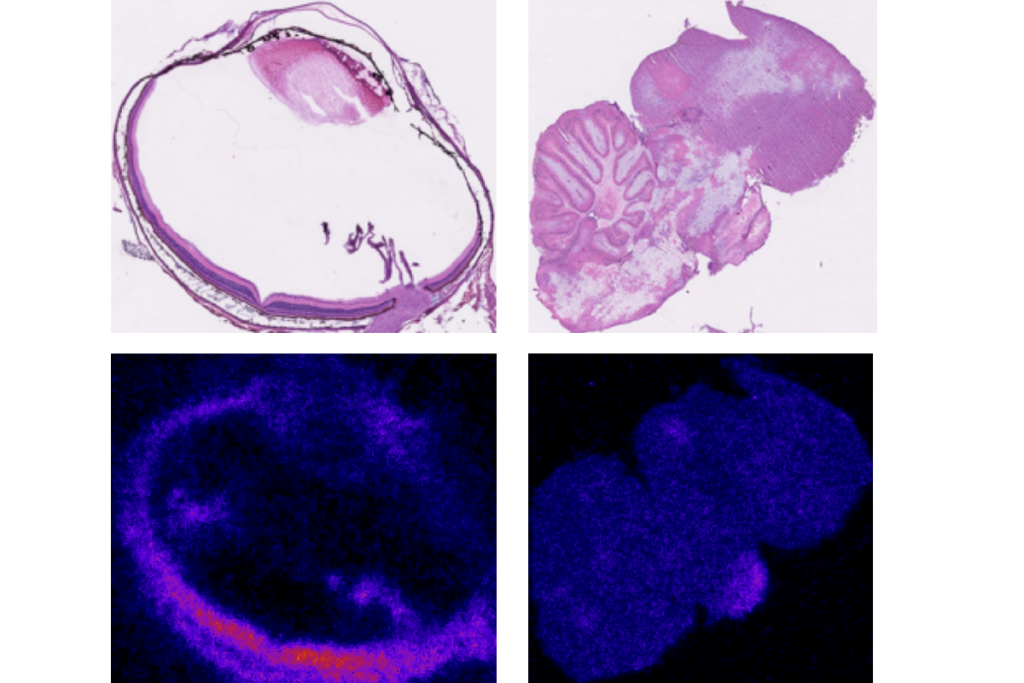

Inner retina of birds powers sight sans oxygen

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuroscientists reeling from past cuts advocate for more BRAIN Initiative funding

Grace Hwang and Joe Monaco discuss the future of NeuroAI